They thought that things would never be the same again. And who could blame them, gazing up from their encampments in the heart of over a thousand cities across five continents.

The world had never seen anything like this. They had never felt anything like this. Dreamers flooded in from the forgotten corners, gathered among the sympathy of strangers to remember the humanity that had been lost beneath the debris of contemporary life.

Ladling soup, surrounded by the yellowed pages of the library yurts, they imagined a future in which consumption makes way for connection, in which the belief in universal human worth and potential could be the seed of a new social contract. The parks and squares were their laboratories; their visions transposed from the haloed tomorrow into the dirt and flesh of the here and now.

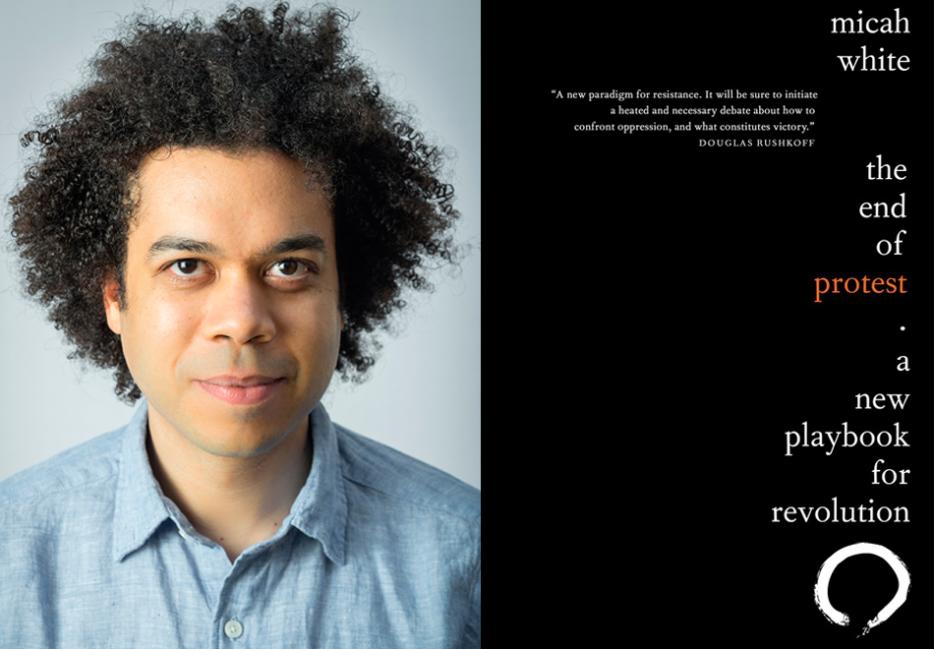

Five years later, the legacy of Occupy Wall Street is a fertile, if disputed, terrain: of disenchantment, of determination—and in the view of activist and author Micah White, of difficult lessons still being learned. As the former editor of Canadian anticonsumerist magazine Adbusters, White, along with magazine cofounder Kalle Lasn, was one of the co-originators of the #OCCUPYWALLSTREET meme that launched the movement on September 17 in New York, unleashing a chain reaction that would spread to 82 countries around the world.

In The End of Protest : A New Playbook for Revolution, White delivers a forceful call for the world’s activists and idealists to reimagine protest for the 21st century. Infused throughout with a sense of hope and possibility, the book offers an important and insightful account of Occupy’s successes and failures, a compelling projection into alternative futures, and above all, an impassioned plea to revive the revolutionary imaginary.

I spoke with Micah in Montreal.

Shawn Katz: So, “The End of Protest.” It’s a pretty evocative title. What were you hoping to convey?

Micah White: The “end of protest” doesn’t mean the absence of protest, but the proliferation of ineffective protest. What I’m trying to get across is that we live in this time with the most frequent protests in human history, the largest protests in human history, and yet they’re not working. So it’s kind of a provocation to activists to take a step back, and question this phenomenon.

Yet despite that, you also write that “the ingredients for global revolution are now here.” What makes you say that?

I think we’re still living under the revolutionary shadow that inspired the Arab Spring, that inspired Occupy Wall Street. People are still just as desperate for social change, and at the same time, I think that we have this beautiful capacity now to see movements emerge around the world, and if any new tactic were to come up in any of them, we can import them into our countries immediately.

The economic situation that created Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring is still there, but what triggered Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring was activists doing new behaviours. Those movements didn’t look like anything that we’d seen before.

You mention the Arab Spring, and a lot of the book is about Occupy Wall Street. In 2012, there was a similar movement in Montreal which was bigger than anything we’d ever seen in our history, and for a few months there was that “revolutionary moment” where suddenly everything seemed possible.

Yeah, it wasn’t just America, not just Montreal, but Brazil had the same thing.

Turkey too.

Yeah, all these different countries experienced the same thing, which is the sudden emergence of a social movement that people actually believed was going to create revolutionary change. And that’s the crucial thing, that people really believed it. So we need to understand why that happened.

Getting back to the premise of your book, that protest is essentially broken, you invoke Occupy as a textbook example of a movement that should have succeeded, and yet didn’t. Tell us what you learned from what you call the “constructive failure” of Occupy Wall Street.

Occupy Wall Street wasn’t a total failure. It did create positive things, changed the discourse. But our movement failed to achieve the objective, which was to get money out of politics. So that’s why I call it a constructive failure. In failing, it taught us a very important point: basically, that activists have been chasing an illusion. We’ve been acting as if the only thing you need to do to create social change is to get millions of people into the streets, largely non-violent, rallying around the same kind of message, which we saw in Montreal and Brazil. Activists have been trying to create these mass spectacles.

They’re extremely difficult to achieve, and you can even waste a decade trying to do it. But then when you finally do it, you have to realize, “Oh, it didn’t work.” So there’s no reason to continue to follow that storyline.

This is the book’s main argument really, that protest should not stick to the script of what worked in the past, but should always try to innovate and break the mould. And of course part of this is that tactics only ever work the first time they’re tried. But there’s also a deeper way in which shattering routines, shattering conventions, can open up this breach in the status quo that can spark a revolutionary moment. I was wondering if you could explain this relation a little more.

One way of looking at it is that revolution is one of the ways humans break their patterns and inaugurate new eras of human history, and we’ve seen this [going] back to the dawn of human civilization. We actually have papyrus from ancient Egypt five thousand years ago that talks about people overthrowing the king. So periodically throughout history, revolutions occur, and they serve a necessary purpose and function in human society.

The core thing to realize—and this is something that activists need to understand, I think—is that people join social movements that they believe are going to win. They don’t join social movements that are just the biggest. A lot of activists have been trying to create the biggest social movement or the strongest movement. But instead, what people are craving is a kind of loss of fear, a collective awakening, a kind of mood of what it feels like to be among this group of people, and to fully believe that you’re in the midst of this revolutionary moment.

I feel that what scares a lot of people away from protests is the confrontational element, especially with police. What was perhaps so successful about Occupy—and to some extent with the Maple Spring movement here—was that there was a hopeful, communal aspect that tapped into something people were thirsting for. It made protest a joyous thing as opposed to an angry thing. Do you think that’s an important part of protest?

I do. I think the core thing is that social movements spread through a contagious mood and a new tactic, and that contagious mood is a mood of losing one’s fear. That’s why the Arab Spring was inspired by a Tunisian fruit seller who set himself on fire. He unleashed this kind of collective fearlessness—like “Wow, that guy just killed himself to protest, surely I can risk arrest.” So on the one hand, that carnivalesque mood is important, the feeling of joy is important.

But on the other hand, I think that’s not really enough. We can’t just lose our fear. We also have to start to think concretely about, what is our strategy for actually gaining power? You can see that in 2011, the global movement wasn’t ready to think about that. The secular youth of Egypt who overthrew Mubarak weren’t ready to run for elections. In Spain they weren’t ready to engage in elections. I think we’re seeing now that people are starting to understand, it needs to be a one-two blow: We use protest to topple a regime, but then you have to be willing to step in. Otherwise we’re just giving power to people who sometimes are worse.

Yes, you arrive at some very interesting conclusions in the book about where the Occupy activists went wrong, notably in terms of the failure to develop a viable alternative to representative power structures, and more especially, the failure to develop structures that would allow them to make a claim to legitimate sovereignty and a transfer of power eventually. We’re seeing this in Spain now, with the new mayors of Barcelona and Madrid, who came out of the Indignados movement, and with Syriza in Greece as well. What lessons can we take from Europe’s movements?

If you look at what we were doing at Occupy Wall Street, we went into these squares and started to hold these consensus-based general assemblies. And it was a kind magical thinking that we could manifest sovereignty in this way. We were basically like, “If we do these behaviours, if we’re consensus-based, then the police can’t really smash us, because we’re a purer form of democracy.” And what we learned is that, actually, you can’t get sovereignty in this world by doing that. It doesn’t matter. And I think that maybe came as a little bit of a shock.

Are these the First-World myths we’ve been raised on about democracy?

Exactly, not only that our elected representatives respect mass movements, but that they would respect something that was so genuinely democratic. I mean it was a non-violent, consensus-based space. And so I think we’re faced with a question, which is: “How do you actually gain sovereignty in the world that we live in?” There are only two ways: you can win wars [or armed insurrections], or you can win elections. And war, I don’t think it’s a viable strategy. So we’re left with elections. Is that possible? Yes it is, because we’re seeing it in Europe. So the challenge is, how do you use social movements to hack elections?

The economic contexts are quite different though. In the US it’s quite a bit worse than in Canada, but if you look at the unemployment rate, it doesn’t compare to Mediterranean Europe. I wonder whether you think people’s parties can break through here?

We don’t know what the future holds. Maybe there would be some sort of massive stock market crash, or a major economic crisis around the time of an election. I mean, you really don’t know. To me, if you look at the American context, what’s really funny is that everyone says that a third party isn’t possible, but now that Trump is about to get the Republican nomination, all these establishment Republicans are saying, “Well, we need to start a third party.” It’s a joke. So, I think there is a way we close off our minds by saying that something is not possible, when instead we should try to visualize it, and figure it out. Because anything can happen.

I wanted to get to another major focus of the book, which is how commercialist culture has effectively colonized our minds, to the point of stifling our ability to imagine alternatives. You write that activists must be “mental environmentalists, as concerned by the health of our inner worlds as with the natural world,” and say that “kicking consumerism out of our heads and finding solutions to global problems are one and the same fight.” I would love if you could explain this relation in more tangible terms.

One of the things that I think is stifling activism is that our imagination of what is possible has been constrained. A lot of people have forgotten that there have been these dramatic transformations of society in the past, and I think that is [because of] this illusionary world we inhabit that is created by advertising and the media. It’s as if we have a mental environment that mirrors our physical environment, and the pollution of our mental environment by advertising and commercialism not only stunts our imagination but also impacts how we live our lives each day.

There’s one particular passage in the book that struck me, when you write, “When we cannot name the species of trees, animals and insects around us but recognize instantly the commercial logos [...] we don’t see the world that is disappearing around us.”

Yeah, there’s this spiritual writer who said something like, “When you’re hungry, all you see are restaurants. When you’re horny, all you see are attractive people. And then when you’re looking for God, you see him everywhere.” Or as I would say, when you’re seeking revolution, then you see possibilities for it everywhere. So what you look for is what you find.

One of the scenarios you paint for promising avenues towards revolution is this idea of [activists moving to rural areas to organize] a rural populist revolt. This rests in part on the fact that rural areas are less saturated by commercial culture than urban areas. I couldn’t help but think, of course, that the majority of people in the West live in cities, and that by 2050 they’re predicting 80% of humanity will. So considering that, what advice would you give for urban mental environmentalists?

There’s this nice Sufi way of looking at it, which is that what we need to do is develop our capacity to live amongst the pollutants and keep ourselves protected. So I think there are those two different approaches. I live in a rural area myself, a city of 280 people. In the rural areas it’s easier to just not be exposed because there are no billboards and no big corporations. But in the urban areas it’s beholden on activists to learn to develop those tactics of defending their inner...

Mental tactics.

Yeah, mental tactics. And it makes us stronger. So I do think there’s something to be said for not just fleeing, but also staying.

Is it fair to say you’ve sort of given up, at least in the short term, on actually reversing consumerist culture?

No. I mean, who knows what’s going to happen tomorrow. For example, in Sao Paolo, Brazil, they banned all outdoor advertising.

We [sort of] did that in a borough of Montreal too, actually.

Oh, nice. So see, it seems conceivable to me. I can imagine a social movement that arises and one of the things they achieve is banning advertising. Why not? Or taxing advertising. But I do think in the meantime, you have to first recognize the situation, basically that advertising and commercialism is a kind of weapon that’s used to diminish our spiritual capacity for revolution.

And is this where these tactics of meme warfare and the sort of culture jamming that Adbusters does come in? To try to facilitate that critical distance between people and commercial culture?

Yeah, for sure. And even the term “mental environmentalism” is from Adbusters. Adbusters’ subtitle used to be “The Journal of the Mental Environment.”

Oh, that’s right.

Yeah, so this is one of the ideas that I picked up when I worked at Adbusters and kind of developed the philosophical basis for.

Another interesting argument you made in the book is about the place of women in social movements. You mention that women were central to Occupy, in particular regarding the consensus-based assemblies. You argue that women will make the next social movement too, even predicting a “global female awakening.” I couldn’t help but remark that the new mayors of Barcelona and Madrid are both women. So I was wondering if you could maybe try to explain this connection a bit more, between a women’s awakening and these new movements for more participatory and egalitarian politics.

For me, the thing about revolution is that it always comes as a surprise, it always looks different. So what we need to do as activists is develop a revolutionary intuition that helps us get a sense of where that next surprise comes from. No one can know for sure.

When I check in with my own revolutionary intuition, I just get the sense that women are the ones who have, first of all, that inner fire. And I think also that the pollution of the mental environment affects men extremely, because of videogames and pornography, even just walking around cities and the sexualization that we see.

So on the one hand I think that we have a kind of male cultural crisis—I’m not the first person to point this out. But on the other hand I think that women have a kind of potential for global solidarity, because they’re oppressed in every country, even in Western countries, but in different ways in each. So I can imagine a kind of awakening, where one day we wake up and look outside, and there are women of all ages protesting in new and different ways, and people are rushing to join the movement.

Maybe their way of communicating is a part of the solution to the global challenges we face. There have been interesting studies about how just having one woman in a discussion makes the creativity level of the group go up. And I think that once women actually realize that they can be in power, and that maybe that would be better for all of us if most governments were run by women... [laughs].

It certainly couldn’t be worse...

Yeah, there you go.

This idea of transnational solidarity amongst different peoples, that’s also a core aspect of your vision of a postrevolutionary future. You view a world where current elite-governed nation-states have made way for people’s democracies—essentially, a horizontal confederation of free, bottom-up, autonomous cities. You’re certainly not the first person to say that this is the direction the world is going in, but I’m sure many readers would also look at the world around us now, at the resurgence of nationalism in Europe and in the US, for example, and say you’re dreaming. So I wonder where you find reasons for optimism to think that. Even if people’s movements could manage to win elections in cities, which we’ve seen can happen, would people be ready to give up on nationalism?

I think it really is the only solution. Strategically speaking, the only solution to the global challenges that we face is a global social movement that can win power in multiple countries in order to carry out a unified agenda. So it’s like this ultimate goal. [...]

What we’re dealing with here is imagining how there could be [such] a global movement that’s still able to manifest differently in each country without there being this centralized party leadership. That sounds hard to imagine, but we did kind of achieve that during Occupy Wall Street. It spread to 82 countries. The people in New York weren’t telling the people in Canada, “Do it this way.” We left it up to each city.

And if you look at the discourse of the Indignados, versus the discourse of Occupy Wall Street, versus the discourse of the carrés rouges here in Quebec, they echo each other remarkably. You do mention this in your book, how you feel the “global 99%” are more unified now than ever. What makes you feel that?

Partly, I think it really is the Internet, and our ability to tune into the struggles that are going on everywhere. During the protests of 2011 and 2012, there were these interesting sociological studies where they went into Russia and looked at who was protesting there at the time—that movement was obviously crushed—but they found out, “Oh, it’s hypereducated youth.” It was demographically the same kind of people that were inspiring Occupy Wall Street. So there is a kind of global culture that seems to be arising that underpins these movements.

And so, to get to a place where people start seeing these links of solidarity more, start really feeling solidarity with people around the world, what do you think the main blockage is right now? Because it seems the emotional attachment and allegiance is still mostly to one’s national identity, which is structured in a vertical way.

I would say it has to do with the failure of revolutionary imagination. I think people have given up on the possibility and desirability of revolution, and a lot of people don’t see [how] it would be better. But once people start to understand that only a global revolution can solve the global challenges that we face, then we’ll see more people getting into this idea. [...]

It’s the only solution. But you can’t really show people that rationally. I think it’s something that we have to experience: the feeling of being part of a global movement.

This interview has been edited.