When I was around the age of six, I couldn’t fall asleep without knowing someone else was awake. Since my parents have always been early sleepers, this resulted in a near-obsessive bedtime routine that lasted for years. If I were awake to hear the electric ping of the television turning off for the night, I’d listen to the sound of my younger brother’s breathing in the room next door. If he was sniffling, it meant his chronic allergies were keeping him up again and we were awake together. But if I outlasted both, which was often, it meant I was truly by myself, and vulnerable to hearing all sorts of horrible scratches, clicks and creaks—sounds a house only seems to make when you’re alone.

When this happened, I’d walk up to my window, look past the backyard, and into the windows of other people’s houses to watch the lit rooms for proof I wasn’t the only one awake. Curtains moving. The shadow of an adult vacuuming at 2 a.m. The harsh blue flicker of an action movie against a white wall. I needed so badly to feel company that I would create, invent, extract it from whatever seemingly innocuous details I could.

I’ve become much better at being alone in the two decades since. I’ve lived, slept and dined alone, and done all three with company. I’d mostly forgotten about this near-creepy childhood habit until a couple of years ago, while reading an essay by Ariel Levy in 2013. “Even if you are not Robinson Crusoe in a solitary fort, as a human being you walk this world by yourself,” she wrote. “But when you are pregnant you are never alone.” The essay doesn’t end happily, but even then, as someone utterly confounded by the idea of motherhood, my breath caught in recognition. “Maybe one day,” wasn’t the thought, but something closer to, “oh.” It felt selfish to admire pregnancy for this reason, but it also felt good.

In the couple of months I was recently pregnant I learned that, in the early weeks at least, this company isn’t so much a knowable presence as it is a series of questions and habits, all of which construct a new relationship with your self. Even though I’m no longer expecting a child, I’m accompanied by some of these questions and habits still. My outfits are softer and mostly waistless. I’ll moisturize twice after every shower for skin that’s no longer scheduled to stretch. Though I’ve been a stomach sleeper for years, I’ll often wake up on my side, only to remember such care is no longer necessary.

It’d be the easier conclusion to think that this continuance is a form of grieving—a way of working through the pain of what so much of medical literature tells me, for a woman of 28, is just a false start. But I refuse to believe either of these things. I refuse to believe the latter, because to use the words “false start” feels like a minimizing and betrayal to my body and this thing it has both done to itself and endured. I refuse to believe the former, because there seems to be so little inside or outside my life to help me understand what this type of grief is supposed to even look like.

Perhaps it’s most accurate to describe these habits as a form of biding time. In a lot of ways it feels as though I am just standing here blinking, my hands still in the shape of a promise they were holding that has since disappeared.

*

It’s disorienting and frightening to realize how hard you can come to love something without thinking for too long about its existence in the first place. Here is one way to fall in love with an idea.

First, feel a twinge in your abdomen and left breast while watching a terrible horror movie, and despite having never felt the need to, pull out a pregnancy test because you’re horrified by a new and distinct awareness of what’s happening in your own skin. When the test comes up positive, cry on a couch for an hour until your husband comes home, and take the four more tests that he afterwards picks up at your request just to be sure. Go to a doctor for yet another test. Start taking vitamins.

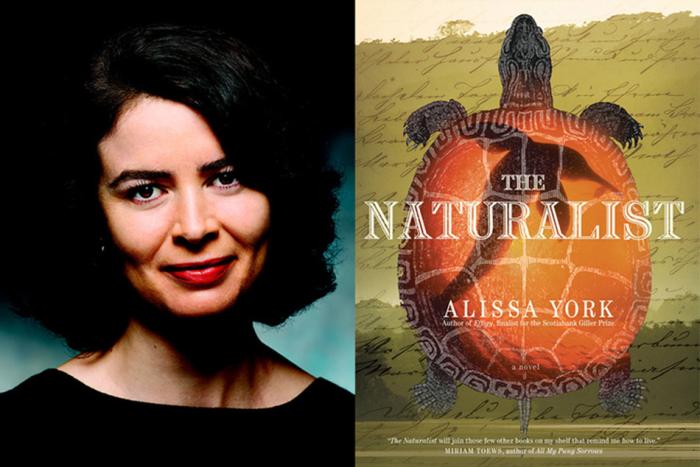

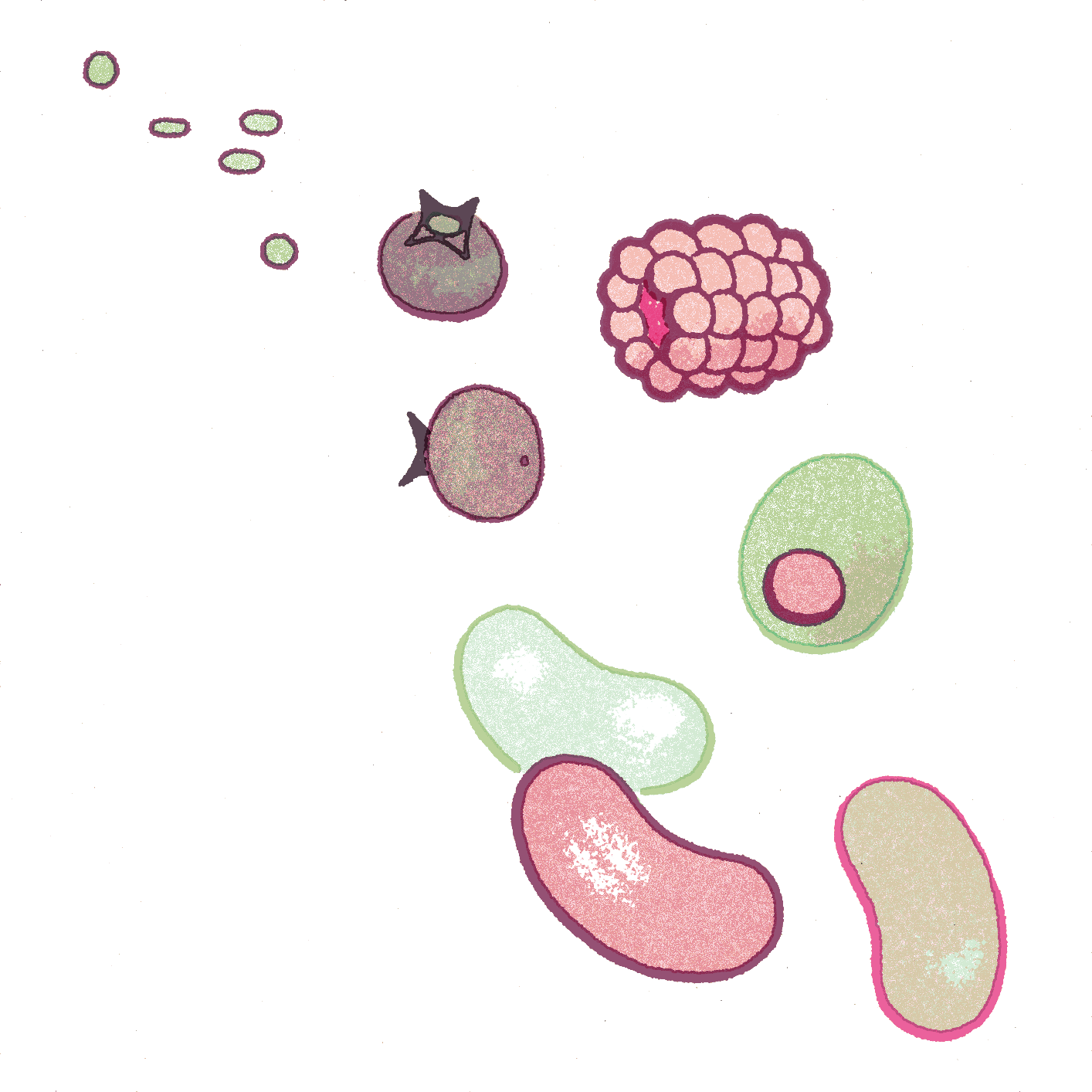

Call your mother, who immediately starts crocheting cottony, white receiving blankets and makes plans to retire early. Freak out about the interminable graduate degree you’ve been working on. Scour the city for prenatal yoga classes that don’t cost you the firstborn you’re taking the classes for in the first place. Sign up for email newsletters that mark the growth of your baby in food metaphors, despite having despised the cartoonification of prescribed women’s narratives all your life.

I worried over that last detail in my head like a little set of prayer beads in the twenty minutes before my husband arrived.

Find yourself pulling a complete 180 after getting fish-hooked on the beachy smell of vinegary ketchup and food court french fries during lunch hour, and giggle. Allow your husband talk to your stomach each night: Goodnight lentil, goodnight blueberry, goodnight jellybean. Feel ashamed of this for a minute, and then angry with yourself that you felt ashamed in the first place.

Search frantically for a midwife in a province where demand has far outstripped availability, and get placed on every wait-list in the city while hoping an obstetrician can see you in at least the first eight weeks. Spend New Year’s passing off glasses of club soda as gin and tonics. Open up a savings account to squirrel away dollars for an education fund. You’re just barely two months pregnant. You’ve told no one beyond your parents, and one or two friends who are now parents themselves.

One of these friends gifts you the loveliest hand-me-down: a pale yellow onesie with the words “Fuck The Patriarchy” silkscreened in faded purple cursive across the chest. On rare nights, you allow yourself to unfold that little piece of clothing, and imagine a tiny, wiggling body filling it out. Now, even afterwards, you sometimes still do.

*

There is a very convincing feeling of control that the secrecy of early-pregnancy affords you. At a time when you’re still trying to plan for parental leave or whether or not that extra cup of coffee is going to brain-damage your would-be child, you have a say over who knows, and when—and therefore whose advice you care to solicit before the relentless fire hose stream of instructions from extended family, co-workers and random people off the street begins later on.

But to be newly pregnant is also to feel uniquely unsafe. If not from crushing uncertainty over timing, childcare, ideas about parenthood, then about the pregnancy itself. Commonly cited numbers suggest 10 to 20 per cent of all pregnancies end in miscarriage, about 80 per cent of which happen in the first 12 weeks. What we unquestioningly call common sense suggests this is precisely the reason for the three-month rule of telling. As Alexandra Kimball wrote in the Globe and Mail last December, “A woman who doesn’t announce her early pregnancy will not have to announce its loss. She can move on as if it never happened.”

The very real danger beyond pregnancy loss itself, she writes, is in the statistical likelihood of having to do precisely this.

It was the first time I tried to justify pain, as if pain ever needed such a thing, and is one of a collection of new habits I’ve picked up in the weeks since miscarrying that may or may not stick around. Tension seems to like to rest in my right jaw, so I crack it the way some crack their knuckles. I shave my legs more often in preparation for emergencies that may or may not materialize. I have become a far more indecisive person, and will agonize over the most seemingly insignificant choice. Shortly after I bought that bra, I stuffed it into a drawer to wait and see if my discomfort would eventually become as evident to others as it felt to me at the time.

Only in the weeks since I stopped preparing for a different outcome have I allowed myself to take it out, still wrapped in its flaxen tissue, and think about the future. Choosing whether or not to return that bra somehow evolved from a simple transaction into a definitive statement about what place I believed parenting had in my life. To keep it, unworn, felt like something firmer than hope: a resignation to somehow make this balloonish black-and-pink polka dot thing of use, even if it meant opening my husband and I up to the recurrence of a type of loss I now knew was possible. To bring it back to the store would have meant a rejection of all that, and might also have made the project of moving on a bit easier.

If talking about a grief like this is ever going to become an easier story to tell, this type of ending has to be OK. There’s a comfort in saying this without having waited for a neatly wrapped ending-of-a-baby announcement or a newfound resolve to live a life without parenthood, but: I haven’t decided, and I have it still.