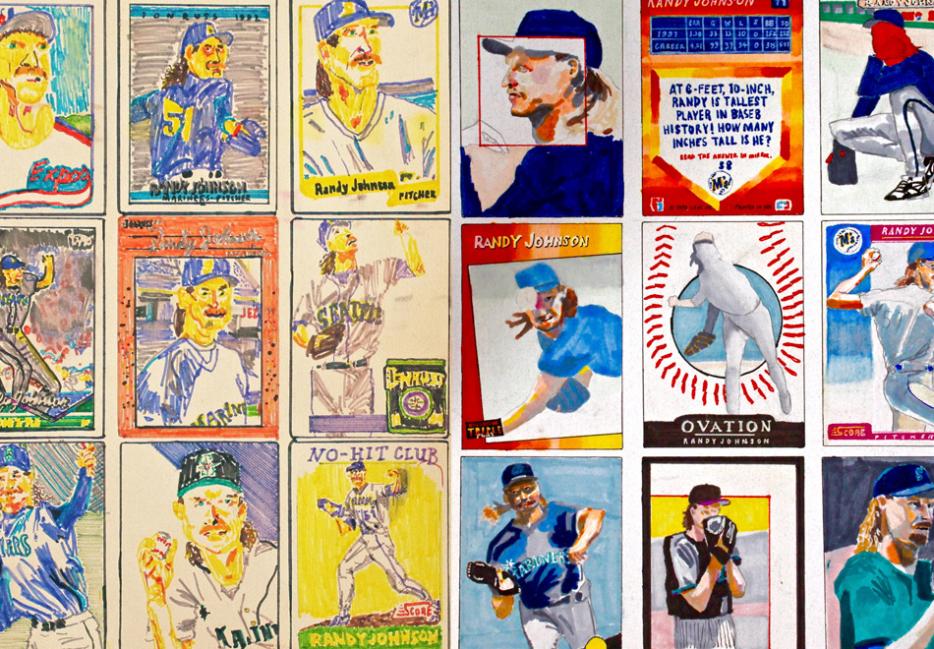

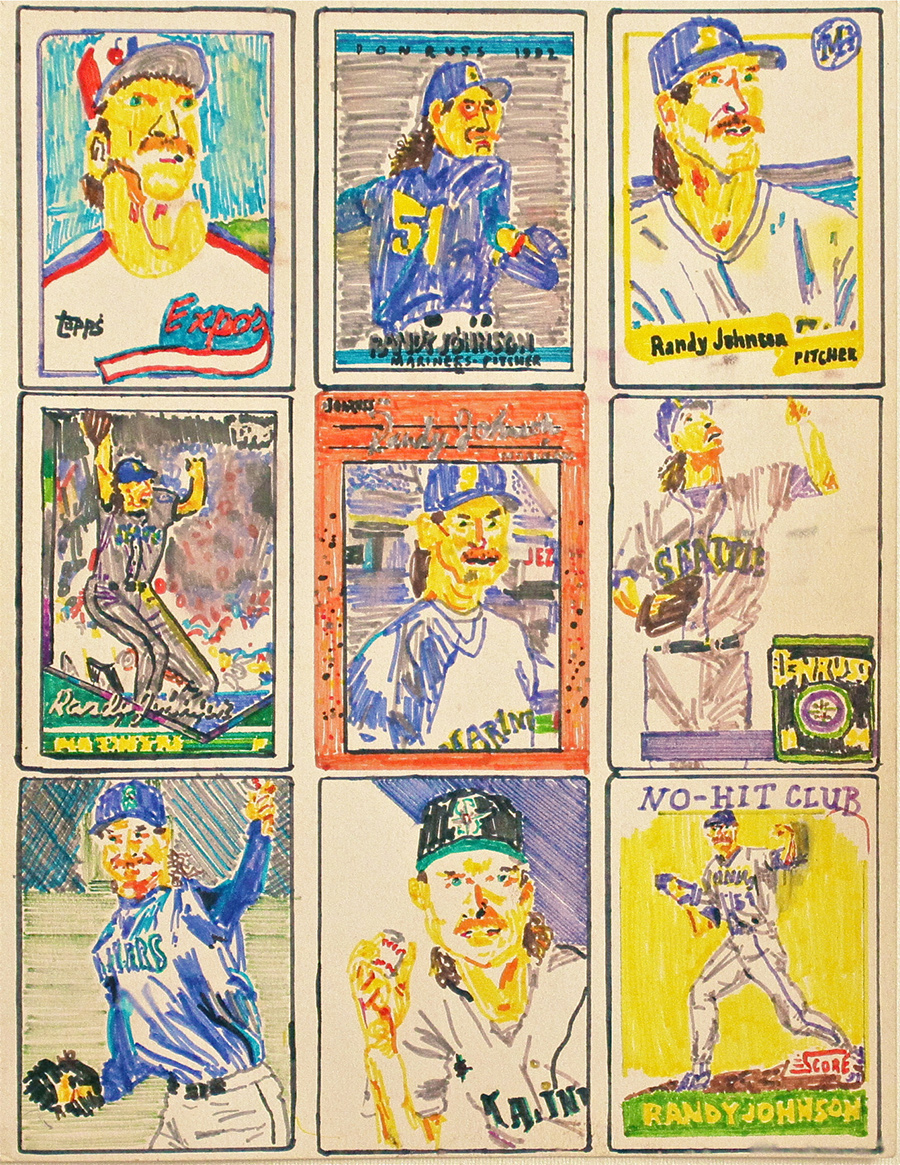

Hunter Jack was in Cooperstown, New York, trying to make baseball fans understand something they couldn’t collect. He’d driven from Queens and rented a table in the Doubleday Field parking lot, near the commemorative Sandlot Kid sculpture, to display his 185 hand-drawn baseball-card-sized portraits of Randy “The Big Unit” Johnson. Over the past twenty-four months, he’d obsessed over Johnson’s hawk-like face, his body like a windmill knocked off kilter, and rendered the pitcher in everything from pen and ink to collage.

It was Hall of Fame weekend, and Randy, along with Craig Biggio, Pedro Martinez and John Smoltz, would be immortalized as a baseball legend in the coming days as a 2015 inductee. Fans of the game stopped by the booth where Hunter sat with his girlfriend Caroline, his mom Laura, and a few Canadian friends, to look at the three-by-three portrait grids encased in plastic. Someone inquired if Jack and Johnson were related. Another wanted to know if he could buy a portrait. Jack’s friend Ryan McColeman had to tell the guy they weren’t for sale.

“Why would you make art and not have it for sale?” the fan asked. “That doesn’t make any sense.”

It seemed as though everyone except Jack was selling something at Hall of Fame weekend. Autographs from retired players who, unlike Randy, will never make it into the Hall of Fame, went for five dollars apiece. A signature from a more storied player cost $100. You could buy game-worn hats, and game-used bats, and bags of dirt from old stadiums. Johnson himself wandered into town on Thursday with four security guards to pick up some vintage baseball shirts from Mickey’s Place on Main Street. (Unfortunately, not everything in the store fit his 6’10” frame.) While there is no right way to be a fan, enthusiasm is often expressed commercially (baseball revenues exceeded $8 billion in 2013), and Hall of Fame weekend is expressive. What Cooperstown really trades in is Americana: Jack’s friends from Canada were counting American flags when they first arrived, but stopped when they saw one made entirely of baseball bats. Hall of Fame weekend is the standout event in a town that trades on baseball, the myth therein, and the money to be made from it.

But Johnson never quite seemed to buy into the myth. A five-time Cy Young winner, ten-time MLB All-Star, and holder of the record for the second-most strikeouts of all time (4,875), he loved playing baseball, but had little time for the spectacle surrounding it. He makes his success sound like a random accident of fate and genetics augmented by a lot of hard work. With his flinty eyes, peaked nose, and legendary height, Johnson’s impossible to miss. “He’s a one of a kind body, like a natural freak occurrence,” Jack said. The popularity that accompanied his success fit him about as well as an off-the-rack suit would a man of his size. His reaction to media and fans sometimes engendered ill will, but Johnson insisted it was a reticence bred of humility, inspired by lessons passed down from his dad. Since retiring, he’s spent his time pursuing professional photography. He talks about being one of the best players in the history of baseball the way most of us talk about the weather. Not to say he takes it for granted. In his Hall of Fame acceptance speech, he spoke more about others than he did himself, thanking all of them for being there on “his special day.”

But it’s not Johnson’s outsider status, or his artistic pursuits, which led to Jack producing his collection of portraits. When I asked him why he decided to start drawing Johnson one day and then not stop drawing him for two years, his answer was simple: “Because he’s the tallest.”

*

There was no baseball game the day I first met Hunter Jack, so instead of heading to a stadium, we went to Wayne Gretzky’s, a hockey-themed bar in downtown Toronto, just down the street from the Rogers Centre. It seemed like a good place to talk about how to be a fan. As soon as we sat down, Jack complimented an Eighties-style portrait of Wayne above a banquette that looked like the debut album cover of a mall-tour heartthrob, or a Tiger Beat pin-up done in pastel. While Jack hasn’t done any Randy portraits in this specific style, he’s rendered the player pretty much every-way-else. He pulled the plastic sleeves from his bag, and though I’d looked through the drawings on his Tumblr page before, I was struck by the tactile experience of holding them. There was something about the scale, stacked up in the sleeves, the repeated imagery cast over and over in different ways, which felt meditative. It was the feeling of a long run, the feeling of conditioning training. Repetition with purpose that allows you to notice different muscles every time.

But there was also a narrative: Randy with his head in his hands, sitting on the bench. Randy with his leg in the air, impossibly long arm rocketing a baseball in front of him. Randy wound up, ready to explode. Randy as force. Randy as ferocity. Randy as someone staring down the concept of failure and baring his teeth.

There was a baseball game the night before I interviewed Jack in Toronto. He and his friends thought about buying tickets. It was already the third inning and could have gone either way, so they flipped a coin. They didn’t go. “That’s where I’m at right now.” But a few weeks after Hall of Fame weekend, Jack attended a minor-league game, between the Staten Island Yankees and the Aberdeen Ironbirds, with about 100 other fans. From the stadium, he could see the harbour and the Manhattan skyline. There were family-style competitions between innings. “The saltine challenge! Egg tossing! Baserunning races in sumo suits!” he said. “The Ironbirds won, but it was close! The tying run got thrown out at home plate in the bottom half of the last inning.” It felt good, he said.

On the day it was announced that he would be inducted into the Hall of Fame, Randy Johnson did a press conference in Arizona. He said the experience he was most grateful for, and the experience that perhaps explains why he chose to represent Arizona in the Hall of Fame, was winning a world series. When fans come up to him at Starbucks, that’s what they talk about. That’s where the players and the fans intersect in experiencing, together, what Johnson might call “a special day.”

“They don’t talk about the Cy Youngs. They talk about the World Series,” he said. “Well, they also talk about the dead pigeon, too.”