Being lonely can be painful. As a species, we’re born with an innate need to be with others, and the physical and mental distress caused by too much isolation is proof of this fact.

To frame this another way, for nearly all of our time on Earth, to be alone was to be in danger. Thus, the feeling of safety and well-being derived from human connection is both an evolutionary quirk and one of the more meaningful experiences we can have.

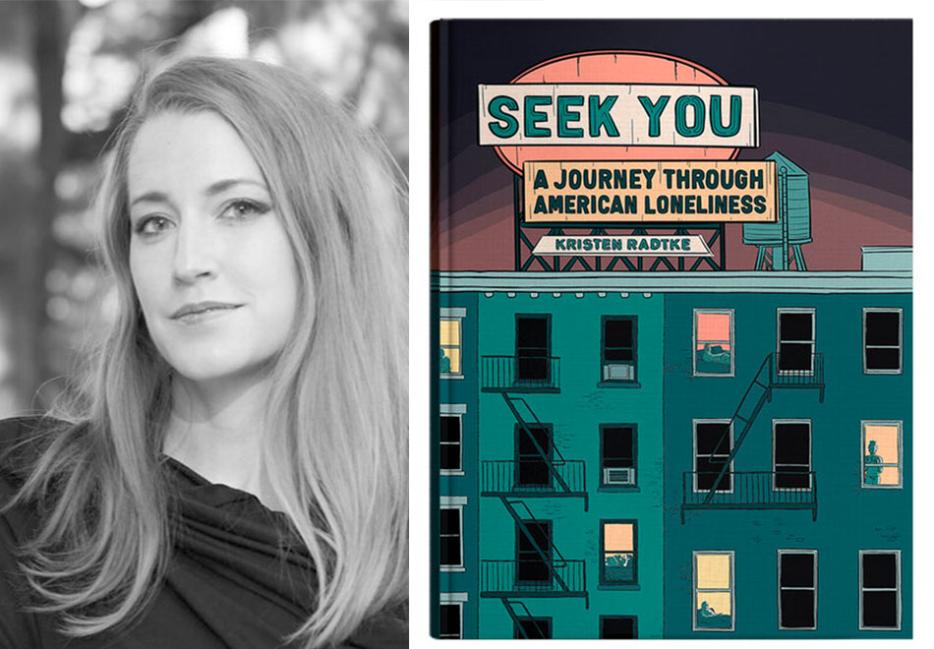

With incisive prose and distinctive photo-based illustrations, Kristen Radtke hones in on this complex subject in her book, Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness (Pantheon). A sweeping essay in graphic form, Radtke’s sophomore release reflects on laugh tracks, cowboy archetypes, Princess Diana, romantic comedies, mass shooters, and the early days of the internet. She describes a call service for solitary senior citizens, the infamous isolation studies of an anguished psychologist, and the industry of professional cuddling geared toward people starved for touch. She also discloses her own loneliness and conveys how fear and vulnerability are widely shared, writing, “I want us to use loneliness—yours, and mine—to find our way to one another.”

Whether felt in our brains or our bodies, Radtke tells us, the ache of solitude is our signal to seek company. While tinged with melancholy, her book provides a compassionate perspective on the meaning of loneliness and the importance of human connection. The Brooklyn-based author and I recently talked about her latest book and how better understanding loneliness helped her to feel less alone.

Andru Okun: Seek You is your second book. What themes or motifs do you think you’ve carried over from your first, Imagine Wanting Only This?

Kristen Radtke: When my first book came out, I remember there was a review that said something about how I was grappling with isolation and loneliness, and I was like What do you mean? I’m not doing that. I didn’t recognize that was a theme I was working with, and I think sometimes it takes me a really long time to recognize an obsession I have in my work, or the fact that I may be working through something in my writing before I’m conscious of it. First books are complicated, difficult things, and I didn’t know when I started writing that I was writing a book. I just thought I was writing essays, so it came together in a very different way than this book, which felt like I had an intentional purpose when I began.

There’s less memoir in this book and more reportage and research. Was that intentional?

I never wanted to write a memoir. My first book sort of became one over time; I thought it’d be much more like Seek You in that it’d be more outward-facing, but early readers were asking for more personal information, like a personal guide to help them through the research. I think that’s the case for this book too—an early draft didn’t have any memoir or personal elements in it. I had a friend who pointed out that I’d done all this research, but they didn’t understand why I’d assigned myself this work. They wanted to see my personal stake in it.

There’s also a discernible difference in your drawings between your first and second book. You’re now using colour, and the visual storytelling is more complex. As an author of graphic non-fiction, do you feel like the drawn components of your work grow in tandem with your writing?

When I draw, it changes what I need to say and how I say it. I’m also communicating by using language in the images, and, of course, images are a kind of language in themselves. I can’t quite remember how the form started for this book—it isn’t sequential or in panels; it’s not a comic in the same way. I tried to remember how I came to that, and I really can’t. It just became the form that made sense to me as I was working.

You note that you started this book in 2016. This was also the year scientists first identified the part of the brain that responds to isolation. Was this discovery part of what prompted you to pursue this project or was this coincidental?

It was coincidental. I didn’t know anything about the science of loneliness before I began writing about loneliness. All of my research was done in service of this particular interest.

So, what exactly was the catalyst?

I think 2016 was a lonely time for a lot of people. It was a challenging year. I’ve looked for research on whether loneliness spikes during election years in America. That research has not been done, or at least it has not been published publicly. But it seems likely to me that that would be correct because it does isolate us from each other in a pretty stark way.

Loneliness traditionally spikes at three ages—your late twenties, your mid-fifties, and your eighties. This makes sense because it’s when a lot of people go through a lot of life changes. I was in my late twenties, and I was just trying to figure out this transition into proper adulthood and what my life would look like, which can be a kind of isolating experience.

I recently read Elisa Gabbert’s essay on loneliness that references some of the graphic essays you published before the release of Seek You. She makes what I think is an excellent point regarding writers: while we’ve come to think of solitude as a necessity, we really thrive off of interactions with strangers and crowds, that being around others engenders “a complicating energy that produces ideas.” I was wondering how you felt about this concept.

It’s hard for me to say if that’s unequivocally true for everyone, but for me that’s definitely true. I find myself surprised where ideas come from, because I can never track what’s going to trigger something for me. It might be a conversation with a friend, a ride in the subway, or a thought I have as I’m falling asleep that I have to write down or it will be completely gone the next day. I think that we do like solitude, but I think it is really important that we separate solitude and loneliness because they sometimes overlap but they’re not the same. Someone can be very solitary and not be lonely, and another person can be extremely socially active and be cripplingly lonely.

What does it mean for loneliness to rest, as you write, “in the space between the relationships you have and the relationships you want?”

So, there’s no formula to fix loneliness, no way to easily determine how much social interaction one person needs. You can have a very outwardly fulfilling personal life and still feel unfulfilled if your relationships are not providing you with the meaningful stimulation that you need. That’s one of the reasons I think that political divides make us more lonely. I hear a lot of people say that when Trump emerged, they just stopped talking to their uncle or their dad about politics. But as we know, the personal is political, and to not talk about politics means resisting talking about a big part of who we are, our belief system. And if we can’t talk about our belief system, it’s difficult to have deeply meaningful, authentic interactions. Even with a really active social life, someone can feel a kind of longing for connection or for a witness so they feel seen, and that can lead to a sense of loneliness.

Did you personally have these types of experiences where you stopped talking to a family member or a friend over political disagreements?

Yeah, I come from a very conservative place. I think that it’s very painful for people who have different political ideologies from their family, for sure.

Why do you think separation is such a large part of American culture?

I wrote about loneliness in America specifically because I’m American and American culture is what I understand best; but I’m also very interested in how loneliness is kind of coded into our ideology and our value system and how that’s a by-product of our insistence on individualism. If we look at the American dream, it’s this idea of the white picket fence, a big yard, and the ability to literally block yourself off from other people. You can define your space and claim it. Where I come from, your measure of success is how much land you can afford to have—how many acres—and there’s this pride in not being able to see your neighbours. You’ve made it if you can be isolated in that way. And I’m not saying there’s something wrong with wanting to live in the woods (there’s not), but I think that when we start to prioritize the self over the community—which I think we consistently do in America, and I think we saw this in the divides that arose during COVID—it starts to get very dangerous. That prioritization of the self has been a big part of our thinking probably since America’s conception.

It’s as if loneliness and separation are built into the architecture and the layout of our communities.

Absolutely. There are not that many community gathering spaces that aren’t based around commerce. When I was in high school, we would go to the mall. It was of course a place centred around consumerism and capitalism, but now what are the gathering places that people have? Some cities are better about green spaces and public parks, but we don’t have town squares or places where we can get a town-square feeling in a way that is quite common in other cities across the world.

Wealth is a factor of loneliness as well, right?

Generally, the more chronically lonely countries are wealthier. This is clear for a lot of reasons: wealthier countries have a skewed relationship towards work and a lot of the work is more isolating than it is in less wealthy countries. Office jobs, for example, can be quite isolating. People in wealthier countries are more likely to be able to afford to live alone or to delay marriage; also, wealthier countries have longer life expectancies, so you’re more likely to see people that you love die and you’re less likely to live with your family during that time.

There’s a lot of caveats to this, though. A country that is at war is generally an extremely lonely place. Hannah Arendt writes about this in her book, The Origins of Totalitarianism; she consistently found that loneliness was out of control in countries where people lived under dictators and couldn’t trust their neighbours.

Your book suggests that our perceptions of loneliness differ depending on our personal experiences of gender socialization. What drew you to examine this construct?

Honestly, I think it was Sandra Bullock. In the before-times, I used to fly a lot for work and it was sort of my favourite moment to watch terrible movies. It’s just one of the greatest pleasures in the world, to detach from any responsibility and just watch a stupid rom-com from the ’90s. And so, I’d watch a ton of Sandra Bullock movies, and I started to notice she was lonely in every single one, sometimes in the same tropey way and sometimes in very different ways. In Gravity she’s literally shot into space, and in other movies she’s a sort of hapless twenty-something in her tiny studio apartment trying to make it as an assistant in a cutthroat industry. But she’s always on the outside, and I was interested in that because the formula for how they solve that is relatively consistent, and it often involves making a romantic connection or occasionally a friendship. It’s very different from how men are portrayed. The rise of the anti-hero reinvigorated the cowboy trope. If you look at someone like Don Draper, Tony Soprano, or Walter White, they’re all cowboys and basically renditions of the same characters. This isn’t to say that it’s not entertaining, but they get to be sexy and coveted and alluring in a way that a rom-com heroine doesn’t get to be.

Can you explain the idea of contagious loneliness?

That was one of the most shocking things I researched, although once I understood it the concept made complete sense to me. I think it was something I was already recognizing in my personal life and my relationships with my friends. The scientist Dr. John Cacioppo discovered through his research that loneliness can become contagious and be transmitted to up to three people removed from one lonely person. Basically, once we enter a state of loneliness, we’re likely to start self-isolating. It’s kind of like depression or any kind of insecurity or self-consciousness—we start to assume other people don’t like us and that they don’t want to hear from us. We imagine that rejection will happen before that rejection takes place, so it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Once someone is lonely—particularly when someone is chronically lonely—they kind of cocoon into themselves. So, if I’m isolating, and I have a best friend, she may feel rejected by me and stop reaching out, so then that relationship will become strained and severed and she could feel wounded, which creates a type of loneliness in her that she could then pass along to another person.

How do you think our culture’s idealization of the past ties into present-day experiences of loneliness?

I think it’s very easy to say that everything has gone to hell and things used to be so much better. Every generation has felt like This is the end. If you go back to ancient cultures, there was a sense that the apocalypse was coming. We often prescribe that to technological advances—as we make progress, we’re lamenting the things that we lost. And I think that’s really natural, but it’s also slightly misguided because things get sepia-toned and hazy, and we forget the difficulties and complications of the past. I think about this a lot when I hear complaints about social media, and I’m not saying social media isn’t a huge problem that has done enormous damage to our understanding of truth, news, our electoral system, and our relationships to each other. All of those things have been very damaging and, in a lot of ways, catastrophic. But I think that we assign a little too much blame to new technological advances like social media. I read that the New York Times wrote this scathing editorial about the invention of the telephone and how we would soon become nothing more than transparent bits of goop, or something like that. Every technological advance is assigned as the end of everything.

You write about Yayoi Kusama, a fascinating and idiosyncratic Japanese artist best known for her room-sized installations lined with mirrored glass. Why did you want to include her in this book?

When I went and saw her show, Infinity Mirrors, I didn’t know she would end up in the book, which is one of the great pleasures to me of non-fiction, that research can meld with personal experience, and you start to recognize connections. This maybe goes back to what we were talking about earlier about how it can be energizing to be around strangers, because you come across things you wouldn’t in your own apartment. I think Yayoi Kusama is a very lonely figure who has lived quite an isolated life, but her work, especially at the beginning of her career, was about narcissism. One of her first pieces was these mirrored balls that people could purchase and look at themselves. Now her artwork is some of the most photographed artwork in the world, and people will wait in line for hours to go and take a selfie. They’ll get dressed up in coordinated outfits that match her show and take photos to post on Instagram. I think it’s funny that so many years before social media was invented, she predicted this phenomenon. But there’s something compelling about her work and it’s so beautiful, so it’s like Yeah, I want a picture of myself in this. At the same time, it’s easy to critique or make fun of, that people are coming to see a show about narcissism and going exclusively to take a photo of themselves.

I’ve read Seek You twice now, and both times I found the chapter on Harry Harlow and his experiments on infant monkeys just so, so sad and upsetting. It’s actually a bit difficult to get through. Tell me about Harlow’s work and your interest in it.

I became completely obsessed with Harlow. I had known about his famous surrogate mother studies, where he separated baby monkeys at birth and put them in a cage with a fake wire mother and a fake cloth mother. The wire mother dispensed milk; it was meant to either prove or dispel the idea that babies only loved their mothers if they fed them. I kept reading about him and came to know more about the studies he carried out after, which literally just became darker and darker. He started isolating monkeys in dark places without any visual stimuli for really long periods of time. He struggled a lot with his own mental health and he was hospitalized a few times and had electroshock therapy. He also had a really difficult personal life, including estranged marriages and distant relationships with his children. I just became very interested in how he came down this path of inducing isolation in animals as he was experiencing isolation himself. I tried to write about him with empathy and compassion, because I think that on the surface, it’s easy to say that he was doing these horrific things—which he was; there’s no way to deny that he was abusing those animals and that he was a sexist person and seemingly not a great, supportive partner—but I’m also interested in how we remember complicated figures in history. He really did change the way in which children were cared for, because prior to his study people thought you shouldn’t cuddle or coddle your children, and we now know that children need a lot of emotional support at a young age.

How did writing this book change how you interacted with people out in the world?

It’s hard for me to say, because just as I was finishing, the pandemic started. I think that making this book did make me feel less lonely because I understand loneliness more and I think I make more of a conscious effort to connect with other people than I used to, but I also think the pandemic has changed the way I interact with people in a similar way. It’s shown us that we actually do all owe each other a great deal, that it’s all of our collective responsibility to care for our neighbours and each other. That was the same conclusion I made in writing this book.