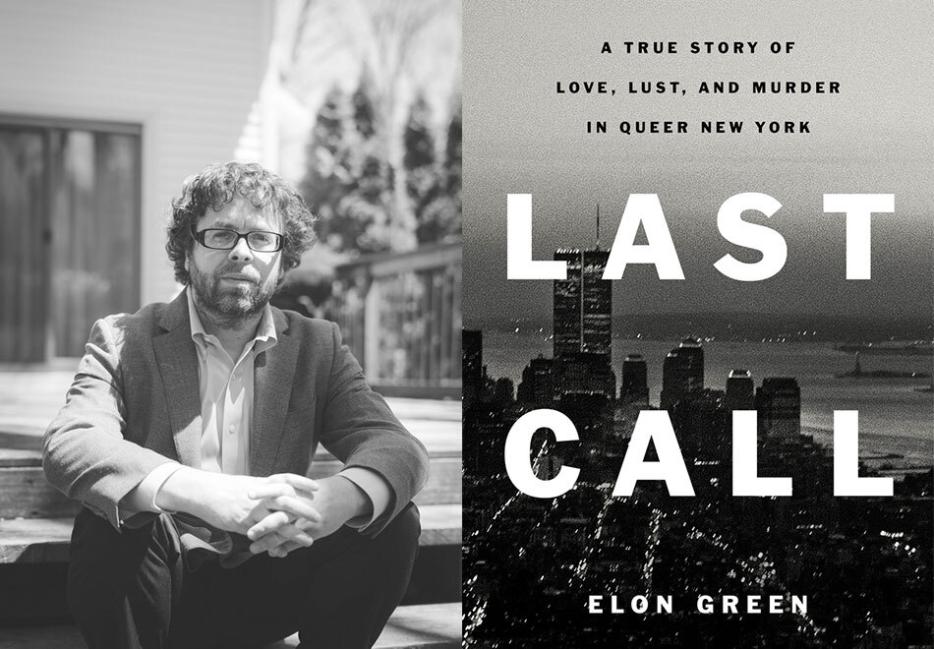

During the 1990s, the AIDS epidemic inflicted a harsh toll on New York. By ’97, more than 60,000 people in the city died of AIDS. As Elon Green writes in Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York (Celadon Books), “Death was a constant hum.”

Green’s debut recounts the lives of four men who were part of the queer community during this time. They were also uniquely connected by a different tragedy, each murdered by the same serial killer. “The Last Call Killer” was known for targeting queer men in some of the places where they felt most safe: the gay piano bars of Manhattan.

Last Call chronicles these bars, which were essential to the formation of the gay community during a time of rampant anti-queer violence. Police were of no use in responding to these assaults, and the AIDS crisis was still largely misunderstood. When the bodies of gay men started showing up in trash cans, yet another fear was introduced into the everyday lives of gay people.

“From the beginning, I viewed Last Call as a work of history with crimes and investigations holding it together,” Green tells me over a recent phone call. While his book is difficult, it provides a careful record of an era that deserves to be documented. I spoke with the author at length about how he pieced this story together and why he felt it was so necessary to tell.

Andru Okun: Last Call examines a string of murders of queer men in New York City during the 1990s. You write that these killings were largely forgotten and that you became “obsessed with the lives of the victims.” What are some of the factors that contributed to this obsession?

Elon Green: When you write about someone famous, it’s very easy. There’s a lot of existing material. I’ve interviewed Mavis Staples four or five times, and if I ever want to find out what she was doing in June of 1962, I can figure it out. Part of what was so exciting to me was that these guys were basically a blank slate and it would take a tremendous amount of work to reconstruct their lives, and doing so would be incredibly satisfying. Also, I think if you look at anyone’s life closely enough you can see something interesting. With these men in particular—one man was in finance, another was selling computers, another was a sex worker, another was a typesetter; you had men who were closeted, men who were out; one who was in the military, one who had AIDs—there was just this astonishing panorama of gay life in these four guys. That seemed like a real gift because that meant I had a lot to write about.

The murders you cover stretch back nearly thirty years. I’d like to hear about the process of researching this book and tracking down sources.

What I started with were chunks of the trial transcripts. At the beginning, I had to buy it piecemeal from the retired court stenographer. She charged me thousands of dollars for some of the transcript, and she remembered the case very well. Eventually, I became acquainted with the prosecutor in the case and he sent me everything. That transcript provided the bones for the narrative and I was able to put together an outline of events. As I was going along, I interviewed people that I found in the transcripts, whether they be family members, detectives, co-workers, people that found bodies—if they were involved in any kind of way, I wanted to talk to them. Then, of course, there was some newspaper coverage. I was just piecing the story together from whatever I could find. Once the book proposal sold, then I went everywhere. I was getting handwritten notes from detectives. I was trawling the LGBT Center archives. I had acquaintances of the murderer send me letters he had written from prison.

As far as the sources directly impacted by these murders, how have they responded to you writing this book?

So far, very positively. As far as I can tell, none of them are being blindsided. I was very upfront with what I was writing; I’d sometimes send them chunks of the book and read it to them. I didn’t want them to be surprised by anything, and if an issue was going to be raised I wanted that to happen before publication. A couple of [the victim’s] family members have read it, and it wasn’t an easy thing to do but they got through it. The fact that they finished this book seems to me a pretty extraordinary thing, because I can’t imagine doing it myself. The book is probably hard enough to read if you don’t have a personal stake in the story.

I do think some parts of this book are difficult to read, but not because of the way it’s written.

If I did it right, the whole book should be difficult to read.

You detail a lot of painful history. Did you feel at all apprehensive about telling this story?

No, it felt so necessary to do it. To strip a story like this of its historical and political context would be malpractice. In answering the question, “Why doesn’t anybody know about this case?” you have to talk about what was going on in the city and the country at that time. It was the height of the AIDS epidemic; queer New Yorkers were being assaulted to such a degree that it was basically legal to do it—there were basically no legal repercussions—and there was an indifference to their lives. Writing about this felt like not only something I wanted to do but something I had to do. One of the reasons I spent so much time on the nightlife is because it had never been written about in any real kind of way. The bars and clubs of that era, if they were written about at all, it was only through the prism of AIDS. Because, to some degree, the events in this book center around the piano bars, I wanted to make it clear to the readers (and to myself) why people enjoyed going there and what their role was in the life of the city. I wanted people to be able to see these men having a good time.

The story of Michael Sakara, a beloved regular of one of New York’s piano bars, was particularly heartbreaking. You put a lot of time into understanding the lives of these murdered men. Can you talk about how you approached writing about them?

They were already victims; that was their role in the coverage. They had been reduced to that victim status. To me, there is no point in writing something (especially a book) if you’re just going to regurgitate what’s already been done. The work that hadn’t been done was bringing these men to life on the page. The larger, loftier thing I had envisioned doing was to figure out why they ended up where they did, to understand what brought them to New York at that time.

So true crime is not a genre I’m necessarily drawn to, I don’t exactly feed off of it…

I don’t like it, either. To some degree, this book is a reaction to how I feel about the genre.

Right. So as a journalist writing the story of these men’s lives, which tragically include these extremely violent crimes, how do you decide which details are necessary to tell your story?

Yeah, that’s a good question. Very early on in the writing, I was erring on the side of putting in everything I could about the crimes and their aftermath. I just wanted to be thorough. I sent the first chapter to my friend [the writer] David Grann and he said to me, look, this is not a CSI episode. You don’t have to give the reader so much blood and guts.

Along with that, I increasingly thought of the family members and friends of the victims. Whenever I was writing something, I’d ask myself if it needed to be in the book and how would they react when and if they read it. When it came to describing the conditions of the victim’s bodies, I decided I was only going to give the reader enough information so that they understand the damage that was done. I’m not going to elide any information that meaningfully changes the situation, but I’m not going to overdo it. I tried to be as minimalist as I could, and my understanding from the reaction to the book so far is that it’s still extremely gory.

Yes. It is gory, but it seems like you were intentional about what to include, which seems like a difficult process.

Very much so. I showed chapters to a pathologist to make sure every little description was accurate. I did not want anything gratuitous.

The era you’re primarily focused on was a difficult one for gay men. You mention that The New York Times avoided writing about gay life and AIDS for years. How do you think mainstream media’s treatment of queer communities impacted prevailing attitudes toward queer people during that time?

Oh my god, it’s incalculable. There’s a reason nobody gave a shit about AIDS. Of course, the Times wasn’t the only paper that didn’t give a shit, but they were certainly the most high profile. People care about what they’re told to care about, and if The New York Times and 60 Minutes weren’t covering AIDS, that just wasn’t getting on people’s radar. And if people didn’t care about AIDS, they also didn’t care about all the things that rippled out from it, like the assaults and murders of queer people.

I was fascinated by your writing on the Anti-Violence Project. Would you talk about this group and the circumstances that lead to their formation?

AVP kept coming up in the coverage. Their role was basically to prod the police and the media into taking these murders seriously. They were keeping their own sort of dossiers on each of the victims. The more I learned about them, the more I felt that they had to have their own chapter. They’ve been this miraculous organization for forty years, and they were on the front lines of keeping the city bureaucracy honest. The reason I wrote about AVP and the conditions that produced them is because, if I didn’t do that, then the reader would not know what the stakes were, what the conditions were for queer life in the city. The reader wouldn’t understand these murders didn’t get attention—even within the gay community—because they were not unusual. There were so many deaths and assaults that four over a span of three years is basically nothing. To be able to convey that, I had to tell the story of AVP and the story of what they were fighting against.

What you’re saying reminds me of your piece last year for The Appeal on the pernicious whiteness of true crime. There’s a line where you write, “True depravity is deadly repetition.”

People have asked me why these murders didn’t get more coverage. Increasingly, I think part of it is that there are tons of murders in any given year. In New York, the numbers have been drastically diminished since the ’90s, but you’re still not hearing about all of them or even most of them. I’m willing to bet most murders aren’t covered in the newspaper. So it shouldn’t be a surprise to anybody if murders are not covered. Quite frankly, I’m grateful for the coverage that was there. Certainly, that these victims were perceived as gay was a large driver of the lack of coverage and the lack of interest in these cases, but it’s not entirely the problem.

Tell me about the “gay panic” defense and what you think this legal tactic tells us about the criminal justice system.

The “gay panic” defense basically meant that you could claim that someone of the same gender had come on to you and that you got spooked, so you assaulted or killed them. It was a legal rationalization and it was extremely common, going back to at least the ’50s. To me, it just said that the legal system was looking for a way to not care about anti-queer crime. Part of the evidence for that is that they were for so long ill-equipped to handle these cases. The Manhattan DA’s office under Robert Morgenthau had to bring people in from the outside, including the Anti-Violence Project, to teach them how to prosecute these cases.

Right. At one point you write about it as “a new kind of crime.”

I would argue that it essentially was, because even if something is technically on the books, if it’s not being treated as a crime then it’s not a crime, at least to the people who are being assaulted. If it’s not being treated as a crime, it may as well not be.

I appreciated that this book didn’t center the murderer, Richard Rogers. But when you learned about him, did you get any sense of why he may have committed these murders?

I talked to a behavioral profiler; he basically said that motive only means something in the case of a single murder. Once you’re a serial killer, you’re just doing it because you like it. People keep asking me, “Why did Richard Rogers do it?” but there doesn’t have to be some grand explanation other than that he wanted to. I’d be surprised if it was more complicated than that. Between that probability and the fact that he never took responsibility for these murders, I just didn’t give a shit about Richard Rogers.

But you did want to interview him, right?

I did, but it was mostly due diligence. I mostly wanted to talk to him to check some biographical details. The extent to my indifference to him was that in the original proposal in the book there wasn’t even a chapter about him, and I only wrote about him to fill in a narrative gap. On an emotional level, I cared about the victims, and I didn't care about him. I have tried to treat him with as much humanity as I’ve treated everybody else but, if I’m being honest, he doesn’t matter to me.