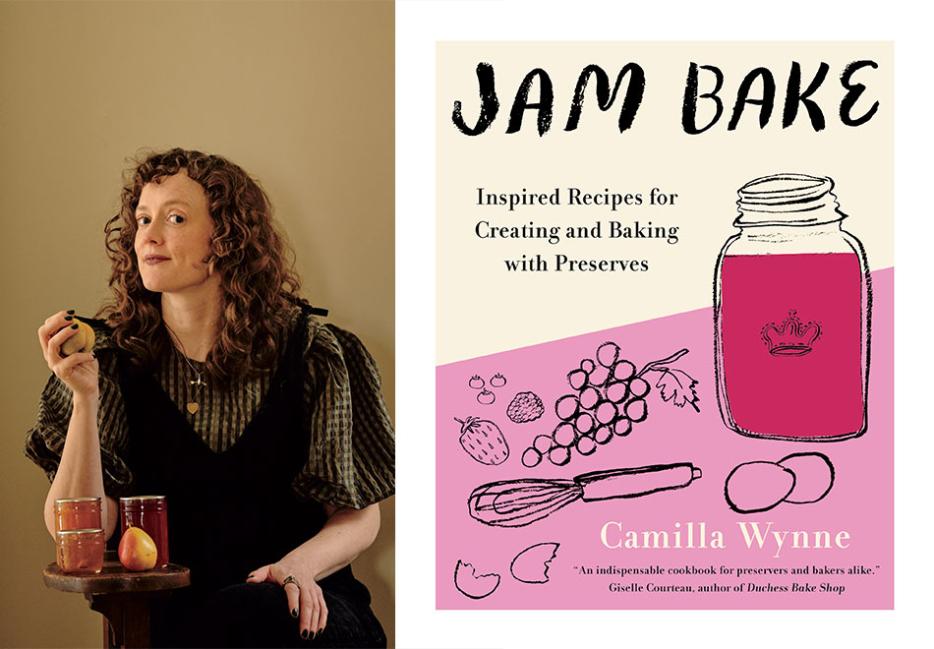

Through the most locked-down periods of the pandemic, I have felt cinched by my own routines, with only brief hours of darkness to peel apart the mille-feuille of same-o. Like many of us, I took some comfort in the calming measures of the domestic: cooking, sewing, and frenzied bouts of cleaning. Now facing an Omicron-haunted winter, I return to my kitchen cupboards for escape, pawing through the hardened bags of brown sugar and exhausted cartons of baking soda. On the top shelf of the pantry where I keep coffee and tea—dusted with the fragrant debris of both—are two unopened mason jars, one cherry jelly and another of pink grapefruit marmalade. Both of these are gifts from Camilla Wynne, whom I met in the brief intersection of summer and freshly vaccinated, to discuss her (then) just-released book, Jam Bake (Appetite). I can’t bring myself to break the seal on these precious jars, which preserve fruit, and something else.

Some years ago I became transfixed by the elaborate cakes baked and decorated by Wynne, formerly of the Montreal-based jam company Preservation Society; a musician, pastry chef, teacher, and gentle hedonist whose mastery of what she calls “back-to-the-land” skills elevates the domestic to levels of fantasy like Graeme Base’s The Eleventh Hour and Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette. One such cake posted to her Instagram account features three extravagant tiers, laden with candied fruit—another of Wynne’s specialties.

In Jam Bake, Wynne brings her rare creativity to the masses, sharing endlessly adaptable preserve-oriented recipes and gorgeous photographs of the results. Not only about jams, jellies, and marmalades, the book also features splendid baked good recipes (kamut and poppy seed muffins with pink grapefruit and almond marmalade filling; gateau basque with coffee, date, and pear jam) in which you can inject your freshly made preserves if you don’t want to limit them to toast.

Last summer, Wynne invited me to her home to chat about Jam Bake, and to make sour cherry jelly in her charming Toronto kitchen—the jelly that now lives in my pantry. My first in-person interview in nearly two years, I felt utterly drunk on the pleasures of Wynne’s vibrant workspace and immense charm (which comes through in her recipes, too). Dressed in a periwinkle zebra-print dress and coordinating Jacquemus socks, Wynne walked me through the steps of jelly-making before taking me out to her flower and plant-filled balcony, where we discussed her incredibly varied career, safe canning techniques, dresses that look like cakes, and cakes that look like dresses.

Naomi Skwarna: What was your gateway to jam, jelly, and marmalade? And more generally, preserving?

Camilla Wynne: I’ve always loved sugar and fruit and was pretty obsessed with it as a kid—plus the confluence of my granny and my aunt’s homemade jelly and jam. It had an air of mystery because we never made it at my house. I was the city slicker and then there were all my country cousins. When I started working in pastry, there was something so compelling about preserving because of its shelf life. [In pastry], we made so many things that were only good for that day, and so I was intrigued by the idea of being able to prolong the lifespan of all of these fruits that I loved.

Then, when I left working in kitchens to go on tour with my band, I would get so upset every time we’d tour during sour cherry season! So when I was home, I started squirreling away all those flavours to enjoy later on.

A flavour collection.

Yeah! A flavour library.

Preserving does seem like an effective way of extending the life of something that is otherwise sort of ephemeral. Since you were self-instructing, did you ever make any big mistakes, or was it pretty smooth sailing from the start?

I think any of my errors have been eclipsed by stories from my students about their seriously crazy mistakes. For instance: I have never given my friends botulism. A student of mine once announced, “I’m here at this pickling class because last year I gave all my friends botulism.”

You’re extremely clear about canning safely in the book—I mean, you do put a lot of time and clarity into ensuring that people don’t make those mistakes—but the pickling section definitely struck a bit of fear in my heart.

Thank you! I was self-taught at the beginning and I was so frustrated about this hard line North American National Center for Home Food Preservation thing that basically says anything that’s not this is danger! But then I’d read a book from France or England and they’d say, “close the jars and turn them upside down.” I was like, are they dying in droves over there?

There are lots of ways to can safely. When I teach, I show you how to work safely in what I think is the easiest and the fastest way, because I always want more time to read novels. Yes, there are a lot of bad, scary ways to can, but I teach how to discern the difference. If you understand the principles, you can objectively look at a method and tell that’s not safe. If you’re just following a set of instructions, you’ll either be a hard liner, or else you’ll just follow whatever instructions come your way, be they safe or not. It’s extremely important to my teaching philosophy for people to understand why, because I found it so hard to get anyone to tell me how it really works.

Well, props to your student for giving all their friends botulism and still wanting to learn how to do it.

He was a very enthusiastic 23-year-old man. Good for you, sir, but also: wow.

Will his friends ever eat something he preserves again?

I wouldn’t, personally!

Coming back to your training—you’re one of Canada’s only Master Preservers. What does that process entail?

It’s a lot less fancy than it sounds—it’s just not a program offered in Canada. I wish it were, because I think it’s extremely valuable. The idea is that universities, Cornell in my case, have extension co-ops in agricultural communities for the university to be able to disseminate their research to the farmers. So they have these programs to become a Master Preserver or a Master Gardener, where people learn to be experts at, well, “expert,” you know, through a five-day course. But we learn enough that we can then teach other people how to safely preserve. It covers freezing, pressure canning, hot water bath canning, and drying. Then basically, there’s a test, plus completing a certain number of hours of teaching or writing about preserving methods to show that you thoroughly understand the methods. It was so nice and great, but they also literally made us chant “canning is not creative cooking,” and my whole thing is that that’s not true if you understand [the science].

Reading your book, creativity feels like such a defining feature of your recipes and aesthetic. What does creativity mean in what you make and how you teach?

Sometimes I’ll ask my students, “Who else here feels if they can’t be creative, they’ll die?" And everyone will be like: (stares blankly). Maybe one person will say, “okay.”

I consider myself a cook as well. There’s such a dichotomy between cooking and pastry, but I cook a lot and I write a lot of savory recipes, too. I hope I don’t spend my whole career pigeonholed as only making sweets. In the end, it’s all making something with your hands that tastes good.

When did you start teaching?

I began in 2011 because of my friend Natasha Pickowicz, who’s a famous New York pastry chef now. She was working at the Depanneur in Montreal and was always organizing events; she’s a real organizer.

And now you teach so many classes! Your candied fruit is really breathtaking, and such a unique skill to offer a class for. How do people respond to it?

That class was so popular in the winter, I think partly because everything was locked down and no one I know has ever seen a class like that offered before. I couldn’t believe it! I thought no one was going to come, but it was my best-selling class for sure.

Those fruits are so gorgeous.

Right. I know. They’re so beautiful.

You mention that dichotomy in Jam Bake, too. It reminds me of what you said earlier about being a pastry chef and preserver—that the pastries you made were meant to be eaten straight away—

Yes, I don’t want to see a croissant more than two hours after it came out of the oven. They’re like those insects that only live for one day.

It’s like your work is split between making delicacies with brief lives and ones that can live for very long time.

And then the bridge there is fruitcake!

You’ve found so many outlets for your skills—as a pastry chef, writer, teacher, and through running a business. But it seems now that you’re very much your own boss. What are some of the challenges faced by someone who wants to work the way you do in the food industry?

Restaurants, which is where I worked, are their own whole thing, and we all started to see how highly problematic they are over the past couple of years. Pastry chefs, particularly, are paid less, appreciated less, and are the first to go when layoffs need to be made. Dessert is always considered optional and pastry chefs dispensable.

But, arguably, fine dining is about celebration, you know? And that’s exactly what desserts are for. Sometimes I get insecure about internalizing the idea that desserts are superfluous and I’m not doing it to help anyone. But pleasure is important, you know? It makes life nice. I have to remind myself of that frequently, especially being in a relationship with someone who literally keeps people alive [Wynne’s partner is an anesthesiology resident]. You’re like, sure, and I give you cake!

There’s pleasure in the making and in the receiving of cake! And a lot of your cakes in particular are some of the most stunning, sculptural things I’ve ever seen.

Thank you. I obviously don’t post the ones that aren’t...[laughter]

That’s every artist’s prerogative. What inspires your creativity, outside of the cooking world?

Definitely clothes! I spend a lot of time looking at clothes I’ll never afford. Lately a lot of them look like fancy cakes.

That is very true. Molly Goddard—

Yeah. And Cecilie Bahnsen. All the ruffles?

Ok, so I wanted to ask you—we’re still in the pandemic, but moving into a different phase of it. You mention in Jam Bake that making preserves has brought a lot of joy into your life. Can you talk about that joy, or the mental state this type of tactile, sweetie treat creativity cultivates in you, and what you think others can get out of it?

Even though I was highly inconvenienced by jars being out of stock everywhere last year when I was starting my online classes, I also couldn’t deny how awesome it was. I love that people are taking this up, because I do think it’s so full! There’s the kind of meditative pleasure of the act itself and then the wellbeing of a stocked pantry. It really makes you think, like, maybe it makes sense during these apocalyptic times to have weird, back-to-the-land skills.

Being able to eat well throughout all this must have been a real source of comfort.

The act itself brings the same sense of relaxation as yoga, I find. And I think it’s unfortunate that a lot of people are nervous about canning or cooking if they haven’t done it before. If they could instead just take a breath and think: I’m just observing this thing and I know what to look for. I’m not asking anything of it. I’m entering into a dialogue with this pot. We don’t speak the same language, but maybe it can tell me when it’s ready.

It’s like trying to see if a baby’s hungry. When you bake a cake, you can’t really watch it rise. It’s quite a quick process—maximum twenty minutes—but you have to be there. You can be checked out and maybe it’ll work, but also you might burn it. If you’re really there and just appreciating the serenity of observing transformation, then you’re probably going to do a better job. It just, I don’t know, unclenches something. I think it’s so nice.

Yeah, I can see that.

Wasn’t it thrilling when we saw those cherries transform from liquid to a solid? That’s why I call it alchemical. I know that’s just science, actually. It’s called transformation of states.

We don’t really experience a lot of obvious transformation in our everyday lives.

There’s the maillard effect—cooking, browning. But that’s more routine, as things we see every day. But making jam, it’s really special to see. It feels magic and if you’re not willing to experience the magic of things, well, that’s not fun for life.

Beyond the actual making of beautiful jams, jellies, marmalades, and cakes, what’s the most fulfilling type of project for you?

The satisfaction of writing a well-written recipe, and also making something taste good. I really have realized over the past couple of years that writing and making recipes is my absolute favorite thing. I also love teaching and I never want to stop doing that, but if I could manage to make a living by writing and making recipes? That would be certainly the dream for this guy. I have a pretty fleshed-out idea for my next book, so hopefully I can start concentrating more on that, getting it sold.

What will it be about?

It’s a candied fruit book! There are just so many different techniques to explore and then there are so many things to bake that are traditionally made with candied fruit, plus cool ideas for the syrup. I just think it’s a very rich topic—and I guess I will have to see who I can convince to agree with me.

[At this point in the interview, Wynne proceeds to lead me through a jelly tasting. Having told her earlier that I didn’t like jelly, she is now intent on turning me around].

That was so good. Tasting those flavours [damson, redcurrant, cherry,]—I am now a jelly convert.

My work here? It’s done.

I didn’t hate jelly, I just didn’t know jelly.

She was a mystery.