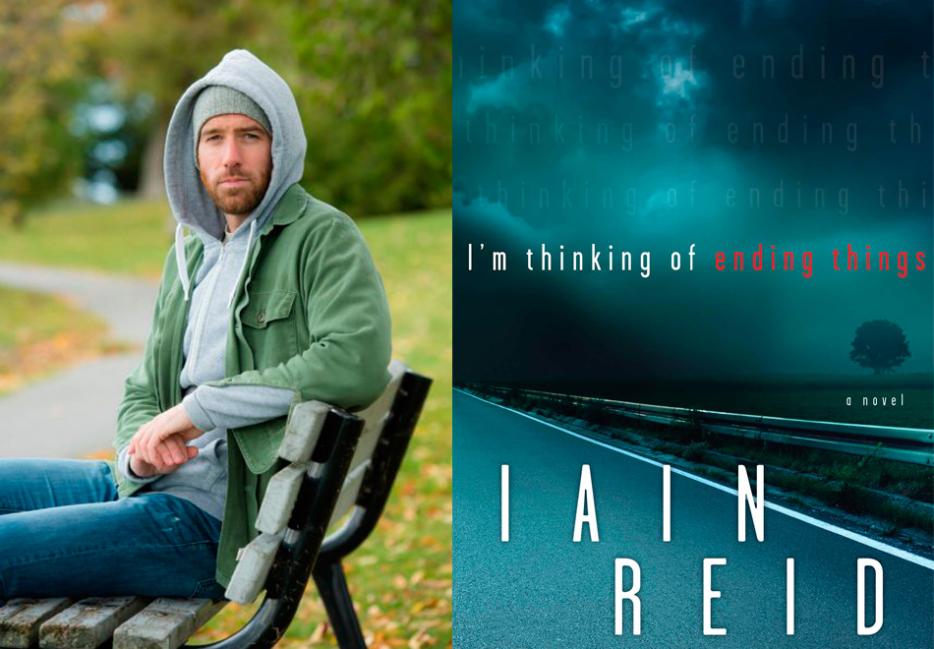

I picked up I’m Thinking of Ending Things one afternoon this past summer at a bookstore outside a movie theatre, planning to read the first chapter or so before my matinee started. Two and a half hours later, I’d missed the film entirely, although the experience of reading Iain Reid’s debut novel—his first nominally fictional work following the well-received memoirs One Bird’s Choice and The Truth About Luck—is akin to movie-going. It’s written to be consumed in a single sitting, where its fleet, headlong sense of dread can catch up to and overtake one’s expectations.

Narrated by an unnamed young woman on a (fateful?) car ride into the Ontario wilderness with her not-so-new-but-not-yet-forever boyfriend, the book toys with generic tropes of childhood nightmares—mysterious phone calls; a cabin in the woods—without compromising the uncannily credible subjectivity of its protagonist. Although Reid’s technique is not overtly Surrealist, his ability to selectively shift, blur, and then obliterate the line between literal and figurative borders on the Lynchian: given the road-trip set-up, a good alternate title could have been Lost Highway.

Like a lot of books that swivel on a pivotal piece of narrative gamesmanship, I’m Thinking of Ending Things is tricky to discuss in detail, a fact that was not lost on Reid when he agreed to do the interview below. But the book’s style and themes are so bound up in its surprises—and vice versa—that to completely talk around its twists would be futile. Suffice it to say that there is sufficient skill and pleasure in Reid’s writing that it’s possible to enjoy I’m Thinking of Ending Things even with a premonitory inkling of where it’s going, starting with that calculatedly ambiguous title, which doubles as an opening line and puts us in mind of a climax even before things have gotten started. It’s a cliché to say that a satisfying thriller demands to be read again, but Reid’s book actually goes ahead and demands it. It’s like a great midnight movie that turns into its own double bill.

Adam Nayman: Your book has been very nicely reviewed so far. Have you been following its reception very closely?

Iain Reid: I was uncertain what to expect, since it’s my first novel, and it’s sort of a weird novel. I couldn’t predict that people would be interested. I hoped that it would cause discussion, and a variety of reactions, and I think that’s happened. I’ve tried not to read reviews, because it can be frustrating. That’s my personality: it’s best if I don’t read the reviews. It’s also very tempting. I’m happy that people have taken an interest. I’m appreciative that people take the time to read it.

I guess there’s usually more attention paid to novels than memoirs, and bigger commercial potential as well.

I think that’s true in my case. I read more fiction than anything else. From the time I became a reader I’ve been drawn mostly to novels. When I started to write, I found it hard to do fiction, and I wrote a lot of it on my own. I ended up doing non-fiction to start, writing about my own life and experience. It was easier. It felt like I was starting a race when I was a little further ahead. I didn’t have to make things up, I was just reacting. I could just recall details and then try to shape them.

Is there really a hard line between this book and your memoirs? I mean, this book isn’t “real” but there are details in it that feel extremely personal, or else observed from a personal perspective.

The starting point for me in a novel is that anything can happen. I knew what I wanted to write about, but it was slow to get going. I don’t write from an outline. I like that anything can happen, and when I started, it felt similar to the other books—an extension or a progression. Then it got more complex. What surprised me was just how personal it became. The plot is made up; in a lot of ways, though, it feels more personal than the books I wrote about my life. I thought that by writing a novel there would be this screen between it and me, and there would be more privacy. But my first two books aren’t that revealing. In a memoir you take specific stuff you like and leave the rest out. You’re keeping things hidden. With this novel, suddenly all these ideas that concerned me and unsettled me were right there, and I spent several years thinking about them and working them out for myself.

It’s interesting, because often the joy of genre fiction is the impersonality of it all—the use of devices and archetypes, the satisfaction of having pieces snap into place. There’s a sense of structure and engineering in I’m Thinking of Ending Things that I responded to even as I suspected that it was a bit of a feint.

I read a lot of genre stuff, thrillers and horror novels. I appreciate their pleasures, and in the same way you described. I wanted to offer that stuff in a new way. I think form can be unsettling, beyond plot. Some readers might want to throw it away because of how it’s frustrating or how it withholds. Booksellers and publishers need to put something in a spot in a book store, or in a category. I worried that that might be limiting for this book. I was concerned about all that. The people who work on your behalf—whose job it is to market your book—I appreciate it very much. My loyalty always lies with the book, though. I tried to think of it as a good problem to have, that people would want to market the book in the first place, even if it’s hard to fit it into a category.

It’s hard to talk about the book without getting into the surprises, although I think the opening line is sort of coy, and sort of a clue. “I’m thinking of ending things” can be read a lot of ways, including as an invitation to imagine where things might be going even before they’ve begun…

I also wanted to emphasize “thinking.” It’s a big part of the story. The meaning of that phrase does change over the course of the book—not just the word “ending” but also “thinking.” There are different emphases as the story goes along.

I feel like if a book plays fair and pays off, then discussing “spoilers” should be okay in interviews, but it’s also important to preserve the excitement for potential readers, so let’s try not to.

I’ve been doing events and readings and people want to talk about their reaction to the ending. It was important to me that it’s open to interpretation. I have my own ideas about the ending and what it means, and I’ve heard a variety of other readings as well. I like that. It’s not up to me. I wrote it, and I have my take, but if someone takes the time to read it, and to think about it, their interpretation is totally valid. That’s how it differs from a lot of other horror novels, which have a more objective goal, moving from A to B.

There’s a difference, I find, between works that arrive at something ambiguous and those that set out for it in the first place. I didn’t think your book was the latter…

As a reader, or as a viewer of movies, I like to know nothing going in. It’s a more interesting way to start. It doesn’t always matter, but if I don’t know the plot at all, that’s great, and that’s rare.

There’s a better chance of not knowing anything about a book if it’s obscure or unsuccessful, so that’s not exactly what you’re hoping for here…

I felt bad for the editors when we were trying to figure out the jacket copy for this book. The Canadian edition only has blurbs on the back, and I liked that. That made sense. Instead of a description, it’s just quotations, and impressions from people who’ve read it, and that offers enough.

I thought there was this wonderful balance of concreteness and abstraction in I’m Thinking of Ending Things.

Thought versus action.

And also literal versus figurative. I respond well to books and movies that obliterate that binary.

One movie I saw that I knew very little about going in—and had no real expectations for—was that Denis Villeneuve movie Enemy. I think it’s a polarizing film. After I watched it, I wanted to watch it again, immediately.

Funny you should mention Enemy, which in its way is about how people present themselves in relationships, not unlike your book.

When I started watching it, I was worried that it was the same thing as my book. It turned out not to be, of course. There were similarities. I was transfixed by it. The ending was brilliant, and I’ve never seen anything quite like it. It’s not meant to be put together like a puzzle, or like an Agatha Christie book. It’s much more about this feeling you have when you’re watching it. And all the Toronto stuff is very interesting to me, because when I lived in the city, I lived in St. James Town, and I know all those places, those apartment buildings.

Most movies about Toronto don’t face in that direction, you could say. I think the film was originally going to be shot in São Paulo.

Enemy is also an example of a movie being very different from the book it’s based on. There’s a cliché that book is always better, which is silly. They’re two different mediums, and they’re inherently different things. The more different they are, the better it can be for the book, and for the movie. Another one that comes to mind is Under the Skin. The movie is totally its own thing. I love the novel, so I was interested in the movie, and I liked that it didn’t just try to film the story. It’s very much its own entity. Another movie that had an ending that intrigued me was Cache. When it ended, I felt like I could interpret it several ways. For some people that’s frustrating. For me, it was exciting.

There’s a very unique sort of terror in the book, which is the anxiety and insecurity that attends the beginning period of a romantic relationship—or if not the beginning, the part just after the beginning. The early-middle, maybe.

I really do think that’s the main thing, which is that area of a relationship. We often see relationships crumbling, or else we see the very beginning. This other period is very significant though. Like when you are comfortable to go on a road trip for the first time. You know the other person, but then you think about it and maybe you don’t know them very well at all. If you go on a date, and then two dates, and you’ve slept together, you can feel an intimacy, and it’s intense. It can offer a feeling that’s more secure than actually is the case. It takes a long time to get to really know somebody. That early stage, with these intense feelings, and the beginning of that confidence, can be misleading. I thought that writing about that, and then setting in a car, would work because it’s an enclosed space, and that heightens everything.

The narrator is very conscious of her boyfriend’s traits, and she sort of starts to see herself through his eyes as she’s revealing more and more about him. The book has one narrator, but it’s a dual character study, in a way.

That when she’s at her best. People think about themselves in that situation. “How am I being perceived by this other person?” You’re super aware of that, much more than when you’re alone or if you haven’t been in a relationship for a while. Then suddenly you are, and everything—your actions, your posture, the way you eat, how you smell… you’re thinking about all of those things. How is the other person experiencing all of that? Is it positive or negative? All of that.

The car is one crucial space in the book, and there’s also—spoiler alert—a cabin in the woods, which is a bit of a cliché, especially in Canadian fiction. Is there something self-conscious in that choice?

I think there is—that was something I was aware of. You do come across it a lot. I also think that it works. It seemed relevant. If this is a personal story, it’s also that that was my experience. My life has been much more rural than urban. I lived in Toronto for four years, and that’s my only urban experience. I grew up on a farm and I spent time there after I studied at university, when I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I was back there for a year. This book started during that time, with the feelings I had then, which were part of the landscape and the environment. It is isolated, and while I appreciate that environment, the isolation is definitely heightened. The story fit into that. Also, while it’s true [about it being a trope], a lot of contemporary fiction—maybe not in Canada—there is a trend towards urban stuff, in New York. Writers who live in Brooklyn set their work there.

Where I got very creeped out was in the description of the high school, though. I can’t think of anything scarier than being trapped there, not literally, but the idea of being on the edge of adolescence and adulthood at the same time, and not being able to get out. It’s very overwhelming, and upsetting.

That’s how I felt, and that’s why I picked it. There were multiple areas or settings I had in mind, and I went through them and that one came to me and it had to be that. The school had to be part of the book. A school at night, in that sort of area, isolated and hard to get to. It was terrifying for me, too. As a writer, that’s how you have to go about it. You have to use your experience as a reader. I know how I would have felt reading about that, and it would have scared me. The thing about high school is you’re constantly around people, but not necessarily feeling connected. That idea of human presence, to an overwhelming point, combined with overwhelming feelings of isolation and loneliness, I think is unique to high school.

I think there’s a really interesting relationship between the outer shape of that scenario—trapped in an empty high school at night—and some inner fear that’s beyond the simply generic.

A lot of high schools have these long, rambling halls that you can’t see the end of. You get to the end and there’s another one. There’s this physical feeling of oppression. Each time you think you’ve gotten through there’s this new set of issues.

Would you say the school is where the style of the book starts to, if not break down, then mutate into something new? It’s subtle but significant.

I hope that it’s noticeable, even if it’s subconscious. You can detect the change, but maybe not intellectually, at first. If you’re aware of it in the back of your mind, it can be unsettling. There definitely is a change, though. The beginning in the car is essentially a philosophical dialogue. I’m using that technique to work through certain concepts and ideas, and then there is a shift away from that.

This is a tricky thing to bring up, but one of the things you do in the book—to an extent, and also in a way that’s ultimately calculated and controlled—is get inside a female subjectivity. You’re not the first male writer to do it and you won’t be the last to try, but it seems worth bringing up and discussing…

I was aware of that. I wrote two books about my experience, as memoir, and I didn’t want to do that anymore. I wanted to something that would be difficult, or challenging. It was. It’s not up to me to say whether or not it was successful. If somebody doesn’t think it works, or that it’s believable, I would never question them on it. As a writer I want to try to write from different perspectives, which is the whole point—to put yourself in somebody else’s position.

It’s a complex issue, and it’s made even more complex depending on how one interprets the book—and the question of subjectivity. I feel like there’s an amazing tension there.

I think the story is about writing. I talked about that with my editors a lot. It was about the experience of writing, and how you give yourself over to something and it starts to become real to you, in a very serious way. It’s about that process and what that process is like. With this kind of book, people will project their own ideas about things onto it.

Because you leave them a lot of space to do that.

Yes. I’ve read certain reviews that are more about the reviewer than they are about the book. That’s interesting to me. That’s part of writing a book. You put it out there and people are going to react to it in the way that they see fit. I plan to keep writing about things that are difficult for me, and which I may not be able to do, but I hope to try.

How long did you spend on the book?

It’s hard to say. I was writing it for about three years, but some of these thoughts were around long before that.

I’m thinking of ending things now: what’s the first image that came to you before writing?

Probably just country roads, and driving in the woods. It’s amazing how many people comment on the darkness of these roads far from Toronto. If you stop and turn your lights out it’s pitch dark. It’s quite jarring. The car lights illuminate, so it feels lit, but then you stop and you see how much darkness is there. That was what came to me first, knowing what that’s like. I’ve been on those roads in the middle of the night, and it’s a strange feeling if you’re not used to it. The character in the book—it’s all new to her.

Have you been with somebody experiencing that for the first time as well?

I have, yes. In fact, I talked to them about it. as I was working on this book. And I can recall someone saying, “You’d better stop talking about that, because you’re scaring me.”