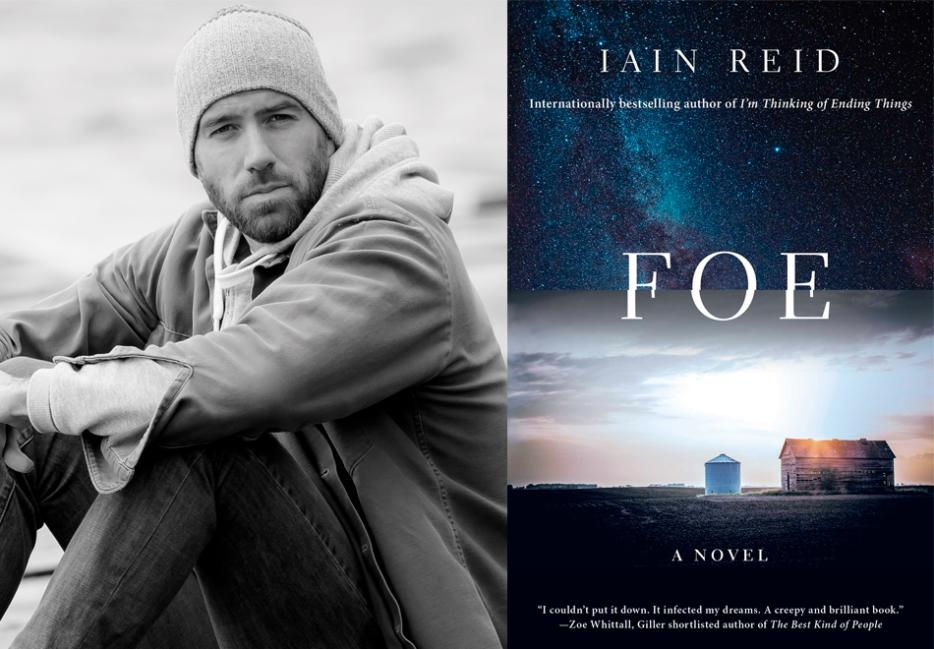

With his 2016 best-seller I’m Thinking of Ending Things and the new Foe, Iain Reid has made the middle of nowhere into home turf: his wary, watchful novels take place off the grid, both in terms of geography and genre. “We don’t get visitors. Never have. Not out here” says Foe’s narrator, Junior, a young farmer living somewhere in Ontario with his wife Henrietta. His tone suggests that the intrusion of a third party is as unwelcome as it is unexpected.

Junior’s anxiety is not misplaced. The visitor is a figure out of an X-Files episode, a proverbial Man in Black claiming to represent a government-funded initiative to relocate Earth’s swelling population to outer space. (“This is a long time coming.”) What’s more, the man, whose name is Terrance, explains that Junior has been selected by lottery as a possible candidate to join the off-world workforce. If his number comes up, choice is not a factor; he cannot decline the call of duty. Service is mandatory. But—and this is where the outsider’s spiel truly starts to seem strange and sinister—arrangements can be made if Hen needs somebody who looks and acts a lot like her husband to take care of her.

The pleasure of Reid’s work—and he’s as gifted and scarifying a storyteller as Canadian fiction has produced in a long time—is how judiciously he parcels out narrative information. If I’m Thinking of Ending Things was a brilliant and resourceful variation on one of the oldest tricks in the mind-fuck-fiction handbook, Foe is similarly indebted to a science-fiction tradition encompassing Dick, Clarke and Asimov. These layers of reference are no more than a brilliant disguise, however, cloaking Reid’s true and universal subjects even as they lurk in plain view on every page.

Adam Nayman: It seems to me that the through-line between your two novels so far is isolation. In I'm Thinking of Ending Things, you have a young woman who becomes increasingly unnerved as her boyfriend takes her into the country and out of her urban comfort zone; it's sort of a journey away from the center. In Foe, you focus on a couple who already live on the margins of civilization in the middle of nowhere and are accustomed to it, until an outsider shows up. It's an interesting reversal, but there's also a continuity there.

Iain Reid: There definitely is that underlying current of isolation [in I'm Thinking of Ending Things] and it’s here as well. It does change a little bit for Foe, as you said, as the isolation here involves things that are familiar for the characters. At least at first, anyway. I think that isolation and solitude are the things that I started out with on this one. I always think of one or two major conflicts or problems when I'm getting going, and on Foe, they were isolation, solitude and confinement. “Confinement” was a word I was thinking of a lot in the early stages. I wanted to know what it was about confinement that I find so unsettling and disturbing, and it ended up going down the path of relationships and marriages. If you've been told for your entire life that you should feel a certain way about something—that you'll like something, or dislike it—you start to believe it. But what if something happens to make you start questioning that attitude? That's sort of what Foe is for me in a lot of ways.

I also noticed that Foe begins with the image of headlights in the dark, which is pretty central to I'm Thinking of Ending Things. We talked about that image at the end of our last interview, so maybe it's a fun way to get into the new one.

That’s the opening image of the book exactly, yes, and it was absolutely one of the first images that came to mind for Foe too. But the thing that really influenced me before I started writing was this: I was out at an awards ceremony and there was a man who was receiving a prize and the way he thanked his wife from the stage was very disturbing, at least to me. Everyone else was really happy with it, and they thought it was this great acceptance speech; they were almost sighing out loud at how it was. He said things like “I want to thank my wife for putting up with my instability, and allowing me to do what I do.” I thought, “No, I'm sure she has her own thing, her own life, she's not there to prop your genius up.” It seemed so icky to me, as did the idea that this dynamic was something he was being accepted or even congratulated for. So that's when that idea I mentioned before about confinement within a relationship came to me. I wanted to write about a relationship that wasn't ruined by one dramatic moment, like somebody cheating or losing their temper or a secret, but instead had been slowly rotting over time. Once you're in a situation and you're committed to it, what else can happen? How can you get out? That's where things started.

Let's talk about how a lot of people are going to come to Foe, which is not only in light of I'm Thinking of Ending Things but also via genre: it's being marketed as science-fiction and the genre stuff is present alongside the portrait of the marriage. And it gets into the sci-fi stuff pretty quickly, so much so that I was surprised. It's very disarming when Terrance shows up and provides all this exposition about the possibility of colonizing outer space to a couple who seem to be living this out-of-time existence in the country.

I think I had it in my mind for a long time that I wanted to write a novel about space, to have some type of element about space. And the reason for that is that my brother is a rocket scientist, and he works in that world. So whenever we would be together, the conversation would always evolve or devolve, depending on your perspective, to me peppering him with questions about space travel, and where it's at and where it could go from here, It's fascinating for me, as somebody who has probably a fairly average knowledge of that industry, to learn what it might look like in ten or twenty years. My brother is the kind of person who if you go see a science-fiction movie with him, or a movie about space-travel, he'll pick them apart. So I always thought he'd be a great resource in ensuring that what I was doing was authentic. So going back to the idea of confinement, what is the opposite of that? Space. So I also realized this would be my book about space. I talked to my brother a lot while I was writing but then he read it and he said, “It's not really about space.” Part of that is that I took a lot of things out during revisions, to the point that the outer-space aspect is more of a metaphor than anything else.

Science-fiction is always really conducive to metaphor, and in that sense Foe felt a bit old-fashioned to me—almost nostalgic even though it's set in the future. There's a really slippery sense of time throughout, actually; there's very little about Junior and Hen's lifestyle that wouldn't have been more or less identical if they were living in the same place in the 1960s. It felt like I could have been reading a book about two people in 1969 who suddenly learn that there's a Space Race going on between America and the Soviet Union.

You’re right to think about the initial moon landing. That was on my mind, too. What would happen if an ordinary person had a chance to be a part of that? If somebody showed up at their house with this mission and this invitation, how would it play out?

It's also really effective how you suggest that the world has changed around them in some big ways but they haven't even tried to keep up. There's no reference to technology, social media, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, even though all those things will likely be around in the near future, if not amplified...

That's the timeless element we were discussing earlier. I think there is a dynamic to their marriage that's closer to the 1950s or 1960s. There's this assumption that things have changed a lot since then, but I think that restrictive element is still there in some places, including some rural settings.

That places things right on the fault lines of some of the larger culture war stuff that's going on now in Ontario and of course in the United States, too. That's not to generalize about “small town values,” because I think those liberal clichés about them can be as reductive and reactionary as the values themselves. But I did feel like Junior and Hen's marriage was suggestive of something larger and older that's also cyclical and maybe inescapable. I mean, Junior could not be a more patriarchal name, right?

That’s exactly right. And if you think about sort of what happens in the triangular relationship between Junior and Henrietta and Terrence there’s a shift along those same lines. There is a change that Henrietta goes through, as does Terrence. I think Terrance changes too. Really, the only one that doesn’t change is Junior.

Hen’s pretty suggestive as a name too.

Ha, yes. Junior talks about them having chickens and how he goes out to feed them and care for them. He also likes it when Hen plays the piano for him...

Junior reveals a lot of things by accident; he's not just an unreliable narrator but he doesn't seem to necessarily know his own mind all that well either. In I'm Thinking of Ending Things your narrator had a huge amount of self-awareness, and kept throwing up all these defense mechanisms and checks and balances. I feel like Junior is transparent, and that makes him a unique entry point into a narrative where all is not as it seems— especially not to him, we could say.

In this type of marriage, who would be the one who would be permitted to speak for both parties a lot of the time? It would be Junior. He would be the filter that their communal story would be told through. That also I think was part of Henrietta's wanting a change, as she begins to wonder what's best for her, to assert herself, and to take some power back. I was thinking a lot about toughness when it came to her character. Normally if you say that one of your themes is “toughness” people will assume it's a story about boxing or something; I wanted to access toughness in a different way. You've probably heard people talk about a basketball player like Manu Ginobili and how he plays “in between the dribbles,” and I like stories that do that too. So when Junior is telling us things, he's also giving us more than he's saying, and maybe some of it is about Henrietta, more than he even knows.

It's funny because, while he gets a lot right about Henrietta and even how she feels about him, he really doesn't know what's going on with Terrance; his suspicion and jealousy become misplaced in a way that's very alpha-male macho and sort of naive at the same time.

Yes, exactly, and I think that when I was reflecting on how a marriage like this might disintegrate, that's sort of how it would happen, with the intrusion of a third party, whatever the third party is actually trying to do in the end. Trying to reflect on a way that this relationship is disintegrating in the way that I envisioned, that’s sort of how it would happen. I think that when these people got married they thought that it was love and that it would last a lifetime, but I don't see how that can work if you think of yourself first. This seems like a common thing, actually, that from the male point of view you get married and you're sort of “done.” It's like getting a job or something—you just check off the box and you're married and that's all. That's a horrifying thought from both perspectives, I think: that marriage is a thing to do instead of a process that requires work and effort and change from both parties. The idea that you just take comfort from the fact that you're married, you're in it, and that's it… that's horrific to me.

Well, not only that, but culturally we’re conditioned to think that the stubbornness and the laziness of men—and to some extent the flaws of both genders in heterosexual relationships—is “cute.” And then it hardens over time, and any complaints about it are met with truisms like, “Well, you're married, that's how it is.” It's like the idea of “letting yourself go” but not just your body; your sensitivity and your curiosity, too. Junior hasn't let himself go physically, though, and there's a frightening quality to how he describes his own body and his strength—it turns the narrator of the story into a potential source of threat even as he's growing paranoid about what's going on behind his back.

It is frightening, I agree. And again, if you think about it in the context of confinement, or the opposite of space, and that physicality that Junior has...Again speaking about metaphors, I think for me what seemed enticing about a story like this right now, again I don’t think I’ve really talked about this yet and I don’t know how much I will, but sort of what’s happening in the world right now, in the western world, politically, ending up stuck with someone strong and scary like that... it's not a joke, it's not charming, it's quite horrific. You're stuck with that.

Are you married yourself?

No, I’m not. I know that you are. It's funny because marriage is such a clear interest of mine.

No kidding.

Yeah, and it’s funny, because I have been asked, it must be because people think I’m anti-marriage because of these books and I’m really not, in fact I’m the opposite. I think that marriage is wonderful and I can see how it would be very appealing in certain situations. I would say that I might be married at some point, who knows? I’m not anti-marriage, I just find the idea of it utterly fascinating. We do it in such huge numbers, and so many people do it in such a way that’s sort of like passive acceptance. And yet it seems like the hardest thing you can do. Even having kids, that’s more purely biological right? That you have this desire to protect your children? But to live with one person for your whole life, and the inherent challenges in that... so many people want to do it, or think they want to do it or don’t want to do it, or don’t think about it at all. They just do it. Maybe that's indicative of why the divorce rates are over 50 percent now. And then if you take into account those couples who aren’t divorced, how many are struggling in a very serious way?

That notion of being trapped in a marriage because there's no language to even discuss separation evokes the frontier—it evokes the past. But I agree with you that it's no less of an issue now.

I think that if I were to write a story about a serial killer chasing somebody, I'd be interested on how the person being chased would try to escape—all the ways available to get out of that situation. I think that's what I was thinking about, actually, in a different context. Foe is a more quiet kind of horror.

Did you have fun coming up with all the gimmicky sci-fi stuff? Terrance's stories about his company and their experiments in 3-D printing and replication are quite outlandish but he keeps rooting them in science and it's quite funny, but there's also the possibility—broached by Junior and passed on to us—that Terrance is just full of shit, or crazy, or making the whole thing up.

It's funny because that’s the one part of Foe that, when I look back at it—at some of what Terrance says, and how he says it—that makes me laugh a bit. At the same time, he's a character who contains the possibility that anything can happen at any time, which heightens urgency and suspense and tension. It's a balancing act to be as delicate as possible, and the more you try to explain, the weaker the material gets. If I let a reader imagine what's happening—and maybe wonder about a character like Terrance—it's so much better, because then it lives in their imagination.

I feel like Terrance and his story are effective because Junior is so out of the loop. If he lived in a city and had a smartphone and a Twitter feed and a bunch of friends, the ambiguity would be gone. He sort of has to go on what he's being told...

Exactly, which goes back to you talking about isolation at the beginning. That's why it works.

Well, now that we've worked our way back to the beginning, let's end by talking about the fact that I'm Thinking of Ending Things is being turned into a Netflix movie by Charlie Kaufman. I wonder if that last sentence is surreal enough that you just want to sort of talk about it?

Yeah. It's been a great experience so far, because it was so unexpected. The last time we talked we discussed how interior I'm Thinking of Ending Things is and how impossible it would be to adapt into a film. A movie version was never in my mind, but if I could have picked anybody to do it I would have said Charlie Kaufman. So it was an unbelievable surprise that he had interest. I've been really happy with everything so far and Charlie has been so nice and kind and generous. At this stage it's still in development and I'm excited to see the final version and how it turns out.