The first and last books of the Bible report that creation began with the sea and will end there, too. The opening line of Genesis reads, “darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters.” When God sees fit to add more substance to creation, he prioritizes light and sky over land and, as most know, doesn’t get to humans until his last day of work. God populated the land with animals on the fifth day, but there is nothing about God populating the seas. Perhaps it was an editorial oversight. Perhaps someone besides God populated the sea. I am neither a biblical literalist nor a believer but the omission of the sea’s population from the creation story never sat right with me. The ancients who wrote it were hardly marine biologists but surely they saw something of significance lay in those ghastly depths.

I used to think that the sea was the primary threat, inching its tides deeper and deeper onto our shores and into our cities with every storm, each time bearing more acid with which to erode what we thought was indestructible. For a long time, I read malevolence into its grasping for more land. I read sinister intentions into every report of a rising tide. I mourned the loss of coastline not as a natural disaster but as a murder. But I didn’t yet know what malevolence over the land looked like. Though the scarce and prideful land is indeed in danger from climate catastrophes, the more imminent threat comes from those who seek preposterously to contain it, to make parcels of it into exclusive compounds rather than human refuges. Land that used to nourish us now divides us more deeply than ever. People will slice fractures into its soil and pump poison into its waters long before the ocean comes to claim it.

*

I was born in 1985 in Bethesda Naval Hospital. President Ronald Reagan happened to be on the premises getting medical care the day my mother’s labor started and I waited until 4 p.m. the day after he left. In my inclination to stay in the warm, wet confines of the womb, I visited complications and delays on my mother for over forty hours before emerging, grudgingly, and with a self-inflicted black eye. Family jokes endure that my refusal to keep company with Reagan was my first act of political resistance.

During his campaign the year before, Reagan had used Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” as his theme song, despite its antithetical message to his platform. Bruce Springsteen, still steaming from Reagan’s misuse of “Born in the USA,” began performing the song to return it to its rightful place in the resistance music canon. I learned the song in preschool, as many American children do. It is at once a critique of wealth disparities in America, a love letter to her landscapes and wonders, and a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it nod to Genesis. “This land was made for you and Me” is a creation story.

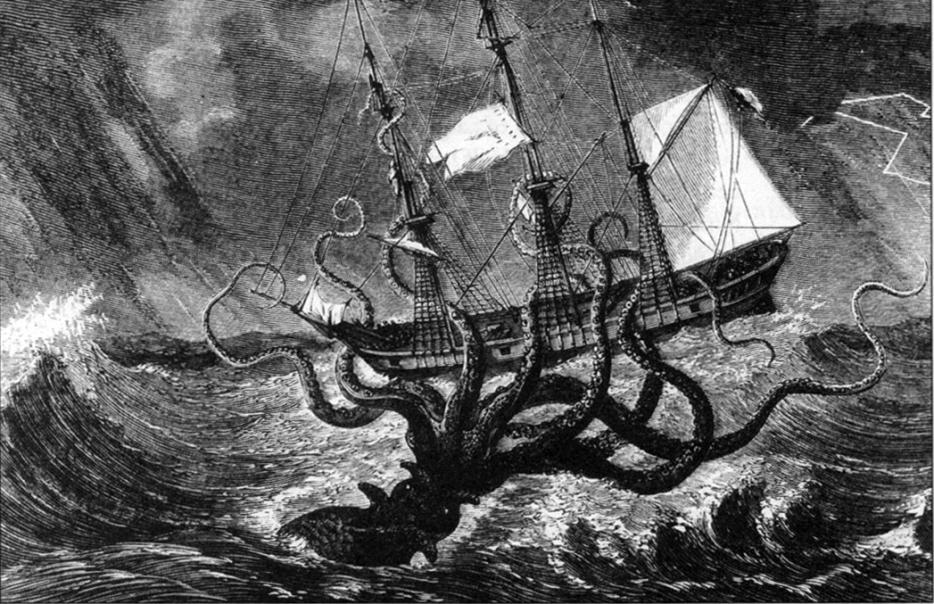

“From dust you came, and to dust you shall return” is another frequently repurposed refrain from Genesis, isolated so often from its context that many forget that this is not a description of human nature but a punishment for it. It is God’s decree to Adam and Eve that they shall toil and perish for their disobedience. It is the creation story of death itself. And death will come from the sea and be found on the land. The Book of Revelation reports that a seven-headed beast will emerge from the oceans and quickly be granted authority over a now depraved humanity by a dragon already waiting on shore. It is quite a flourish of interspecies political drama. Some believe that the seven-headed beast represents an octopus whose tentacles have been miscounted and will appear at the end, as those scoundrels often do, upside down with his multitude of muscular appendages on display, an executioner showing off his grand instruments of death. Another variation is that each head represents one of the seven continents of the Earth, the very land itself. If that is the case, we have not been waiting for the end times, but living them. If the continents represent a malevolent end, we have been part of that story all along. We think of the land that exists as a permanent fixture on this planet, but geology and the hints left by history tell us it is but a blip on the radar. The land emerged from the sea not entirely all that long ago in the grand scheme of things. And the sea is coming back for it.

I have long been afraid of the sea, despite plenty of reasons to love it and even show it gratitude. My parents were bright-eyed but likely stuck Arkansans when the impending Army recruitment that would send my father to the jungles of Vietnam was cleverly thwarted when he joined the Navy instead. Taking to the sea was my father’s passage away from the early death or elongated nightmare promised by the war. Living in cities near Navy bases but never on them gave me a childhood dense with sunsets, swimming, and the vague sense of worldliness conferred by the horizon’s confirmation that my country was not the whole world.

As a young teenager in San Diego, I was one of few girls to play on a co-ed water polo team. There was a ritual during which the team was cast into the Pacific for a week of grueling practice. The idea was that if we could keep afloat in the waves, we would surely dominate in the pool. The idea was correct. Though I felt like my legs might disintegrate at the end of each day, I am still a strong swimmer. I can tread water for hours.

The few girls on the team were close and we’d convene often for sleepovers. A frequent game was “Would you rather?” in which two unpleasant hypothetical scenarios were presented and you had to choose one at your turn. They usually included gruesome tasks involving refuse, blood, and horrible boys. But reliably, someone would always ask, “Would you rather burn to death or drown?” Everyone always chose to drown.

Nevertheless, I spent years of my life having nightmares about sea monsters. A particularly unpleasant and regularly recurring one featured a ten-foot-tall octopus barreling after me, easily felling trees with the chewy beef of his tentacles in his pursuit. He was a composite character, two distinct creatures rendered in what would now be considered rudimentary CGI in a 2002 documentary series called “The Future Is Wild.” The series was an exercise in speculative evolution that transfixed and terrified me with hypothetical future beasts. My mind combined the swampus, an octopus that has taken to the mostly flooded land of planet Earth and snaps the necks of giant tortoises for sport as much as for sustenance, and the megasquid, a hulking forest-bound squid descendant who bellows territorially and savages forests, his malevolence toward life forms on land still fresh even after 200 million years.

I realize that I will be long dead in far fewer than the several million years it will take for the sea monsters to hypothetically invade the land. But in place of the fear of sea monsters at my doorstep is a waking dread of a more upsetting fate. Not that an octopus will venture into my territory, but that I will be involuntary swallowed up into his. A common refrain in the octopus discourse is that if they ever develop vertebrae, they will compete with humans for dominance of the planet. What people mean is that they will compete for dominance of the land. They already dominate the planet.

*

“When Will New York Sink?” asks the early September headline of Andrew Rice’s investigative report in New York Magazine on the rapidly rising tides that will consume the island. “Too soon,” I had already answered eight months before when I resolved to leave the city I had called home since 2003. I read the headline and the story itself from a farmhouse in the Catskills. Despite knowing the losing prospect of land, I had just completed the purchase of the farmhouse the very same week. With the house came 1.5 acres of land and the promise of appreciating value, that charming term for future funds earned through idle patience. It sits 200 miles west of the Atlantic and 107 miles north of the inner edge of the Long Island Sound. But this is not the safety of higher ground so much as the bided time of a snooze alarm. The house also sits a stone’s throw from the Hudson River, which is not an ordinary river, but a tidal estuary, a benign sounding name for waterways that can flood and do flood far deeper than the coasts can currently hope to. My fixation on the fate of the land has rendered me no less susceptible to hollow promises of her immortality.

I spent the first two months of owning this land reveling at how much of it was mine. This land was bought for only me. But after the presidential election in November, my land took on a grotesque character: it tagged me as a stakeholder in something rotten, a hoarder of land in a country whose identity was always so wrapped up in the myth of its endless and impossible abundance. The land and the house that sits on it at once became heavy anchors to a country I might ideally flee and signals of a liberation that freed me to own and to isolate that are largely unshared by the rest of the world’s citizens. The small man occupying the big white house is a hoarder of lands too. Overnight he turned our land into a fortified bunker. It was this action that made me realize that my home need not be an instrument of torture in my various existential crises but a shelter from the coming tides and flames. I have since opened its doors to those whose lands have already rotted.

Many take heart in the belief that we have civilized and reasoned ourselves out of biblical fates, that one day soon, this president will come to whatever sense he might have and end this nonsense. I look to the walls, both real and imagined, in the works and see little chance of this. For how many times we forced ourselves to contemplate as girls whether we would burn or drown, we did not really consider what the actual cause of death would be. Our preoccupation was over the preference to be submerged in flames or in watery depths—it was a choice between pain and panic. We didn’t stop to think that at the end of the day, it’s suffocation that gets you in both cases. And this regime is already working to cut off the air from the outside.

But even if we do escape the Trump years with our breath, a scientific approach to how we might meet our end provides little more solace. To research the emergence of life on this planet is to bear witness to disaster, tumult, and cataclysmic change. Humans have christened these events with names befitting battles, golden ages, and scandalous dynasties. The Great Oxygenation Event. Abiogenesis. The Cambrian Explosion. These events were more exciting than they sound, and they already sound quite exciting. They also lasted longer than human life likely will. Much longer. They also tell us that the emergence of land was not an accident, per se, but they do point to something more temporary than the seas. We are owed back to the seas from which our ancestors came.

Whatever hubris it was that propelled that puddle-bound slime creature gasping onto the land, we have inherited it. We accept that human life springs forth not from desert sands or even the blackest forest soil, fat and wet with nutrients ready to serve life as we understand it. We emerge instead from the sticky broth of wombs, gingerly calling this bloody flood of a beginning “when the water breaks.” In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson described the placenta that emerges at human birth as “a bag of whale hearts.” New mothers are sometimes advised to eat it to restore the nutrients lost in gestation and birth. I cannot stop myself from straining the metaphor back into the deep: these whale hearts are mementos from home, coded into our reproductive processes to restore us to, and remind us of, what we once were.

I intend to carry such a bag of whale hearts inside me some day, maybe sooner rather than later. Perhaps even two of them. Three if I get what I actually want, a thing that tends to happen more often than any of us admits. I want children no matter how fashionable it becomes to proclaim one’s unfitness and disinterest in becoming a parent, a good thing considering the planet’s circumstances. I have heard procreation called selfish, read our species described as parasitic, and been told in no uncertain terms that much of the world will burn before the rest of it is left to drown. I want children because I feel called to it from the insides of my body, yes, but also because I want to witness some flicker of my own immortality, to see a study of eternity in helpless miniature.

When we chose as girls to drown instead of burn, we answered for what would actually happen to our bodies but we did not account for how we would find ourselves in a circumstance that would make these our options. To choose drowning or burning suggests that we might be given two discreet lethal processes by which to die, an option generally only afforded to those convicted of capital crimes and them with far less theatrical choices. These choices do not describe how we came to circumstances in which we might burn or drown. Might some have made it to higher ground after outrunning the rising tides only to find themselves at the peak of a volcano whose interior will burn them mercifully quick? In the now escalating fight for this rotting precious land, humans have fought unto the death, drowned in their own blood on their own land. Other have already found themselves at the bottom of the sea after they escaped their home cities aflame on the land, torched by the hands of their neighbors long before the rays of our sun could get them. Now their survivors come to our shores, and unlike Mr. Guthrie, somebody living can certainly make them turn back, away from this land made for you and me.

If we survive this, I wonder often how I will look my children in the eye and tell them that I knew long before they were born that they would one day have to burn or drown. I have played the scene over again many times in my head. But the most painful part is always a moment in which I want to reassure them of our safety in the event that the sea comes for the land, or if the land crumbles into it, or if another small man says this land is no longer for me and casts us out. In this moment, I pause before delivering my reassurance and then I stop myself. Not a child on Earth has ever been saved by the knowledge of how well their mother can swim.