Last year, one could hardly shake a metallic gold G-string at the internet without hitting a story about the feminism at the heart of Magic Mike XXL. This rowdy comedy about male strippers and the women they entertain might have been fodder for ridicule and summarily dismissed for its raunchy dance segments and endless dick jokes. But the friendships at the core of the film and the emphasis on the service these men provide to women elevated it to a peculiar cultural moment in which erotic labor and the bonds developed between men while performing it were celebrated as social progress. It joined a beloved cohort of films representing friendship dynamics between male sex workers, from the Oscar-winning Midnight Cowboy to the cult classic My Own Private Idaho. These are emotionally resonant films that pushed social and artistic boundaries by portraying the multiple dimensions of male sex workers’ lives and how their work informed their relationships with friends. These men do not require redemption narratives to earn our love. And these sex working men do not have to fall in love with anyone for these films to be love stories. They have earned their status as classics. But there’s a painful absence of similar films portraying friendship between female sex workers.

Even when women sex workers are portrayed in more than one dimension in mainstream cinema, they are still usually reduced to cautionary tales or tools of redemption (and not always their own). Charlize Theron’s portrayal of Aileen Wuornos in Monster conveyed that prostitution will make a woman a serial killer. Anne Hathaway’s Fantine, in the film adaptation of Les Miserables, appears to spend only a single night doing sex work before dying of complications arising from prostitution. (But not before Jean Valjean can swoop in to have his moral compass righted by her plight.) Mira Sorvino’s escort and occasional porn performer Leslie in Mighty Aphrodite finds her way out of sex work into wedded bliss and motherhood. And that’s just a handful of the roles that have snagged actresses Academy Awards for playing deranged, destitute, and socially desolate sex workers. When women sex workers are permitted to love on-screen, their love is almost exclusively reserved for their male clients.

One doesn’t have to look hard to find disheartening and downright offensive portrayals of sex workers on screen, but the conspicuous absence of friends feels particularly cruel, and inaccurate too. Not only are these characters destined to die in the cautionary tales and to endure marriages to self-congratulatory men in the redemptions tales, they don’t even have anyone to miss them when they succumb to these fates. And the cinematic trope of a woman sex worker waiting for rescue from pimps by a male client is a far-fetched fantasy, even in the realm of the romantic comedy. In reality, victims of trafficking are more likely to be guided out of the industry safely by fellow sex workers with whom they come in contact than by law enforcement, NGOs, or any benevolent clients. Friendships in an informal and criminalized economy are not just about companionship but about surviving without protections from the legal and social institutions that are actively hostile to sex workers.

In legal sex work environments like strip clubs and dungeons, the shared goal of making money can naturally manifest in competition but that’s hardly the whole story. More often, this shared motivation results in information sharing about clientele, cursing the gods together for slow nights and poor tippers, and the same kind of water cooler gossip bonding that happens in office jobs (only the jokes about managers are usually funnier). I have spent all the money I earned working in strip clubs and an assortment of adult-oriented parties over the years and I have forgotten 99 percent of the misguided men who promised to “take me away from all this” as if snatching away my job and my friends was some great prize. But I have maintained and treasured the friendships that kept me whole in an industry society deems fit only for the profoundly broken.

*

“The thing about showing sex workers with no friends at all—it's again a kind of warning that you will pay a social price for this lifestyle,” says Juliana, a filmmaker who used to work in the sex industry. “A prostitute not only represents a ready supply of sex but also a ready supply of love to men.” Countless films feature this lonely, lovelorn hooker character but few portray the profoundly broken stereotype as egregiously as Leaving Las Vegas. Watching Leaving Las Vegas, given the size and scope of the sex industry in the city, makes it a two-hour exercise in suspended disbelief. Las Vegas is thick with tedious travelers who come in pursuit of transactional sex. Based on a novel of the same name by John O’Brien, the film follows one traveller in particular: Ben, an alcoholic screenwriter determined to drink himself to death in Sin City. Here, he meets Sera, a beautiful and seemingly rational sex worker who inexplicably falls desperately in love with him. She explores this love in one-sided conversations with a therapist who never appears on-screen, leaving audiences to guess their gender. With the exception of a few caustic interactions with a busybody landlady and a motel manager, Sera has no substantive interactions with other women. At the start of the film, she is beholden to and frightened of her Latvian pimp, Yuri, who is conveniently murdered at some point. It seems impossible that this capable woman who has the wherewithal and resources to practice enough self-care to seek therapy has not made a single friend. The presence of a friend in Sera’s life would have added a purpose besides the care and comfort of pathetic men.

A woman with no friends is a woman with a surplus of personalized attention to lavish exclusively on men. Enter Ben. When Sera meets him, she becomes singularly fixated on him, despite the fact that he has few positive characteristics to speak of, and admits as much. His most sympathetic moments in the film are when he is warning Sera against getting too involved with him. Roger Ebert, in his review of the film, wrote: “We see how she needed Ben because she desperately needed to do something good for somebody.” The assumption that Sera needed to do something good suggests that the entirety of her life is depraved on account of her profession. In the review, Ebert calls Ben Sera’s “redemption.” But why was the only option for this self-aware, beautiful woman to find redemption in a character so devoid of redeeming qualities? “In Leaving Las Vegas, the prostitute represents this unconditional love, almost like a mother for a child. So a man can think, ‘No matter how low I get there's a woman out there who will love me because she is so desperate and lonely and unlovable herself,’” says Juliana.

*

It is far less common for sex workers to fall for their clients than the other way around, but when it does happen, sex workers are treated as disposable in ways that only fellow workers can truly understand. Akynos is an artist who self-identifies with the term “whore,” is 38 and has been doing various forms of sex work for over a decade. When a client with whom she connected romantically suddenly and callously cut off ties, fellow sex workers were her most reliable source of empathy and care. “I was incredibly suicidal in the aftermath, it was other sex workers who literally helped me to maintain my sanity in that. It was their shoulders that I cried on week after week. Their expertise and trust. I don't know how I would still be here now if it weren't for them.” Sex workers don’t need a knight in shining armour to swoop down to their level and drag them up to a moral high ground, they need fellow sex workers to listen and guide them as equals: not as saviours but as true allies. “To have these [relationships] portrayed on screen is important. The audience needs to know that we are not completely alone and we can and do have sustainable healthy relationships with other people.”

Perhaps the most iconic film that falls into the client-as-saviour trap is Pretty Woman, but a silver lining that renders it more bearable is in the limited screen time devoted to the friendship between the impossibly charming Vivian and her plucky and decidedly more fun friend Kit. We first meet the pair on Hollywood Boulevard. Kit is pondering the merits of connecting with a pimp which Vivian quickly reminds her will end poorly. “He’ll run our lives and take our money,” she says. Kit recants and they repeat their work motto, “We say when, we say who, we say how much.” Their mutual support of each other allows them to remain independent and control their own livelihoods, and they’re both unselfish in doing so. This is one of the most critical aspects of the portrayal: not that they keep each other company but that they help one another navigate the underground economy in which they conduct their business.

Sex workers don’t need a knight in shining armour to swoop down to their level and drag them up to a moral high ground, they need fellow sex workers to listen and guide them as equals: not as saviours but as true allies.

Kit’s character exists largely to show how pulled together and sweet Vivian in, but anyone who has worked in the sex industry knows that Kit is the one with enough principles to go to bat for her friends. It is difficult to watch the scenes between Vivian and Kit and not long for a buddy comedy about their exploits instead of the schlocky romantic comedy that Pretty Woman actually was.

Though it was always Kit who offered Vivian truly useful and life-saving advice, it is Edward, with his money and insistence on taking her away from sex work, that redeems her. The closing scenes even vaguely imply that Kit is on her way out of the work, too. That cinematic narratives demand that sex workers stop the work if they want any hope for true redemption or love is yet another reason that portraying friendships is so vital. Sex worker friends love each other without caveats or exit strategies. But that kind of love is dangerous to social, and mostly male, fantasies about sex workers. “Because almost always these films are made by men there's something really appealing about this isolated, vulnerable woman to a male viewer or film maker—she's low fruit, she can be rescued, she is eternally grateful for the smallest kindness, she can be saved by the love of a good man,” says Juliana. In the case of Pretty Woman, even a good man is capable of defending himself by declaring “I never treated you like a prostitute” and the always condescending, “You’re so much more.”

*

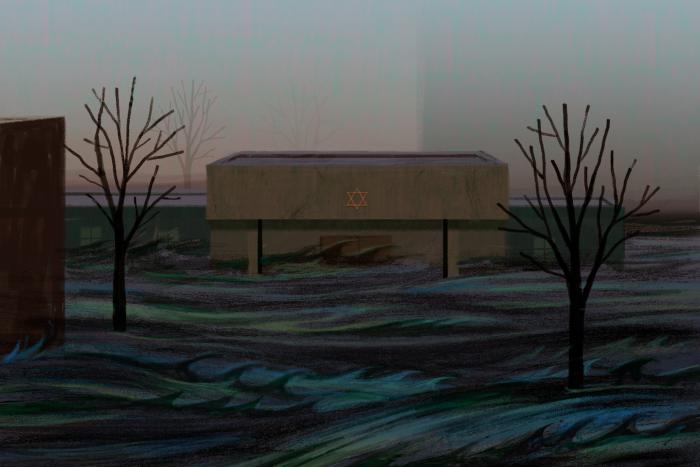

“The audience needs to know that we are not completely alone an we can and do have sustainable healthy relationships with other people,” says Akynos. “It trains the audience in a way to see sex workers as regular human beings with friendships and other bonds like anyone else living in this world.” Standing in stark contrast to cinema’s typical insistence that sex working women are without friendships for their own sakes is the 2015 independent comedy, Tangerine. The film follows friends Sin-Dee and Alexandra around Los Angeles on the day that the former is released from jail and the two set out in search of her pimp, Chester, in a series of misadventures befitting a classic buddy comedy. That Sin-Dee and Alexandra are trans, black sex workers is not completely immaterial in the film but it is hardly the focus. These women are not plot devices or cautionary tales for external gazes, their lived realities are depicted for their own sake. There are no scenes of sexual degradation and in the few scenes that do depict despair, the other friend is always close by. Whereas portrayals of a sex worker suffering and without friends humiliate her further by making her only witness the audience, the presence of empathetic friends to sex workers on screen functions to ease pain by bearing witness to it and in so doing, bearing some of it herself.

Tangerine director Sean Baker tells me that the film took the friendship-focused shape it did after he observed that friendships between sex workers in the community the film is based on were absolutely central to their lives. “The length to which they were willing to go for each other was the most profound and poignant aspect of the subject matter I was exploring,” says Baker of the bonds between sex working women with whom he collaborated on the film. “I don’t have those kinds of relationships. No one else I know does.” This reality was far more compelling than the work of sex work, and showing it made these characters far more complex than the scandalous job they do. By focusing on events surrounding interpersonal relationships instead of the work, there was an opportunity to show how the interior lives of these women are informed by the work but by no means defined by it. “We’ve seen the mechanics of the trade so many times. We all know what it is. So why harp on it even more?” says Baker. “I guess it’s still considered ‘sexy’, or at least some people think it is still sexy to audiences. I don’t think it is. I think audiences are interested in seeing the human side of this.”

*

In his review of My Own Private Idaho, Roger Ebert noted that it had “no contrived test for the heroes to pass; this is a movie about two particular young men, and how they pass their lives.” We need more on-screen portrayals of women in sex work simply trying to live their lives, with no moral compasses to realign or redemptive lights to reach at the end.

In My Own Private Idaho, the two friends sit together in the dark discussing their work and boundaries, Mike more clearly desperate for love and care than Scott. “I love you though... You know that...I do love you,” Mike sputters to Scott. And though Scott does not reply with an expression of love in kind, he lets Mike’s pain occupy the space without judgment. Scott is not there to rescue his friend from loneliness but to bear witness to it, proving by his very presence that Mike’s interior life is worthy of an audience. If only Kit and Sera had been so lucky.