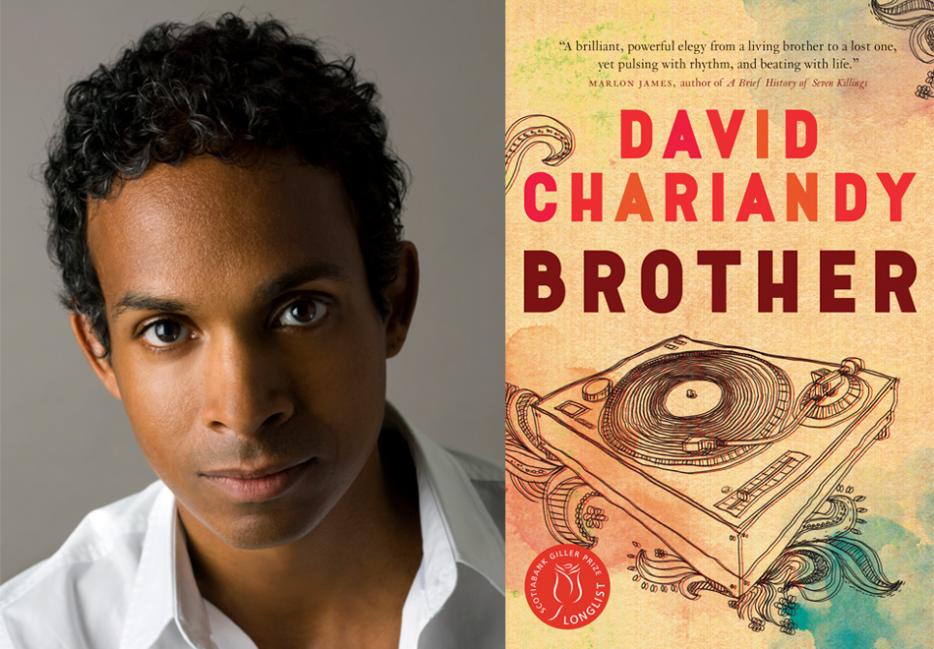

In Canada, blackness is often viewed in the shadow of our neighbours down south. David Chariandy took it upon himself to share a realistic portrait of what it means to be black in Canada with his debut novel Soucouyant: A Novel of Forgetting (Arsenal Pulp Press). This year, he managed to explore blackness on an even deeper level with his latest work, Brother (McClelland & Stewart).

Moving between Scarborough in the present day and the 1990s, Brother tells the story of second-generation Trinidadian brothers, Michael and Francis. Both are doting sons to their hard-working single mother, but as the young black men navigate adolescence, we see their paths diverge. The older and more charismatic Francis is drawn to a future in music, while the reluctant Michael finds himself less interested in following in the footsteps of his brother and the other neighbourhood boys. After a fatal neighbourhood shooting, their lives spiral into chaos and tragedy.

Brother is a slim volume, only 180 pages, but it manages to shed light on a Canada most rarely encounter. While focusing on a grieving family and community, we get a realistic view of the modern Canadian immigrant experience, with Chariandy poetically weaving in the functions of community and how intergenerational trauma shapes the way first- and second-generation Canadians view what it means to be Canadian.

*

Sarah Hagi: It’s been ten years since your last book was published. What was it like coming up with this story and the world you created?

David Chariandy: I thought after writing my first novel that a second novel would be easier. It turned out it wasn’t easier—it was every bit as difficult. In [Soucouyant], there was a relationship with two brothers that was important to me but that I didn’t pursue adequately. I knew after finishing [it] that I wanted to pursue that relationship and to think a little bit more about questions of masculinity and the different faces that black men put forward to the world. Also, when men can be truthfully vulnerable with each other about how they feel. So, that was the beginning of Brother. Then it became a kind of meditation on the gaze upon men of colour, young black men in particular, and the forms of violence that they feel growing up. The long legacies of poverty and forms of representation and prejudice that keep recycling.

Kind of like an inherited trauma?

Yes, that’s exactly it. I think that’s a perfect way of describing it. That’s probably the thing that I’ve wrestled with all throughout my writing career, the inherited trauma.

The story felt really familiar to me, as the child of immigrants. How much of this is based on your own life?

My mother came as a domestic worker in 1963. So, she lived in a Toronto that is very different from the Toronto that exists now. After years, she was able to sponsor my father. That’s a story that needs to be told—at the end of Brother, I try to gesture towards the stories that need to be heard. Maybe stories that have been told, but people need to hear them. But this is a story of immigration and a yearning for a better life.

Often, the discourse around race and blackness is American-centric. Was it important for you to show this really Canadian story about blackness?

For me that's very important, just as it is important to acknowledge that there’s a two-hundred-year legacy of black writing in Canada. And there's something very specific about how people become black in Canada. It is that process for many groups—of understanding oneself in different terms, and then arriving in Canada and realizing, I am black.

I think about that often—it’s not like my parents, who grew up in Somalia, spent their lives back home thinking about blackness.

Exactly. I imagine it’s a profound realization and it's so important for us to acknowledge the specificity of that experience, and also the diversity of it—there's many ways of being black in Canada, of course. At the same time, it’s a different landscape. Someone I really respect highly, Christina Sharpe, talks of different weather systems of blackness and anti-blackness throughout the world and what’s possible in different weather systems.

But at the same time, I think what is also really important in this novel is that in order for the young men to think beyond the narrative of themselves that they're fed, they then reach beyond Canada in music and culture, and through these cultural references they piece together a bigger sense of what it is to be black and human.

A big part of this story has to do with these young men trying to make sense of their situation and where they fit into society. One thing I found really interesting was how you fit in the struggles of belonging as a first- or second-generation Canadian in the novel. Could you expand on that?

It’s so close to my heart. And maybe that's one of the things that makes this a Canadian book in certain ways: that idea of a second-generation experience of being racialized and black in Canada, of having parents that come with certain ambitions and illusions about what Canada is. For us to grow up in this context and to know something very deeply about this country, that to me is a perspective that I think is very important—many of our great black Canadian authors write about this perspective, but also have the experience of the immigration issue.

You also see this with the character of the mother in the novel. It’s almost like she has a different understanding of how things work in Canada. She’s cooperative with the cops, for example, she wants to smooth things over. Her sons aren’t as trustful. Do you think there’s a generational difference to how we approach these things?

I think possibly. I mean, I can only speak to how I imagined these particular characters. But there was definitely a difference between how the mother conducted herself with figures of authority—how she imagined that, ultimately, figures of authority would be fair—and how the boys have different assumptions based on different experiences, [that] you can't assume that a figure of authority will be fair. So out of those two different assumptions and with two different ways of living life, there is the conflict at times between two generations.

There is also authentic love between the generations, and it goes both ways. There are times when the two generations don’t see eye to eye and it’s because they understand Canada differently. We have a very intimate understanding of Canada based on who we are and I imagine our parents have something different based on their hopes and gratitude and all of these sorts of things.

This story also explores grief and loss in a unique and subtle way. Both the mother and Michael are constantly navigating grief in the present by not really talking about it.

I think that's another crucial thing and a crucial part of it: the importance after enormous loss [of] being able to speak with others and to articulate that loss. And that's, again, the kind of work that I've done and that I hope the novel would perform—which is, after a loss, how does a family and how does a community endure? Because our communities have endured. That's the beautiful thing about people of our background. We have endured so, so much and we have come through it and that shouldn't become some sort of fairytale story of happiness.

What it should be is a reckoning with the hardships of the past and the present. But at the same time pointing out the enormous degrees of courage and bravery and great love that has sustained us as different peoples throughout history.

Also, a lot of the grief and mourning attached to the mother and even her son carries a great deal of shame, because you know how people in the neighbourhood see her. There’s a community dynamic with Francis becoming a cautionary tale.

I think that that is a part of the experience that the boys go through. A mother goes through loss and somehow perversely they're made to feel ashamed for things that they have unfairly experienced. And that’s the old story, I think, of marginalization, to perversely feel ashamed of something that was never your fault.

For people who come to Canada, there’s a way to view success in an unattainable model minority way that sometimes we as people of colour fall into believing as well. Were you trying to humanize the “unsuccessful immigrant” with your characters?

The tour of this book has just started and I’m already getting questions where well-meaning people are asking me, “Why couldn’t you tell a story that’s more optimistic? Why didn’t Michael become a doctor?” But that’s not fair to another experience, and yes, there will always be exceptions who claw themselves out of difficult circumstances and become the example. I’m not knocking those who have to play the role of the example, but I’m not really interested in that. I think sometimes an audience is looking for a story that makes Canada feel good. I’m more interested in the stories of past and ongoing vulnerability, because those are the most important stories to tell about the nations we live within. That’s the character of our nation, not the few who managed to achieve success.