Some afternoons after work, before getting on the train back from Manhattan to northern New Jersey, my dad would stop by Around The World on West 37th Street to pick up a copy of MOJO Magazine—one of the UK’s renowned music publications—to flip through on the ride home and then toss into the dusty magazine basket in our living room the next day. Towards the end of my elementary school years, I would peruse the copies regularly for the band pics, the album artwork in adverts and reviews, the strikingly imagistic band names: one group was called Neutral Milk Hotel, one was Sun Kil Moon, another was The Flaming Lips. I was building a foundation of familiarity with the music I’d end up listening to assiduously some years later.

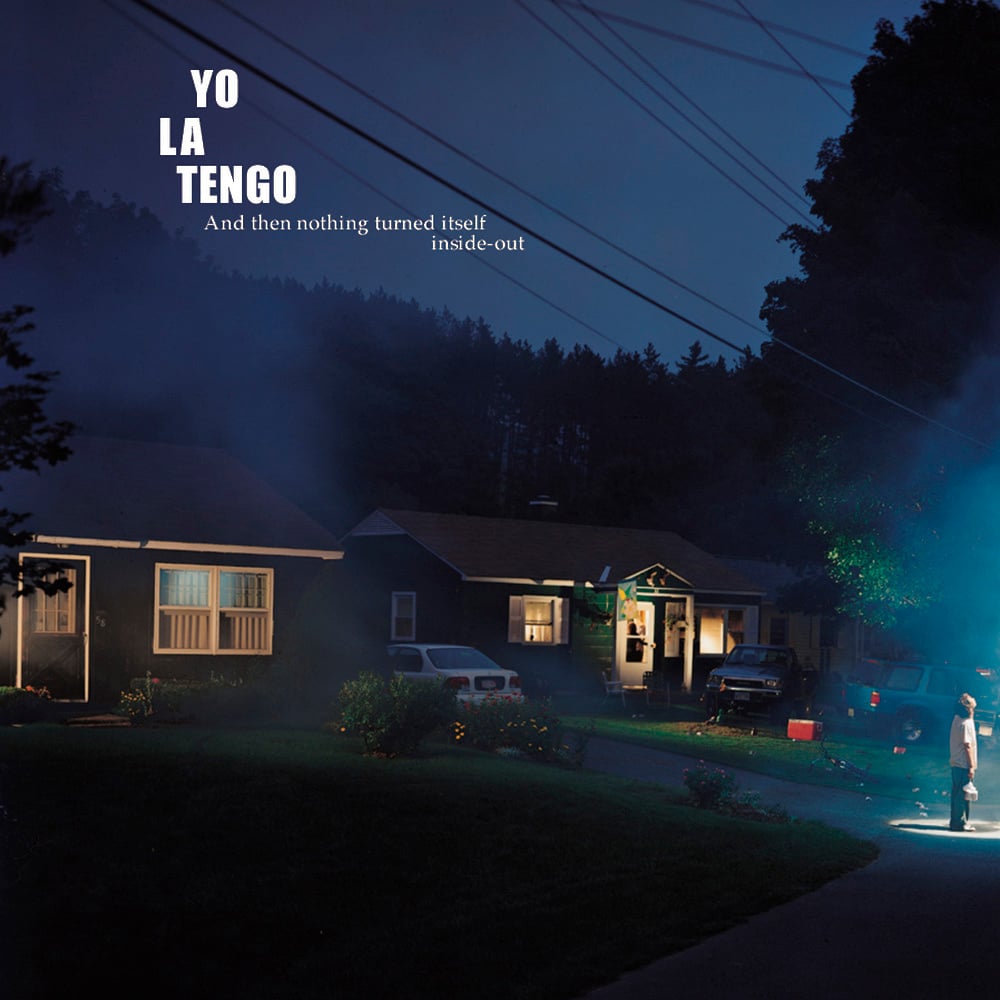

Around that time, we were heading over to my aunt’s house in the next town over. I brought along a copy of MOJO to read in the car, flipping through the pages quickly when I came across a half-page advertisement for some albums from Matador Records. There before me was an image of Yo La Tengo’s And Then Nothing Turned Itself Inside-Out. The cover artwork, Gregory Crewdson’s photograph “Untitled (Beer Dream),” perplexed me. This was my first real reckoning with ambiguity in visual text.

“Untitled (Beer Dream)” shows a man standing on the threshold of pavement between the driveway and the curb, gazing at a beam of light cast down from the top right corner. It’s one of Crewdson’s most recognizable pictures, part of his Twilight series. Published in photobook form in 2002, the series took him and a team of dozens (technicians, makeup & wardrobe, along with actors and actresses) from the arts circles of Brooklyn and Manhattan to the quiet of smalltown America, where they toiled for weeks, shooting only in the span of five minutes or so at nightfall called the “witching hour”: “The wind dies down and everything becomes still,” Crewdson said in a 2006 interview. While Yo La Tengo’s (former) hometown of Hoboken and Crewdson’s middle-America are many miles apart, the topographical disparity between the artists is bridged together by the night.

I thought the guy in the picture, dangling a six-pack in the light of the streetlamp, was getting abducted by aliens; people to whom I’ve shown the image have thought that as well. Simply because Crewdson altered the balance of lightness and darkness—a process that required painstaking accuracy to look this simple—it was reasonable to speculate on the presence in this photograph of some grand, intraterrestrial phenomenon.

But “Beer Dream” isn’t supposed to show that aliens are responsible for the preternatural occurrences in Crewdson’s middle-America. Rather, I think a word from its title summates the essence of Twilight: that these pictures depict dreamlike happenings with no precise causes. Crewdson alters the constituents manifest in a mundane location to show how waking life and somnolence are actually a single blur, how imagination lingers just beneath daily conventions; there’s no objectivity/subjectivity binary in dreams and, hence, in waking life either.

The two artists collaborated again last year, when the band’s eighteen-minute-long epic “Nights Fall On Hoboken,” from And Then Nothing, was remixed to soundtrack a live slideshow of selections from the photographer’s most recent series, Cathedral of the Pines. “My photographs are about the moment of transition between before and after,” Crewdson said in that same 2006 interview. The images that span the 100-plus pages of Twilight are a combination of indoor and outdoor shots; people in their homes or out along the barren streets. They tend to be stiff, either standing idle or sedentary, and their visages are solemn, or indecipherable. Crewdson’s lighting is meticulously patterned and distributed. When employed, it strikes through just a portion of the picture rather than completely brightening over the darkness of night, acting like a stage light borne by the natural world.

As grounded, literally, as “Beer Dream” and the rest of Twilight are in a seemingly real world, Crewdson’s art simultaneously exists on an alternate plane wrought with self-contradictions. Upon first glance, “Beer Dream” is precisely detailed in its layout, yet it looks intensely ambiguous a second later. Depicted is the banality of real life, yet an unrealness lurks beneath, which compromises its entire nature.

The music on that 2002 collaboration between the two artists, And Then Nothing, integrates “conscious” aspects into an “unconscious” setting: musical approaches Yo La Tengo had familiarized themselves with previously and been known for, incorporated into an album that marked their foray into ambient sounding territory. It seems as if Crewdson does the reverse of Yo La Tengo, integrating unconscious into the conscious—yet the approaches are symbiotic. Both artists represent and depict the same kind of imaginary, in which banality scintillates preternatural.

*

I think where my aunt lives would be a great place for Crewdson to come and plot a series one day. It’s a gated community of fully painted white, three-story homes, bunched together in groups of two or three; trees line the roads, forest engulfs the perimeter; it’s always quiet. My aunt’s place is on the periphery, right by another set of gates that leads to another community of homes. Since I was kid, I’ve wondered what it looks like over there, if the path goes on forever to gate-after-gate leading to community-after-community. But my parents have never allowed me to pursue this path; it would've been trespassing, they’ve said. For all I know, my yearning unresolved, that’s where the preternatural has been burgeoning for years.

A Crewdsonian pastiche comes to mind. The front lawn of my aunt’s home, the known, gets cast in darkness, save the muffled room-light discernible through the windows. But an expanding orb of brightness towards which I’m gazing, akin to Beer Dream’s beam of light, bulges from the left-side of the frame—just on the cusp of that gate, conduit to the unknown. No objectivity; no subjectivity. No hint at whether this is right after a family dinner, or a dream of that precise right-after. I’m just standing outside, waiting for my parents and sister, about to get back in the car.