When did ephemera stop being ephemeral? In the last few years, Genius (née Rap Genius) has bet its future on the idea and appeal of annotating virtually anything with words, broadening beyond song lyrics to literature and making high-profile hires, including onetime New Yorker pop critic Sasha Frere-Jones. You’ve probably noticed, too, an abundance of deluxe musical reissues in recent years, where any album, whether historic (Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti) or contemporary (Arca’s Xen) might merit expanded treatment. The idea has also taken root in the literary world, where supplementary materials aren’t just limited to reissued classics: the paperback editions of books from David Foster Wallace’s posthumously released The Pale King to Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? now contain essays, interviews, and meditations on the work that didn’t appear in the original hardcover printings—something like the literary fiction equivalent of bonus tracks.

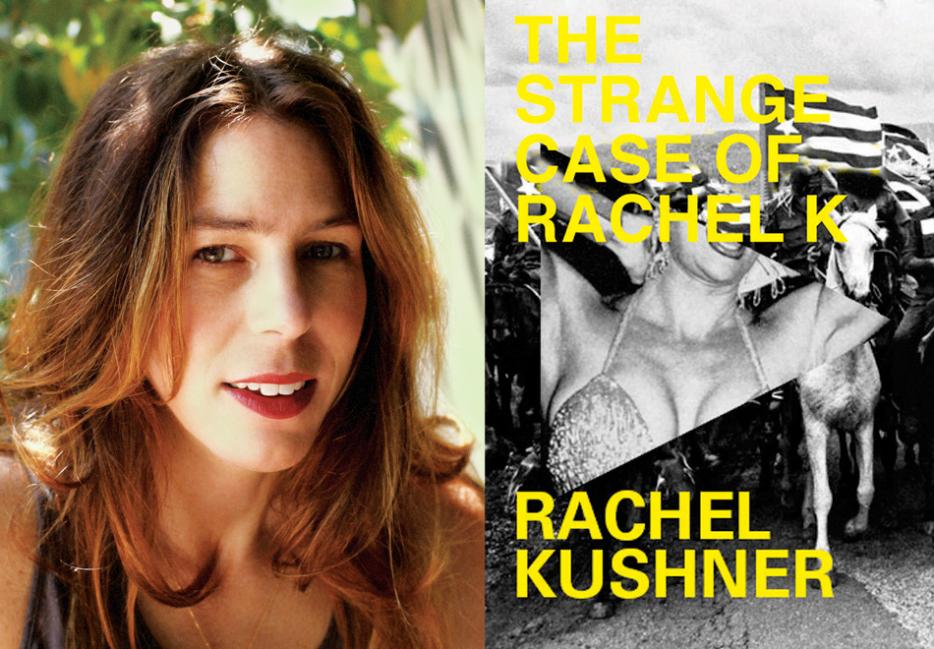

When interest in the process of making books, albums, and films is almost equal to the works themselves, stories surrounding stories can blend and overwhelm. Do we read books differently when we’re aware of the circumstances under which they’re created, even if they ultimately have little to do with the work in question? Reading Rachel Kushner’s new short story collection The Strange Case of Rachel K brings many of these issues into focus. It’s being released by New Directions, American home to numerous works by Roberto Bolaño, César Aira, and other already-prolific writers whose work’s newfound availability in translation gives the impression of an even more sustained literary output. The publisher has pushed that comparison to the forefront, noting that the three novellas collected in Kushner’s book predate both of her acclaimed novels, Telex From Cuba and The Flamethrowers. From the blurb on New Directions’ website: “these stories, like Roberto Bolaño’s Antwerp, burst forth with the genesis of her fictional universe.” In musical terms, we’re in the realm of the demos, the B-sides, the singles predating the breakthrough album.

These rarities can, of course, often rank among an artist’s most rewarding works, and musicians from TV on the Radio to the Wedding Present to Solange Knowles to the Minutemen have turned singles and EPs into vital artistic statements. R.E.M.’s cover of Pylon’s “Crazy” that opened their 1987 rarities collection Dead Letter Office raised awareness of their Athens contemporaries long before DFA reissued the latter band’s album Gyrate in 2007. More recently, TV on the Radio’s 2005 song “Dry Drunk Emperor,” an indictment of the George W. Bush administration’s handling of Hurricane Katrina, forecast the heightened political awareness that would run through their subsequent albums. And a story collection like Javier Marías’s While the Women Are Sleeping, which features stories written across four decades, both serves as a good introduction to (and overview of) Marías’s work, and proves that even a teenage Marías could outwrite many authors in their prime.11The apex of the literary/musical rarities metaphor, however, might have been Christine Smallwood’s line in her New York magazine piece on the number of Robert Bolaño books that have appeared in English translations since his 2003 death, when she dubbed him “the unofficial Tupac of publishing.” It’s a fun metaphor to mull over—and debate: For one thing, Teju Cole has convincingly argued that Bolaño more neatly lines up with the Notorious B.I.G., another musician with an extensive posthumous output. Here, too, emerges a question of perception: to an English-speaking audience, much of Bolaño’s work has been released out of sequence. The acknowledged major works—The Savage Detectives, 2666—were translated first; what’s come next has been far more esoteric. (The aforementioned Antwerp, for example, is a great deal more experimental than much of his other work, though Bolaño did once call it “the only novel that doesn’t embarrass me.”)

The Strange Case of Rachel K contains three short works: the title story, which occupies roughly half of the book, and the shorter “Debouchment” and “The Great Exception.” In a brief opening essay, Kushner briefly discusses each of these stories, sometimes speaking generally, but also specifically addressing her inspiration or process for each. The title story, which first appeared in BOMB’s Spring 2006 issue, takes its name from a 1973 Cuban film with its roots in a historical murder. The victim of that crime, the Rachel K of the title, takes on a distinctive identity in Kushner’s retelling. In her introduction, she writes:

I followed an instinct to build my own interpretation of her, making the record less vague, more specific, and procuring for her, as foil, another real historical figure, Christian de la Mazière, whose dubious and fascinating personal history is recounted in Marcel Ophüls’s documentary The Sorrow and the Pity.

Readers of Kushner’s first novel, 2008’s Telex From Cuba, will note something of an overlap here. Both Rachel K and de la Mazière appear in that novel as well, and a handful of scenes from the novella also appear in the novel in altered form. Contextually, though, there are significant differences: in Telex From Cuba, these two characters occupy larger historical roles and are part of an ensemble. In the version that appears here, their interactions are a particularly charged, sometimes sinister give-and-take. And the juxtaposition of artistic expression on one side and the legacy of fascism on the other anticipates much of the conflict that Kushner would later explore in 2013’s The Flamethrowers. It’s a fine distillation of Kushner’s preferred themes and motifs, and makes for a neat introduction to the author’s larger body of work.

The other two stories in the collection read more like outliers. “The Great Exception” is a stylized meditation on cartography and exploration, with historical figures rendered in archetypal terms, and hundreds of years of history traversed in the space between sentences. “Debouchment” is even more stylized, abounding with short and dialogue-heavy paragraphs. “If I could have written an entire book with the same density and pauses as that one short piece, I would have,” Kushner writes in her introduction. It’s difficult to read her commentary without imagining what some alternate-universe version of Kushner might have written. Would the Rachel Kushner of Earth-2 be the inspiration for a small nexus of sentence- and structure-obsessed devotees, a la David Markson or Diane Williams?

Reading The Strange Case of Rachel K offers numerous rewards and glimpses into its author’s process, artistic evolution, and aesthetic concerns. But it’s a more cut-and-dried case than most: an author’s own perspective on their formative works. Earlier this year came the news of a forthcoming new novel from Harper Lee, which turned out to be an older work from her archives, even predating To Kill a Mockingbird, that was now being readied for publication. The immediate excitement quickly soured, once observers began questioning whether or not Lee had truly consented—or, given her health, could even consent—to its release, going so far as to spark an investigation into allegations that the process constituted elder abuse. The ensuing debate over intent and exploitation has ebbed and flowed over the last few months, but seems to hinge on a central question: when it comes to the release of contested creative works, who is it more important to satisfy—the consumers seeking the edification of having access to every scrap of available work, or the creators themselves, who may have never wanted such works to see the light of day?

There’s an inherent mystique around such pieces of art, and the processes by which they were assembled; if you have several hours, Ron Rosenbaum on Vladimir Nabokov’s posthumous output and legacy can be fascinating reading, as are critic Scott Esposito’s investigations into Wallace’s aforementioned The Pale King. Not that the struggle between the sometimes-dueling desires of an author who might want their work to stay private or unread and the readers eager to read more is anything new: we might not be reading Franz Kafka today had Max Brod followed the author’s instructions to burn his work.22Of course, these situations aren’t always so contentious. In her preface to her husband Italo Calvino's posthumous nonfiction collection Hermit in Paris, Esther Calvino convincingly made the case for the book's existence, arguing that it would "effect a closer relationship between the author and his readers, and to deepen it by means of these writings." (And this isn’t just limited to literature: consider Elliott Smith’s 2004 From a Basement on a Hill, completed and released after his death a year earlier.) But that tension can place readers in a complex position: Often when reading novels, we have the luxury to engage with works in a vacuum of our own devising, to separate their genesis from the final products, and if any real-life experiences are imprinted upon them, they’re our own. The more we learn about their creation and the minutiae of their publishing—and the more that knowledge of that process becomes an inescapable part of the overall package—the more we’re forced to reckon with each one not just as an individual work of literature, but as an object of history, where the book itself is only one small piece of the story.