Stanislas Cordova’s films make people do terrible things. One woman, while watching a test screening of Cordova’s At Night All Birds Are Black, suffered a mental breakdown so severe that Warner Brothers cancelled the film’s release. Another viewer, a man, allegedly murdered an eight-year-old girl in the same fashion the killing of a child was portrayed in another of the forbidden-cinema giant’s works. Derangement and death are just two noted effects of exposure.

And yet his cult of admirers venerates him. It’s a fan-base that conducts secret subterranean screenings of such films as Wait For Me Here—the gruesome tale of a string of murders in a rural South Carolina town—in cities around the world. His work and his legend resonate, a mix of Stanley Kubrick’s reputation for secrecy and perfectionism, Roman Polanski’s flair for sadism, and David Lynch’s penchant for psychosexual dread, as well as the more avidly lurid sensibility of Dario Argento.

Given the apparent ill effects its viewers face, perhaps it’s for the best that Cordova’s cinematic oeuvre—notoriously disturbing, possibly destructive—only exists in the pages of Marisha Pessl’s new book, Night Film. The second novel by the author of Special Topics in Calamity Physics, it charts journalist Scott McGrath’s investigation into the suicide of the reclusive director’s daughter, Ashley. But McGrath feels the filmmaker’s draw, too: He’s obsessed with Cordova himself, whose intentions he’s convinced are evil.

Pessl’s fictitious auteur transcends any of those real-life peers with whom he shares his most enigmatic qualities. His imaginary thrillers—more akin to the curiously potent movies that drive the action in such novels as David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest and Theodore Roszak’s Flicker—are imbued with a power that far exceeds that of your average multiplex seat-filler. McGrath goes so far as to call Cordova’s movies “addictive opiates” that compel him to reach “an understanding about humanity so dark, so deep down inside my own soul, I could never go back to the way I was before.”

As a novel about the arcane arts and the often dastardly business of filmmaking, Pessl’s effort enters a slim canon of movie-centric works that range from mid-century essentials such as Nathanael West’s inimitably caustic Day of the Locust and Christopher Isherwood’s Prater Violet to more recent entries such as Jess Walter’s keenly elegiac Beautiful Ruins. Yet the primary focus of Night Film is not the fast talk of shark-ish producers or temperamental stars, but, rather, the potential malevolence of Cordova and his creations—celluloid nightmares with the capacity to destroy minds. Any reader who ever loved movies knows the feeling of being overwhelmed, even if that experience may have been strongest and most easily achieved during our earliest trips into the dark of the theatre (to which subsequent ones can rarely compare, no matter how large the IMAX screen). Whether that sensation is at all pleasurable, of course, is another matter altogether. Authors like Pessl prey on our fear of losing ourselves in the screen on a more-than-temporary basis.

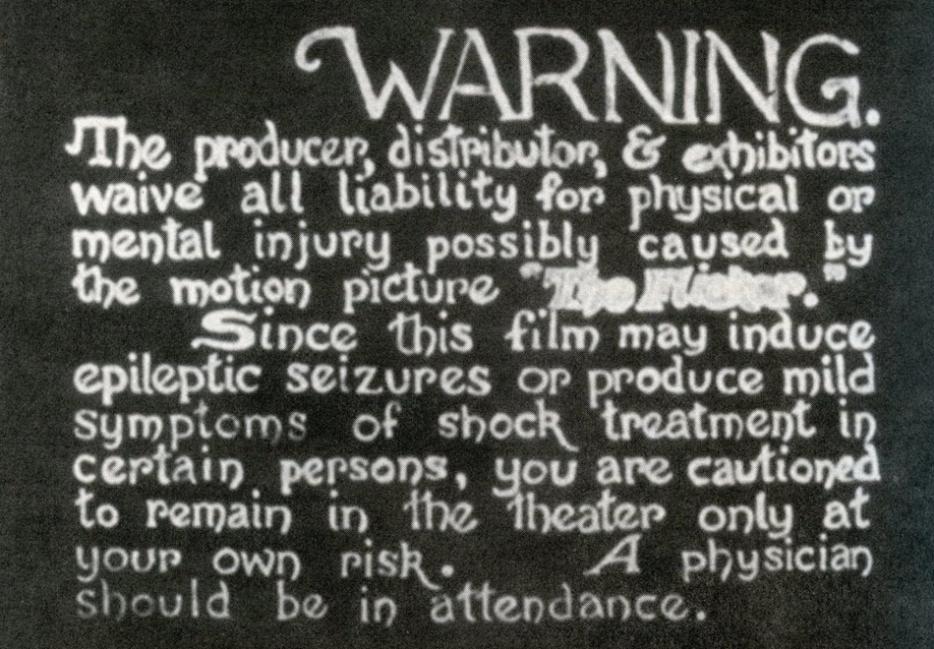

The medium’s first century was marked by many stories of movies that had undesirable physical and psychological effects. Films with rapidly alternating images of light and dark have long been known to induce seizures; as far back as 1966, Tony Conrad included a note disavowing any responsibility for “physical or mental injury” caused by his legendary eye-strainer The Flicker. Then there were the reports of vomiting and fainting provoked by the shock tactics of The Exorcist (some theatres famously handed out barf bags) and the shaky camerawork of Breaking the Waves. Movies that inspired crimes occupy another unseemly category, such as the rapes and murders linked to A Clockwork Orange or the cues that the Columbine killers took from Natural Born Killers and The Matrix.

But as disturbing as these examples may be, writers like Pessl have sought to trump them by imagining a more directly lethal variety of movie. Concocted by David Foster Wallace, the most famous of these may be the titular Infinite Jest, a movie so entertaining that those who see it lose all interest in eating, sleeping and other activities vital to their sustainment of their lives; a quest for the missing master copy drives much of the plot in Wallace’s epic novel of obsession and obfuscation. In Throat Sprockets, a beguilingly odd 1994 novel by film critic Tim Lucas, the movie referred to in the title is a similarly coveted feature that causes its viewers to develop an erotic and decidedly vampiric interest in women’s throats. Even more pervasive are the effects of the films of Max Castle, the director described in Flicker, a 1991 novel by Theodore Roszak, whose devotees include Darren Aronofsky (the Black Swan director had plans for an adaptation). A German émigré with a shadowy history in Hollywood, Castle inserted subliminal, mind-altering imagery into both his own films and more famous ones, such as Citizen Kane, as part of a Gnostic cult’s scheme to bring about the apocalypse.

If we’ve ever had that much to fear from movies, however, we’ve done a fine job of reducing their power over us in recent years. As the movie-going ritual has come to be dominated by super-sized but cozily familiar superhero and fantasy spectacles, many target readers of the likes of Pessl and the aforementioned Jess Walter appear to have given up on multiplexes altogether, preferring couch-bound forays into the more novelistic narratives of Breaking Bad, Mad Men, and other totems of quality American television. Both Night Film and Walter’s Beautiful Ruins, however, are suffused with a sense of nostalgia for an age when movies really mattered, a time before Netflix streams on iPhones gave new meaning to Norma Desmond’s line about the pictures that got small. The prematurely disgruntled production exec at the centre of Walter’s novel sums up her era of blockbuster fare as “hopped-up fantasy video games for gonad swollen boys and their bulimic dates.” Film, she laments, “is dead,” and she’s not the only mourner. In a speech this spring at the San Francisco film festival, Steven Soderbergh was unusually candid about his despairing view of the movie business he’s just left behind for the greener pastures of theatres and HBO. A few months later, no less than Steven Spielberg and George Lucas aired their gloom during an onstage interview at USC.

Given the desperate state of their beloved medium, it’s unsurprising to see why the “Cordovites” of Night Film prefer to burrow ever deeper into the master’s intoxicating tales of terror, regardless of the damage they may do to their own lives and bystanders alike. They’d rather be overwhelmed by movies that are strong enough to kill, it seems, than endure any of the more mundane forms of suffering on offer.