Suicide was the first kind of death I learned about. When I was in grade school, a classmate killed himself. Todd Webster, Julian Barnes’ protagonist in The Sense of an Ending (in which a character commits suicide), says “I have at times tried to imagine the despair which leads to suicide, attempted to conjure up the slew and slop of darkness in which only death appears as a pinprick of light: in other words, the exact opposite of the normal condition of life.”

At 21, I volunteered to work at the Distress Centre, answering calls to their hotline. Back then I still believed that there was logic to all human behaviour. You could explain everything—even the darkness. I wanted to understand suicide. There was no way to bring my classmate back. But was there a way to bring people back from the dark place “in which death appears as a pinprick of light” that Barnes writes about?

The work at the Distress Centre was harrowing; it was interesting. I signed up for night shifts, which is when the most desperate calls tend to happen. The Centre was located in an old hospital. It had a public entrance but for safety reasons (say, if a dangerous caller got overambitious and decided to visit) there was another, more discreet way to get in. You entered through the hospital’s front door and then walked through the basement for a while till you got to the stairs, which led you to more stairs, then to another hallway. At the end of it, finally, the centre: A room with a couple of couches, a shelf with books, old cookies in a wicker basket. A desk facing a window, a telephone, a binder.

The binder had profiles of some of the frequent callers. Names, sometimes descriptions, random key points: bipolar, lives on the street, has a son, calls 4-8 times a night, please limit to three minutes. There was Sam who called every hour to talk about his muscles. He also claimed to be God. There was Roger who called once shouting about Jay Leno having Chicklets for teeth. There was Katarina who was once a brilliant biologist in Russia before attacking her boss who tried to control her mind with an implanted chip. Mary whose husband hung himself and left her with a farm and three kids. There were many callers whose stories broke my heart—no one, you’d think, calls that number just for fun. Except some do. In the binder, there was also a small section called “HC” which stood for Harassing Callers. Which stood for guys who would call and try to jerk off while you were on the phone with them.

The descriptions of HCs contained identifiers that would allow the volunteer to hang up with a clear conscience before the HC would get a chance to start flogging the dolphin. Take the “Sister” guy, for example. This gentleman would begin his calls just like any other decent Distress Centre client, for example, by saying, “I am feeling really sad tonight.”

What’s making you sad?

My family.

What about your family?

Well, my sister. (And here, the first beep of internal alarm would go off.) She’s so mean to me.

How so? (This was the deciding question.)

I was home sick the other day and my sister walked out of her room nake—click.

That was me hanging up. Fucking asshole. And yet, there was, always, a moment when I thought: what if this guy was really in trouble? What if this is not an HC? What if this is a guy whose sister walks around naked tormenting him but he is not the guy whose sister is walking around tormenting him by making him lick her ass? (Some unfortunate volunteers before me got to the end of that fantasy before they figured what was up.)

Then the phone would ring again and it would be someone else and the night would move forward another minute or hour.

There’s a certain dreamy feeling to working at night talking to the Distressed. Not all of them have the spectacular minds with sights and sounds that no one else can hear. But in the middle of the night many do. As time goes on, you find yourself getting more and more entwined in the beautifully deformed reasoning of those who call. And your own sanity gives in a little. The light hurts your eyes; it is too yellow. You remember that you enter this place via the safe route. The window: who’s looking in the window, who can see you at the desk? Can anyone see you? In the hallway, on the way to the bathroom, will you run into the classmate who jumped to his death a decade ago? The periods between calls get longer. In the yellow silence, you eat all the old cookies from the wicker basket. The night is heavy on your eyelids.

Then. The phone rings.

The Distress Centre, this is Sylvia speaking.

I’m thinking of killing myself tonight.

This was the “slew and slop of darkness in which only death appears as a pinprick of light.” At the Distress Centre you always remember your first. This was mine. He could talk to me. Together, we could bring him back from darkness.

But first, you have an obligation to call 911 immediately if the caller has a weapon, a plan, if he is alone and has either of these. This guy: No weapon and no plan. There was a roommate.

Do you want to talk?

Not really. I can’t go on anymore.

Is there anything that makes you happy? (You think of questions, desperate questions to keep him on the line.)

Video games.

Video games, cool. What kind of video games?

And camping. (He was breathing fast. Hyperventilating. He must be so scared.)

I love camping too. What do you like to do when you go camping?

Have fire. I had a fight with my ex. We used to go camping together.

Tell me about it.

And then he did. I don’t remember what exactly. Something about driving with his girlfriend to the lake somewhere and setting up the tent and building a fire, and marshmallows and stars in the sky. I was sweating, relieved that I got him to talk, terrified that I had to keep him talking, what to ask, if maybe I should ask him if I should call 911 after all. But he kept on talking. He loved his girlfriend. She left him. This is why he wanted to die. Then, something about their sex life, how the girlfriend would never give him a blow job.

(Oh my God.)

He went on. He was breathing fast still. His girlfriend made fun of his penis, his girlfriend—

We were no longer talking about camping. We weren’t talking about suicide either. This was an entirely different phone call. Or was it? I remember looking out the window, looking at the parking lot, trying to see inside the cars—was he there, watching me? I turned off the light. Now I sat in the darkness, listening to my first suicide call and my skin felt clammy from sweating then cooling off too fast. Hang up. But what if he’s really going to kill himself? What if this—whatever this was—was helping him? I’ve invested so much in this call already—the paradigm of this phone call was that a guy was going to kill himself. I couldn’t just fucking shift it.

At the same time, I could no longer ignore what the breathing was, possibly, about. I squeaked something about camping and marshmallows and he said something like, yeah, yeah, camping and then breathed and then he was silent.

Tom?

I’m here.

How are you, Tom?

I’m good. I feel much better now.

But I don’t know. Either I staved off a suicide attempt or I helped a sad guy to get off. I was harassed or I was a hero because I let myself be harassed so this guy could get off and I had staved off a suicide attempt. Or he didn’t jerk off. He had asthma. He really loved camping.

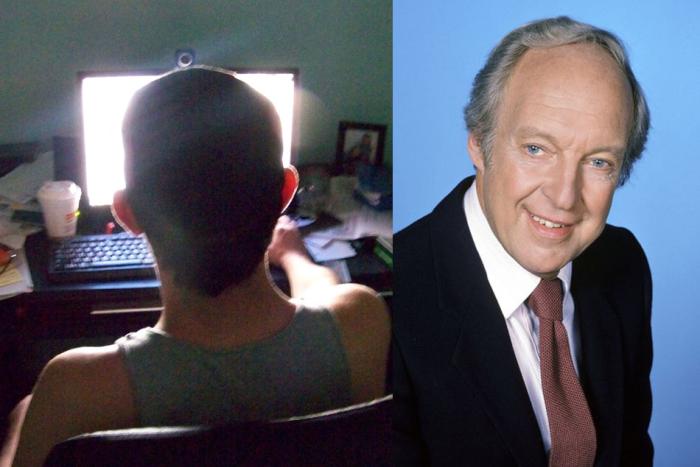

I stayed at the Distress Centre for a few more months. Sometimes I thought I could detect that voice from the middle of the night in the one HC who liked to talk about his landlady, who was also possibly the same HC who talked about his sister, who was also, possibly, the guy with the Spanish accent. I pictured a happy, sweaty guy in a stretched wife-beater, sitting on a couch in a dark basement, the TV on mute. He is cradling the phone, he is holding his penis. Or he’s a young guy in a suit, sitting in his BMW in the driveway in the middle of the night as his wife and children sleep inside their modest bungalow. Or he is a guy whose girlfriend wouldn’t go down on him, whose girlfriend left him.

I knew nothing. I had learned nothing about suicide. There was no logic. It didn’t matter. In the middle of the night, I picked up that phone for 13 months whenever it rang. That was all.