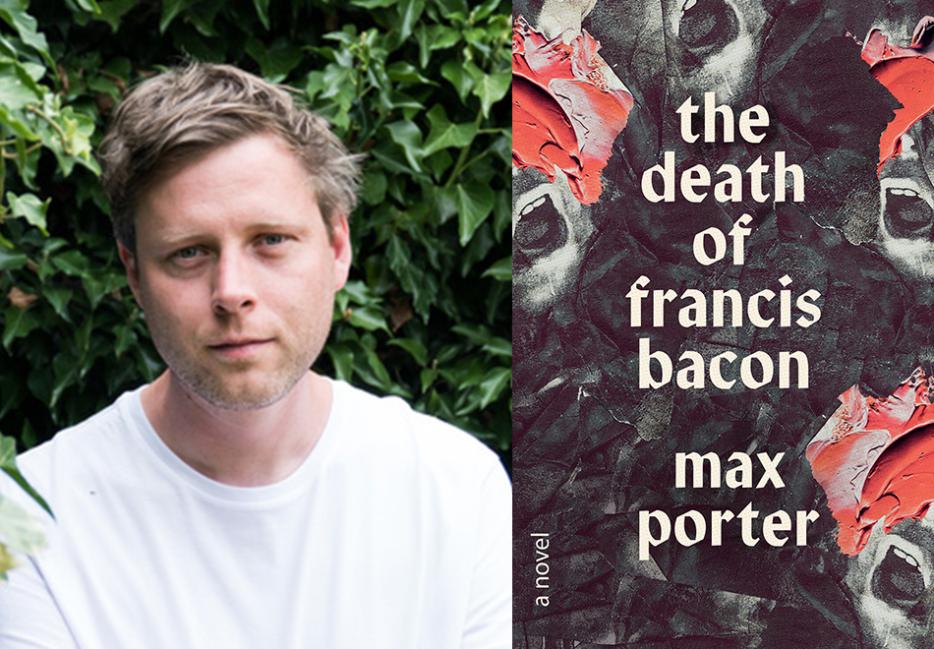

One way to describe Max Porter’s new novel, The Death of Francis Bacon (Strange Light), is wet. Wet with paint, wine, raw meat, coughs, and cum. By the author’s own admission, the novel is an experiment to be shared with the reader—something less concrete than the conventional realist novel, more open to the reader sticking their own fingers in and swirling around the dark colours and seeing what images come forth.

Set in the final days of the great Irish-born painter Francis Bacon’s death in Spain, Porter stages these hours in the narrow space between mortal terror and ecstatic joy. The tiny book is divided into seven “written pictures” (dimensions and numeric titles are given), in which Bacon and his taciturn nurse narrate an oblique shuffle off this mortal coil, portraying—to the degree that Bacon portrayed—instances of joy, pain, remorse, and visceral bodily life.

As the follow-up to his Booker-longlisted novel Lanny, and his first novel Grief Is the Thing with Feathers (which was adapted by Enda Walsh into a 2019 play starring Cillian Murphy), Porter explains that The Death of Francis Bacon is an avoidant project—a consciously made small thing, purposely uneasy with itself and the world it will be read in.

Fresh off of summer vacation, I spoke to Porter from his home office in Bath, aptly filled with vintage doll furniture and a flawless Swedish Lundby dollhouse.

Naomi Skwarna: Welcome to my kitchen. It’s where I get the best Wi-Fi.

Max Porter: Welcome to my weird little office where my son is just playing Fortnite right there. I told him he can’t talk but you might occasionally hear him being like, you know, whatever they say on Fortnite, some nasty shit.

Right off the bat, why did you write this book now and how did you begin?

My Canadian publisher Strange Light provide an answer to that in and of themselves. They’ve created this space within the corporate publishing environment for experimentation. There was a degree of, as there is on everybody, pressure, to make my “next big project,” after my last novel. I have been resisting that in almost every way. I resisted living the publicity circus to the second book, and I was always keen to collaborate with people on stage, I was keen to share the space with other writers or other disciplines. I’ve been very, very busy, collaborating with people, musicians and theatremakers and filmmakers this year, all I think in an attempt to avoid fixation on the single product, and the author as sole promoter of that product.

The whole thing started to give me heebie-jeebies, so actually I wrote this book in a very private space in a very private, intellectual mode in lockdown. I probably would have been happy to put it in a magazine or a pamphlet with a small indie press, or give it as a gift, basically, which is kind of my mentality. I mean, I’m in the gift economy! I like to think of the work like that.

The fact that it is less commercial or exists in a slightly oblique way in relation to other art historical or biographical or fictional projects, I thought that’s actually okay. I like that about it, it might be a generative thing. Also I like that there might be times in my life when I do little books, little strange books that will only interest a sliver of the people and will certainly not please even a sliver of that sliver. But I hope it’s interesting work that extends the kind of monologues we’re all having with ourselves about the meaning of fiction, the function of the novel, critical analysis, all those sorts of things.

So, that’s where it came from; addressing my own interest in Bacon’s work, and how we write about art and the failings of art history and whether fiction is a useful tool to deepen engagement with the work.

What about Francis Bacon and his work that made you want to imagine the moments before his death?

It’s a kind of engagement with myself as teenage art fan. Bacon was the first painter with whom I had a visceral shocking encounter; where I was sort of blown away by the power of the work and needed to read—and started to really understand scale. I love unpacking big canonical problematic figures, like I have this temptation to ruffle the baggage a bit, especially of someone that curated their own myth in the way that Bacon did.

You said that he was the first artist that you had a visceral reaction to. What was the context for that? Was it a particular painting of Bacon’s?

It was actually a school project. 1998. It was at the Hayward gallery. I thought it was the most extraordinary work and I came back and I chose to do it, you know, for my end-of-year project or whatever this was, I guess it was maybe my GCSE coursework or something? I tried to paint like Bacon and found I couldn’t. It coincided with my interest, in retrospect, you don’t know it when you’re 17 or 16, but looking back, it was my political awakening.

I was suddenly discovering activism and the anti-war movement; I was reading about the Holocaust and the Spanish Inquisition and British colonial atrocities. Bacon suddenly rose up out of the world of what was available to me as a student.

Bacon is very juvenile in his obsession with meat and sex and violence in a way that I felt was really compelling. It chimed with me, discovering that human beings were these killing machines, and being preoccupied with meat and the human form and the kind of artifice of figurative painting in the history of the West—thinking, Bacon is getting somewhere, pushing past that. Peeling the skin off things.

Now it’s years later, I’ve had children and thought about different modes of writing. Really, as far away from Bacon as you could get, like ‘70s minimalism and psychoanalysis and feminism and performance art, but then finding myself coming back around to Bacon. I started asking myself almost in the analytical sense: who were you as a teenage boy? What were you frightened of, what was your privilege, what was the privileged position that you were looking at art with, what was the institutional setup of your encounter with these paintings? So I suppose that’s how the setup came about, the nurse-slash-critic-slash-analyst, and the painter-slash-victim-slash-person on the deathbed. So you were asking, why did I want to kill him?

Well, yes! I know it’s a novel, but it does feel a bit like a play in terms of it being a monologue, having little directions and such. To me it felt like you were staging his death, and then he’s dead at the end, which feels very ritualistic and cathartic—

I wanted to stage it purely in the Beckettian sense of “let’s put these two people on the stage.” I have erased the idea of character completely, so in a way they’re taking turns to play the idea of Bacon. If this were a stage play, which it looks like it might be, I hope that there would never be an 80-year-old man that looks like Francis Bacon playing this part. I’m hoping it would be played by a child; by a person of color; by anybody! Anyone can take their turn at playing the part of Francis Bacon or the part of the nurse, and they might even be interchangeable. It’s a representational game, and the most boring thing would be if it were purely illustration.

It’s an effort away from the literal; to try and deepen the questions around the idea of someone like Bacon and his sense of self. I’m interested in plays and I’m interested in that directness of encounter. I’m interested in the kind of artificiality of the novel that we forget about because of the conventions of the social realist novel, where we just accept the third-person realist setup as normal, highly artificial and phony in many ways. There might be gimmicks and strategies we can employ to question artificiality; to be much more collaborative with the reader.

Speaking more about the theatrical framing of this novel—that makes a lot of sense. Can you tell me a bit more about how you see it in performance?

The starting principle for me to turn it into a play was the iconic book of interviews with Francis Bacon by David Sylvester. It’s so fascinating—he admitted in his foreword to taking thousands of hours of muddled, drunk, endless, chopped, and collapsed ranting and tidying it up into these interviews. Sometimes he had to create a question [after the fact] that Bacon would then answer. The concision and coherence of those things is a total fabrication.

I thought about translating this book, which is like a play, into a play that I hope is somewhat like a book. Really scramble the conversations and have it much more like a fragmentary or fractured state of consciousness. It’s a requiem of someone dying, and now knowing what we know of neuroscience and the way the brain works, that would involve a scrambling of everything. No longer just art, but also feeling and thought and music and politics and everything in there.

But to do this, regarding tidying up as I go from book to stage, I felt I needed to have the structural coherence of the triptych. [Holds up drawing of stage layout] So there are three blank canvases, that’s a chair, that’s a bed, that’s an umbrella, and in the stage directions the characters move in front of each canvas.

I was interested in trying to get some of the strategies of visual art into the novel, and now some of the strategies of a novel into a play. It seems to me that there’s good and interesting work to be done by my collaborators in that as well. I’m not an actor, but I hope that each of those people, whether it becomes a real thing, would enjoy that rearrangement; that drastic rehabilitation of each of these things in a new space.

Yeah, well, I mean, you seem like a very tactile writer! Even seeing your dollhouse and all the doll furniture on your windowsill—

My creepy doll furniture!

—No! Not creepy. And knowing that with your previous books, you made sketches as you were writing.

I start with drawings, yes.

Your process seems to involve some back-and-forth between one medium and another, and also now it seems like you’re moving into a live dimension with this book as well, working in time versus drawing, which is, I guess, at its endpoint, somewhat static.

What I like about Bacon is that paint was such an obsession of his and he had, like, a lifelong reckoning with the medium.

I’m not saying as the writer, I’m a visual artist or anything like that, but my reckoning is with the medium. With this book, I’m asking myself, is it possible to smear and smudge language in the way that you might smear and smudge a painted figure so you can’t tell whether it’s a figure or a carcass or shadow or a snarling dog crouching on a figure, right? Is that possible in a sentence? Painters have possibly a different leash, with regards to gimmickry. Or maybe there’s a shorter one. As a novelist, I’m not going to alienate my reader immediately so that they leave me thinking it’s nonsense.

I don’t want to suggest an indulgence on my part about the reader, but I hope that in this collaborative effort between reader and text, that might be somewhere in between poetry and prose, as you say something to do with, with space and time and texture, that is interesting to both of us. And never finished!

And maybe providing a kind of aesthetic experience, rather than a complete one?

I think that’s exactly right. I come from the oral tradition into writing. I’m not a great master of plot and the conceptual side of things. I come from the heartbeat, drum banging side of things. I want musicality, I want movement and energy in the prose that relates to sound as well as to meaning. I think fundamentally I’m that type of writer, which is why I break lines; it’s why I’m interested in hybridity. I’m sort of seeking out energy from it, more than seeking out intellectual brilliance. I feel other people are always going to do that better. Maybe this is related to a certain disillusionment on my part with the linguistic moment that we’re all in—finding things to be quite argumentative and flat and embittered.

Do you see that in fiction, or…where are you locating that flatness?

Quite evasively I’d say “oh, just in the discourse.” But what I mean is Twitter, right? I’m also a heartbroken English person, watching my country, my culture, and our relationship with the continent being severed and hijacked by a bunch of zombified criminals. Culture is going to be a victim in that war.

The Bacon book represents a kind of yell against the sterile, urbane, bitter, tetchy mode that we’re in, and speaks of Europe and painting and the transmission of ideas. It speaks of a kind of high camp, celebratory time, when we talked about art and ideas flamboyantly. I suppose a little tiny bit of me just romanticizes that generation. I suppose to stage the death of that type of conversation with that type of artist is possibly just a purely romantic gesture on my part.

You described the writing as being sort of smeared. The experience of reading it internally is—I had to sort of smear my inner vision to read it as well. It really does kind of bring you into it that way.

I wanted to write about painting, but I didn’t want to do that, like, “He puts the brush in the paint.” I needed to do it through reference to red currant jelly and pheasant, and cum and liquor and waking up in the taxi and being shocked, still in a taxi! And, you know, drugs and cigarettes and peppermint oil. I hope it’s a sort of a clarion call for us to use more than just the sophisticated, cosmopolitan, politically on-the-point language of the novel. There are other realms of experience that are relevant—and possibly even juicy.

I’m talking as if the history of Western art, which was Bacon’s preoccupation more than mine, is like a supermarket full of bodies and the supermarket’s failed attempts to describe the body. In his dying seconds, Bacon is suddenly able to describe—or feel—what the body was in relation to representation, and that should be a preoccupation of novelists, right? It shouldn’t just be cool, calm people meeting at dinner parties or in sophisticated intellectual environments on campus and having razor sharp conversations with one another about the ideas within the work. It might also include the shit, piss, cum, and the screaming and the pain—of being creative! And the constant failure to it, the constant yawning gulf of what we were trying to do and what we actually achieved, and that being directly related to masculinity as a tragic project.

It’s a vicious, violent, flawed undertaking that we are just carcasses, belching and lurching our way quite quickly to the grave. It’s a pretty tragic portrait, one that doesn’t need a thousand pages! So I hope the shortness of the book, that as you say sort of smears your mind’s eye, is somehow closer to the person—more like Bacon’s genius in paint. I hope I’ve been painterly in my novel writing.

Because of that smeared reading experience, you can’t really cling to it the way you can a more conventional text.

Yeah, and I don’t think it even needs to be for excellence’s sake. I don’t think it needs to always be a razzle dazzle affair. I think it can sometimes be a quiet escape, relating more to the inner voice. It can sometimes be a deeply held, silent conviction between you as writer and you as reader.

That’s why it’s so futile to stress out when people have bad or negative reactions to the work. Like, it’s so far beyond the writer’s control that it’s almost hilarious that people go hunting, responding to their critics or saying “you haven’t experienced it right.” What a desperately crap piece of art it would be if everyone experienced it the same way every time.

Which relates to that kind of flatness that you were talking about in so much of, like, online discourse, Twitter—

You experience it? The flatness.

I do, yeah. I think flatness is the perfect way of putting it, because there isn’t much of a way in.

It makes it seem like that’s choice. It’s tyrannical, in the way it’s made it seem like freedom but is in fact a tiny sad prism. I suppose it’s particularly like this to me because I don’t want to fight. I’m not a fighting person. I’m more of a heartbroken person, and I’m trying to reconcile my heartbroken base position—at that the scale of injustice in the world and the sadness that is out there—with my fundamentally joyful relationship with art and language.

And I suppose the Bacon book was the result—to come back to your first question and give you a sensible answer—it was a symptom of me trying to reconcile those two positions with my children here in house trying to learn, and living in this strange Zoom box, but also living in this strange miniature toy shop, and trying to map where I’m at, I suppose, in my fascination with representation and language.

It seems like Bacon, your problematic famous English man, is a good person to have fun with. We can’t let these sleeping dogs lie! We’ve got to keep poking them and see what they yield.