1. The Story

The Story is a small book, 4.75 by 7.5 inches to be exact, not much bigger than a smartphone. It’s clothbound in a maroon cover that has the rough texture I associate with libraries. When I removed my copy from a cardboard mailer branded by the film company A24 with the somewhat spoiler-y excerpt; “Florida? Murder? U have the wrong number!” my wife, a book designer, asked, “No jacket?”

She’s right, the book looks like it should have a jacket, shiny from lamination. The jacket’s adhesive should peel from age and anxious picking. It should display a cover image telling you explicitly what you’ll find inside. You shouldn’t be able to help but nervously unsheath that jacket to reveal the plain roughness of the binding underneath. There you’ll uncover details hidden by the bookmakers, like The Story’s embossed jewel-toned turquoise foil text and metallic gilded edges.

The title page of The Story informs us that it is by A’Ziah King, clarifying that #TheStory was written in 150 tweets between 9:32 p.m. and 11:57 p.m., October 27, 2015, by @ _zolarmoon. On the upper left corner of each verso page of the book, next to the page number, that handle is repeated in all caps, the online equivalent of shouting: @_ZOLARMOON.

So, King is the author of this book, and @ _zolarmoon is the author of the original tweets. King and @ _zolarmoon are the same person; the name she gave her character in #TheStory is Zola (as in “Don’t be a hoe like her Zola!!”). @zola is the name of the 2021 film that is based on #TheStory, distributed by A24 with a screenplay by Jeremy O. Harris and Janicza Bravo. The # and @ symbols are doing a lot of auteurism work here, separating the person from the persona, the protagonist from the memoirist, the medium from the message.

In the book trailer, King introduces herself as “The Real Zola.” Wearing three different looks in less than a minute, including an ombré blue wig and deadly looking gold nails, she holds up The Story, referring to it as “my new book… also known as the Thotyssey.”

The Story contains some metatext from King, an Afterword from Bravo, and an intro by cultural critic and noted Twitter user Roxane Gay. Mostly the book consists of King’s unedited, if re-contextualized, words.

The publicity materials for the book declare that this is the moment #TheStory “officially enters the literary canon.” There is a suggestion, in this project of respectability, that our new age of digital oral history can gain literary value by virtue of commercial publication.

The Story is a nonfiction book, adapting, or maybe the better word is preserving, King’s viral thread about a highly eventful few days of sex work. It’s not the first book collecting someone’s tweets: Justin Vivian Bond has one, and so does a recent American president. But this is probably the first book that translates a complete narrative arc created as user-generated content on a social media platform into a physical medium that may outlast digital screenshots. @zola is definitely the first time a story created using Twitter has been adapted into a mainstream feature film.

A24 has produced a number of promotional zines and screenplay coffee table books for their offbeat movies, which they sell on their website along with branded shirts and bags. So The Story is also technically merchandise for a movie based on tweets which are based on a true story.

The original text, @ _zolarmoon’s thread from 2015, is one of the most infamous in Twitter’s history. Zola goes on a road trip from Michigan to Florida following the promise of making exceptional money working in Tampa strip clubs. She’s along for a ride with her very new friend Jess, Jess’s boyfriend Jarrett, and their “roommate” Z. In Tampa, Jess agrees to trap (have sex for money) with clients Z sends to their hotel room. Zola refuses to personally entertain the clients, but when she sees how little Z is charging for Jess’s services, she takes over managing the operation with both sympathy and savvy. Things get pulpier from there. Jarrett is cuckolded. Jess is kidnapped. Chekhov’s handgun goes off.

All of these events are narrated with a livid incredulity by King. The criminal adventure kept the live audience of Twitter users enraptured, but King’s voice is what made her #Story a phenomenon. She displays a potent commitment to something we all share: the instinct to make ourselves the funniest, smartest, most powerful person in any life event we recount. Zola always makes the right choice, always says the thing you wish you’d said in any conflict. When Jess assures her that Z isn’t going to force her to trap: “i said ‘OH BITCH I KNOW HE NOT I WILL DEAD ASS KILL Y’ALL,’” adding, “verbatim” as if the act of reassuring you she said exactly that is all the verification we need. The minute she gets her hands on a plane ticket home, she stares down a scene in which Jarrett is begging Z to allow a sorely beat up Jess to leave the situation, too. “WELL IM READY!” she reminds them (I like to imagine her standing in the doorway with her bags, sardonically tapping an invisible wristwatch). As Jess asks if they can still be friends, Zola looks at her “like she wasn’t speaking English” and replies, “im not gon beat yo ass rn bcus u already in bad shape. But I better not ever see or hear from you again.”

As gripping as Zola’s saga was, King’s life over the past six years has had just as many twists and turns. During her “hoe trip,” Zola navigated fraud, coercion, isolation, violence, and betrayal. Since then, she’s fought to maintain authorship of her work in the mainstream film industry, which one might argue is just as full of predatory exploitation as the Florida underworld she survived (James Franco was the first to option the adaptation rights).

I spoke with King over the phone in late June 2021, the day before her movie went into wide release in the US. She sounded tired but happy. In the following days, her Instagram and Twitter would unspool a series of @zola movie premier fashion choices as maximalist as her voice—a black mesh fascinator as she signed copies of The Story on an LA rooftop, a pastel overcoat at a Fort Greene outdoor screening, hand-shaped pasties at an afterparty in Atlanta.

@zola the movie diffuses King’s authorship, not just in the screenplay adaptation by Harris and Bravo (who also directed). The film also cites as a source a Rolling Stone article called "Zola Tells All: The Real Story Behind the Greatest Stripper Saga Ever Tweeted" by David Kushner, a (white male) reporter who investigated the veracity of King’s story shortly after she posted it. All this makes her credit as the author of The Story all the more significant. As King herself told me, “In order for [stories about sex work] to mean something, it needs to be told from our perspective. Me being a Black woman who is a sex worker, my voice is purposely faded to the background. I’ve always been the been the type of person to scream louder.”

The most groundbreaking thing about #TheStory in 2015 was that it was nonfiction about sex work, told by a sex worker. There were no gatekeepers, no editors, no producers, no directors, no publishers, no publicists. No code switching, no compromises, no translations, no explanation, no concessions, no watering or dumbing down, no pandering. And people fucking loved it. They loved it for the lurid voyeurism and the subjectivity. They loved it for the salacious drama and the lyrical style. The danger and the compassion. They loved it because it was unbelievable and they loved it because it was real. Even when it wasn’t the truth.

2. The Book

The other kind of book The Story’s design is meant to emulate, of course, is the Bible. For some people, a Bible is an object associated with a certain omniscient truth. Personally, I think of a Bible more as an amusing artifact in the side drawer of a hotel room, the spot where you stash the lube. On top of a Bible: condoms, a vibrator, poppers, gloves, the things you need to grab quick. These are the kinds of Bibles you find in the backs of pews during worship, right? Not the big heavy ones that lie open at the pulpit. The kind for the response, not the call. Utility Bibles.

The word “Bible” appears in The Story, as it appeared in #TheStory and in a fourth-wall-breaking moment of the movie, too. It’s one sentence. “Bible.” In context, it means: “What I am about to tell you is the truth.” King then proceeds to describe one of the story’s most melodramatic moments, one involving attempted suicide. A moment that she admitted to Rolling Stone she made up ”for entertainment value.” So, in this case, “Bible” actually means: “Not the whole truth, but the embellishment the moment called for, wouldn’t you agree?” And we do.

King says the formal constraints of Twitter (140 characters at the time) and the excitement of live storytelling informed how she originally composed the bars. “I would type in all caps. I would need everyone to understand the emphasis on yelling. Those take up two pages in the book.” (A spread on pages 68 and 69 reads “I WAS LIKE YOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO.”) She says she had creative influence over many details of how each tweet was interpreted for its literary incarnation.

The book’s narrative flow doesn’t stick to one tweet per page. There are line breaks in the form of those ouroboros of arrows representing Retweets and the valentine heart representing Likes, along with the number of people who had performed each of these actions by the time the tweets were screenshot.

The book’s pagination stands in for the suspense between each tweet. For example, on page 80:

Bitch…

I ran so got damn fast I couldn’t even see straight.

I was OUT!!!

Fuck that (end tweet)

I run out

And

(page turn)

THE CAR IS GONE!!!

In 2015, these pauses between tweets were the equivalent of waiting seven days to find out what happens on a network television show. At the speed of the internet, a few seconds is a long time to hold your breath. The book maintains that tension.

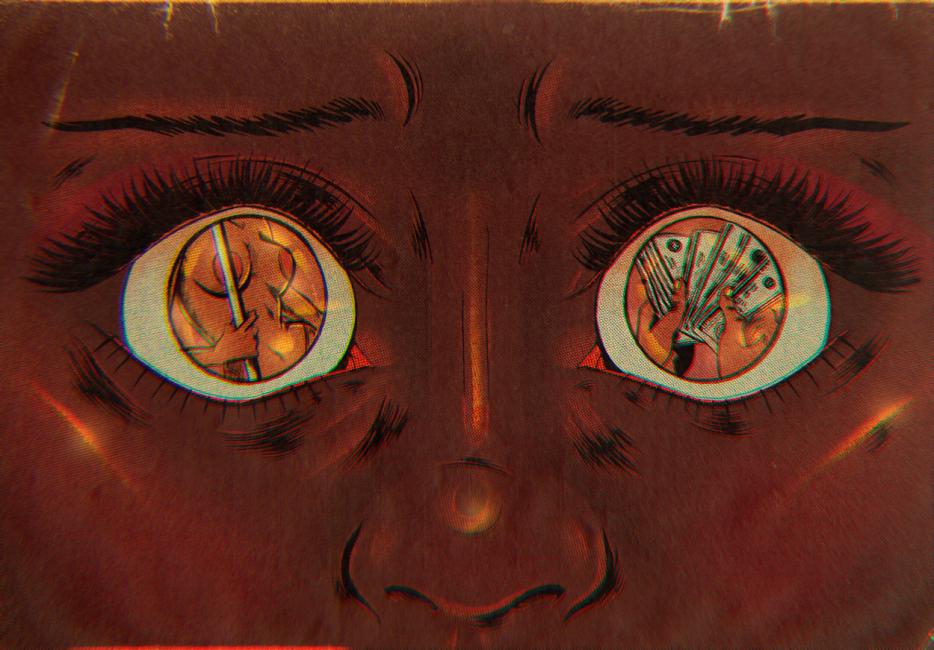

There’s a single illustration in the book, a digital portrait of the author by her friend Sarah Nicole François. In it, King is rendered as a digital avatar, intentionally Bimbo-fied, emphasizing her camp femme adornment with a glean of wet plastic shine. Her flat hair reaches all the way to the bottom of her stiletto platform heels. Glitchy fishnets wind their way up her squatting spread legs to a perfunctory bikini. Her nails are as long as pencils, her gaze both assertive and blank. The image has, in King’s words, blow-up vibes. “The way I told this story was my personality amplified,” she explains. “It was me on Level 10. My personality at its highest extent.” She wanted her author picture to have the same exaggerated effect.

In the context of the calculated classiness of the rest of the book design, King’s choice of portrait elevates The Story beyond the all-too-easy novelty of contrasting a civilized exterior with the seedy content contained within. François’s approach complicates the project of respectability, a trope with which sex workers are all too familiar. We often find that in order to tell our own stories and be our own advocates, we must demonstrate some form of redemption. That we are safe guides for you into the underworld, because we once descended into darkness but “left the life” or were “rescued.” Yet one of the links in the still active @ _zolarmoon Twitter profile is for her OnlyFans, where you can subscribe to her adult content for $25.99 per month.

By commissioning this portrait of herself, King takes control of how the world sees her; the way she wants to be seen is embellished.

3. The Tweets

Ariel Wolf, a retired stripper, is a community researcher. She is a co-author, with the collective Hacking//Hustling, of Posting Into The Void, a paper studying the impact of shadowbanning on sex workers and activists. Shadowbanning is a process of content moderation used by social media platforms in which algorithms make “high risk” posts more difficult for users to discover. The author of the offending post is given no notice that their content has been suppressed.

The way sex workers have been increasingly targeted for such platform policing “aid(s) in the disruption of movement work, the flow of capital, and further chilling speech,” the paper tells us. This is true whether sex workers are posting ads and previews related to their work or using social media for the multitude of things we all use it for; networking, organizing, education, distraction, connecting, fun, entertainment, and storytelling.

The experience of being shadowbanned differs psychologically from having an account blocked or deleted, which a user may contest and which allows them to understand the reason their online engagement has changed. It is a form of structural gaslighting, because platforms can officially deny that it’s happening. According to Hacking//Hustling; “When platforms deny something like shadowbanning and users feel the impact of it, it creates an environment in which the shadowbanned user is made to feel crazy, as their reality is being denied publicly and repetitively by the platform.”

Wolf tells me that, though it was only six years ago, the era of Zola’s original tweets, 2015, “was a very different time for sex workers sharing stories on social media.” Back then, Wolf says, she could connect with a global community of fellow strippers. “We shared tips on everything from safety, to dance moves, auditions, pictures of our cats, hustle techniques and work stories.” Social media is where she found her people.

But in 2018, the bills known as FOSTA-SESTA were signed into federal law in the United States by noted Twitter user Donald Trump. The law expands both federal and civil liability for online platforms for “knowingly facilitating sex trafficking.” This basically means that companies like Twitter that host third-party user-generated content are more legally accountable for what their users post. Framed by its Congressional authors as an aid in the fight against child exploitation, the law has increased surveillance and policing of all forms of online sexual expression, including Craigslist Missed Connections and Tumblr’s NSFW content. A June 2021 US Government Accountability Office report revealed that “criminal restitution has not been sought and civil damages have not been awarded” using FOSTA-SESTA. In other words, there is no evidence that the law has helped the people its supporters claimed it would. Meanwhile, it has had a profound effect on the landscape of online sex work.

In the wake of the new law, Wolf watched her online community disappear. “Things started to get sanitized,” she says. And it wasn’t just about having a harder time connecting with friends; although camaraderie is crucial for a stigmatized community who are treated like criminals even when they’re connecting over legalized work such as stripping or porn-making. It’s also about limited access to education and safety resources: client black lists and harm reduction information got swept up in the purge. The tech corps protect themselves from civil liability by building sexual language suppression into their functionality.

So, would #TheStory have been shadowbanned if it came out in 2021? King’s experiences demonstrate just how “messy,” in Wolf’s words, it can be to differentiate between legal labor and forced labor, entertainment and reality. Yet the thread itself contains words that Twitter’s algorithm may flag as a sign of soliciting prostitution. Wolf suspects that, today, those flagged terms “would stop it from going viral at the same speed.”

In other words, the very thing that made #TheStory a phenomenon worthy of a film and book—its pleasure rush of popularity, the sense that everyone was paying attention to it in the same shared moment—is the reason that content moderation strategies might now ensure it was seen by less people. Social media is like a casino in that way: when you get hot, systems activate to start nudging you away from your good fortune. And the house always wins.

For those who do not believe in the inherent value of adult entertainment, and do not believe the rights of those who do this work deserve protection, the limitations of online sexual expression are worth their (often misinformed) perception that children are being saved from sexual slavery.

King’s words are part of what we lose to FOSTA-SESTA, and that matters. Her point of view illustrates why anyone might make those decisions in that situation. Committing a crime is not as simple as choosing to do something illegal in pursuit of money, or thrills, or revenge.

As Wolf points out, when we lose these stories, we don’t just lose entertainment; although the importance of an entertaining story, how it generates unity and empathy, cannot be overstated. Misrepresentation of sex work leads to ideological fallacies that influence lawmakers, who then pass regulations like FOSTA-SESTA. It influences financial companies to seize the funds of those they perceive to be doing sex work. It leads platforms to shroud self-expression in insidious secrecy.

Just as The Social Network (2010) dramatized the founding of Facebook as that company’s cultural significance was changing dramatically, @zola depicts a bygone era of Twitter. The film commercializes a story originally told on a tech platform on which, because of sex censorship, it’s not possible to tell stories like this one anymore.

4. The Film

Unlike The Social Network, @zola is not about the Internet. The Internet is more like the raw material of which it’s made.

@zola is one of a slew of anticipated films finally released in theaters following fifteen some odd months where it was not advisable to sit in a windowless room with a bunch of people stuffing their faces with snacks. For many people I know, viewing @zola was their first time at the movies after being vaccinated for COVID-19.

I loved a lot about @zola. It has backstage scenes that belong in a pantheon of cinematic dressing rooms along with Magic Mike and Showgirls. I loved a shot of dehydrated piss as character development. And Bravo gets some things about sex work absolutely right. After arriving in Tampa, we see Taylour Paige (in the titular role!) on the pole, feeling herself, lost in her own zone. We’ve seen her dancing alone in her apartment, and at work she’s creating a bubble for herself where only the dancing exists, only the dancing matters. There are similar scenes in the film Hustlers, where we are introduced to Ramona’s megawatt showmanship and agility as she strips to Fiona Apple’s “Criminal,” and in the television show P-Valley, as the music drops out and we hear athletic grunts as if this is track and field, which it might as well be.

There’s an ingenious sound design trick in the @zola strip club, too. A customer leans forward and, as he bestows Zola with a single dollar, mutters that she “looks like Whoopi Goldberg.” With all due respect to the 1990 Oscar winner for Best Supporting Actress, this is not meant as a compliment. It’s a power trip, and the background noise turns on a dime to match Zola’s internal reaction: all of a sudden we’re not consumed by music, but the mundane clanks of a commercial kitchen deep fryer, the whirr of an ATM, bouncers chuckling in the lobby. It’s a profound opportunity for audience empathy with Zola’s subjective experience of this attempt at degradation. More than the novelty of texts read aloud or cell phone beeps, more than the obvious moments of terror, this moment recreates what it’s like to be Zola, a woman at work.

My least favorite part of the film, however, almost ruined the entire thing for me. It’s a scene that is not a part of #TheStory but is a part of almost every story told about sex work by people who themselves are not sex workers. In the film’s climax, attempting to get out of a difficult situation, Z uses Zola’s body as a distraction. He coaxes a threatening pimp to put his hand on her genitals before gruesomely shooting the other man in the neck.

In #TheStory, Zola’s survival instincts kick in before she even gets into that room. She’s already set herself up as a “madame,” as Z calls her. She runs as fast as she can away from Jess’s kidnappers, realizes the cops will make things worse. She stays out of sight as Z negotiates for Jess’s release. Even if the true story of what happened went down closer to the way Bravo and O’Harris shaped it, the most important thing is that King chose to characterize herself as someone sailing through the experience without this kind of violation.

When it comes to stories like this, I value the emotional coping strategies of sex workers over an agenda valued by non-sex workers. Especially when you consider the overabundance of literary classics in which prostitutes are used as metaphors for some social tragedy the author wants to explore, from Les Misérables to Les Cloches de Bale to Nana by, um, the other literary Zola.

@zola takes a lot of cues from another adaptation of a story about real life crime: Goodfellas. In both films, stylish camerawork creates a heightened understanding that we’re watching a movie, and are therefore not complicit in the violence or deception inherent in informal economies, whether it’s truck hijacking or trapping. This makes me wish Bravo had pushed beyond the aesthetics and into the thematics, the energy not just of the camera’s relationship to the story but the characters’ relationship to the politics. What Zola and Henry Hill have in common is the naturalized zeal with which they dive, at first at least, into not only crime but telling you about crime. Scorsese glorifies mob life even as he lays bare its horrors and tragedies. Hill’s lowest lows of murder and spousal abuse and strung-out chases never ever undermine how fucking cool he is. I wanted the version of @zola that begins, “As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a stripper.”

On page 55 of The Story, Zola excuses herself from Jess and Jarrett’s interpersonal drama to chill out by the pool (“I mean, i am in Florida!” is just one example of the levity she brings to heavy situations). In the New York Times’ video series “Anatomy of a Scene,” Bravo narrates the techniques she used to imagine Z visiting Zola by the poolside, an encounter that also doesn’t happen in the tweets. Echoing the kind of language used by the advocates of FOSTA-SESTA, Bravo describes Zola’s situation as “being sold into a sex slavery of sorts.”

Bravo explicitly states that she wanted to portray Z as taking control away from Zola. “A portion of the movie, you really feel like Zola is in charge of her own story,” Bravo says. “Our relationship to sex work, sex slavery, we have the privilege of experiencing at an arm’s length.” Here she makes work and slavery synonymous, while also establishing that she does not imagine her audience as sex workers, or sex trafficking survivors, themselves.

But we have Zola’s own words describing how she reacted when Z told her he wanted her to manage Jess’s clients for another night: “I was like cool. I gotchu. Especially for another $500.”

Bravo believes Z takes Zola’s voice, but King never allowed that to happen in her own telling. @zola’s dramatization chooses to taint her, but she chose not to punish herself.

King and Kushner, the Rolling Stone reporter, both have executive producer and writing credits in the film: “based on the tweets by” and “based on the article by,” respectively. Kushner, writing in the grammar of a magazine style guide, with an editorial department who answer to Wenner Media, represents the exact kind of gatekeepers, code-switchers, and defamation standards that did not stand in King’s way. In order to connect with an audience who proved the cultural impact and engagement data that made the story valuable to Hollywood, she had to circumvent all respectability. In order to verify the legitimacy of that adaptation, the film project needed to restore that respectability.

This is why The Story, the book, is such an important project. It canonizes King’s voice and what she wants to tell you about what happened. The motivation to draft and send a tweet is the same as the motivation to write and publish a book. Making sense of experience, grafting humor and ego onto the most interesting, sometimes worst moments of our lives.

5. The Canon

In @zola, the protagonist gazes at herself in the mirror as she prepares for a shift at the strip club, the job she traveled sixteen hours to do. She asks her reflection, “Who do you want to be tonight, Zola?” Her glamour becomes her agency. King the author and voice, Zola the persona and character, and @_zolarmoon the handle all understand that a calculated veneer of identity is our most valuable modern resource. On social media, and in sexuality, you may choose to control your narrative, because there is virtually no escaping someone else capitalizing on and consuming your personhood.

For this reason alone, The Story deserves its self-hype canonization as a defining narrative of the 21st century. The Story and @zola will always have the context of King telling us her version herself in the original text. She used the tool of Twitter just as Zola uses the tool of the pole. Anyone can describe social media or the strip club as inherently exploitative. For many of us, it’s not an option to remain “pure” by opting out, logging off; instead, we figure out how creatively we can maintain control. Owning our narrative does not make us invulnerable to fraud, coercion, violence, violation. But King navigated danger, survived, told her version of the story, and leveraged the resonance of that story to further struggle and further survive.

”People in the sex industry rarely get to tell their own stories, and as a result most peoples’ impressions of what sex work is like is based on the storytelling of people who have never lived it and don't view it favorably or fairly,” Wolf says. “But everyone is curious. Everyone always leans in at parties and asks a million questions if you reveal that you've done this work, for better or worse.”

On every level, King’s story is a triumphant one. Zola survived her trip to Florida, even if afterwards she explained to her boyfriend, “Neither of us r the same.” She told her story her way, experiencing not only vindication for what she’d been put through but also what we all look to social media for: as posting online goes, it must have been one of the all-time greatest dopamine rushes. She managed to leverage the popularity of her thread into a hard-won executive producer credit, and in the end she didn’t have to pander to white male celebrities in order to do it. And now we have a fascinating and well-received movie, made by Black filmmakers about Black life. And another sex work literary memoir in the canon, even if it’s at least partially embellished (as all nonfiction is).

King’s dedication in her book is eight pages long. In it, she says, “Shout out to my sex workers, my dancers, my sexually fluid beings, my straight forward but with a cherry on top communicators…”

I wanted to know what the term sex work meant to her.

King tells me, “On my 18th birthday, I went to the strip club, auditioned, and got the job the same day. From that point, it’s where I’ve felt most comfortable. When I started dancing, every day it was a new energy. I could really express myself, not just sexually, from my makeup, to my hair, outfits, and my dancing. Through that experience I really came out of my shell. I found my self, my confidence, my voice, my sense of community. In those conversations at the club, I was listened to. Not just because I had something to say, but because I had the experience.”