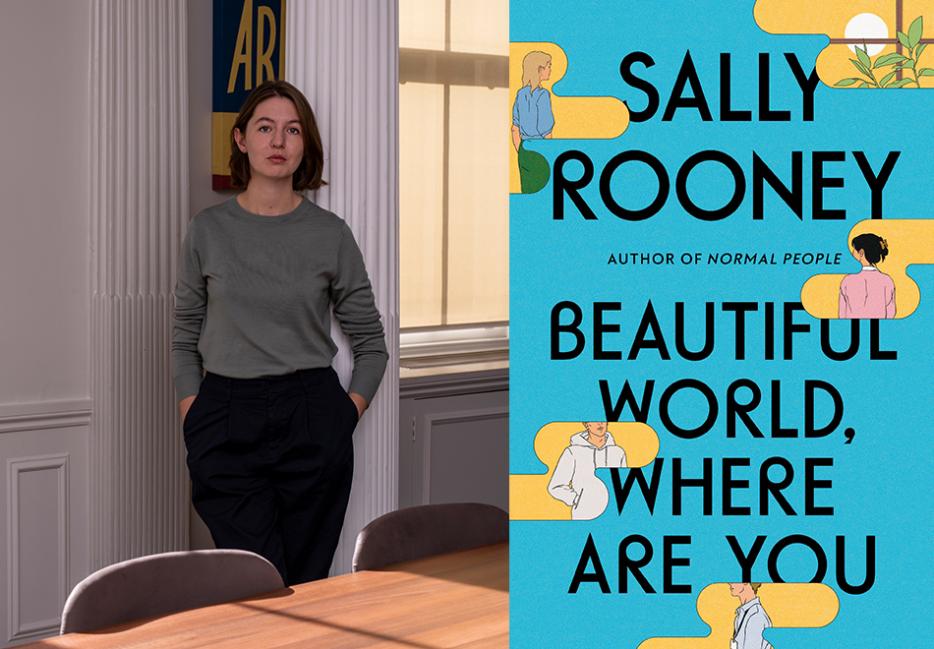

Sally Rooney’s new novel is deceptively easy to summarize: it is about four youngish Irish people and the relationships between them. Alice is a writer, Eileen is an editorial assistant at a literary magazine, Felix is a warehouse worker, and Simon works in the Irish parliament. Alice and Eileen have been best friends since university, and the novel’s narrative sections are interspersed with their emails to each other. Alice and Felix meet and start dating as the novel begins, while Eileen and Simon have known and loved each other forever. Alice and Felix live in Mayo, while Simon and Eileen live in Dublin. Like all Irish people, they spend a lot of time discussing the logistics involved in visiting each other, having many long chats about what is in reality a short and convenient car ride. They talk also about their work, their families, their feelings for each other, and about the way they understand the world. They are very funny and often perceptive, although not always about themselves.

Like Rooney’s previous novels, Beautiful World, Where Are You (Knopf Canada) is preoccupied with the problem of not being able to look inside someone else’s brain, even if you share a marked affinity or have known and loved them all your life. Her protagonists do not appear to have resigned themselves to this reality, and are constantly repositioning themselves in an effort to see each other more clearly. Unlike Conversations With Friends and Normal People, though, the narrative perspective of Beautiful World, Where Are You reflects this preoccupation. In Conversations with Friends and Normal People, we are told what Frances thinks or what Connell feels; in Beautiful World, Where Are You we are told only what the characters say and do, so that ascribing motive and intent becomes part of the reading experience. Doing this is much less hard work than it sounds—we all spend our days trying to figure out what other people are thinking and feeling, one way or another, and anyway the lucidity of Rooney’s prose means it mostly happens without noticing.

It is worth drawing attention to, though, because of what it says about the questions and convictions that drive her work as a whole. She is always interrogating what it means to live in the world with other people, what we owe each other, why we behave so oddly so much of the time, and what it means to mostly fail in our efforts to understand each other but to keep trying anyway. Beautiful World, Where Are You returns again and again to the question of perspective: where we stand in relation to each other, and where our individual little worries and heartbreaks stand in relation to a world that is getting uglier all the time. Because Rooney is so widely read, and because her novels are so frequently described as providing the definitive account of “the millennial experience,” as if there’s a common one, it has become possible to overlook how much of these conversations her work itself has driven and been responsible for, and not simply been a reflection of or reaction to. There is no one else who writes like her, and Beautiful World, Where are You is full of the observations her work is so celebrated for. It is her best book yet: radiantly intelligent, funny, sad, and evidently in love with the world, beautiful or not. I spoke to her about it over email this August.

Rosa Lyster: I wanted to start at the very beginning, because it’s my sense that all of the major preoccupations of this novel are present from the first page. Alice and Felix meet for the first time in a bar, and their interaction is described with this very striking sense of narrative objectivity: “The woman at the table tapped her fingers on a beermat, waiting. Her outward attitude had become more alert and lively since the man had entered the room. She looked outside now at the sunset as if it were of interest to her, though she hadn’t paid any attention to it before.”

How did you arrive at the decision to begin the novel from this vantage point? What does this initial sense of narrative impersonality allow you to do or say?

Sally Rooney: That decision did take some time. After I first conceived of the four principal characters and the relationships between them, I struggled for a relatively long period (maybe nine or ten months) with the question of perspective. The novel does not have one particular central character, and I wanted to find a balance between the different narrative strands of the book without imposing a hierarchy of significance. My problem was that any time I drew close enough to the protagonists to begin narrating their inner thoughts or feelings, I found myself getting bored and irritated with my own voice. Like: “great, here comes the author again, telling us exactly how everyone feels and thinks.” In my real life, obviously, there is no one to tell me how other people think and feel, and I barely even know what I think myself. So the more I tried to insist on my closeness to the characters by presenting their interiority in the narrative, the further away from them I actually felt, because their interiority did not resemble anything at all from my real experience of living.

After various failed experiments along these lines, I had to try and find another approach. In essence, I wanted to allow the novel’s characters to go about their lives without any apparent authorial judgement or commentary. And I gradually began to find that I didn’t need to present what is generally called ‘interiority’ in order to accomplish this. I could just impartially observe and describe the characters saying and doing things, without needing to speculate on what they secretly thought or felt. This decision does impose a certain distance between the reader and the novel’s protagonists, but it’s a distance that makes sense to me—basically the same distance that prevents us from reading the minds of other people in our real lives. And actually, the more time I spent writing from this perspective, the closer I felt to the characters, and the easier it was for me to observe (which is to say invent) their words and actions.

Almost all the narrative sections of the book are written in this style, or something similar (I can think of at least one exception, which we can talk about if you like!). But alongside these narrative sections, the novel also includes email correspondence between the two female protagonists. In a way, the emails were easier to write, maybe because they’re just written straightforwardly in the voices of the characters themselves. The only passages that survive from those early months of narrative experiment are in the emails. Many horrible draft chapters came and went… But some emails lived on.

Why was this important to you, to allow the novel's characters to go about their lives without authorial judgment or commentary (and I wonder if you thought of this as a moral choice first, or an aesthetic one, or both)?

It didn’t strike me at the time as a moral choice at all. I was just bored of my own judgement and commentary. And the prose felt very flat and lifeless every time I tried to write from that perspective—“he thought,” “it reminded her,” and so on. Partly it might have been because I had recently finished writing a novel in which the perspective did switch back and forth between two protagonists in the third person. And they were always thinking and feeling things, and I was always telling the reader what they thought and felt. So I had kind of exhausted that narrative technique for myself, at least temporarily. I didn’t want to write that novel over again. I had to [do] something that to me felt sufficiently different. There are a lot of things I won’t or can’t do in my work, so the number of things I will or can do is therefore necessarily constrained. And the effects of that constraint may as well be called “style.” But I don’t consider myself a talented stylist by any means. Like any writer, I have an aversion to anything that feels false or boring in my work, and the authorial commentary I was producing on these characters felt both false and boring, which eventually led me to develop the narrative technique we’re talking about.

So the decision was as purely aesthetic as possible, at the time. But now looking back at the whole process, I think there was, if not a moral aspect, maybe a “philosophical” aspect to the development of this technique. I am interested philosophically in the degree to which we can know other people, and ourselves. In life, obviously, we have to get to know people without ever having any direct insight into their internal thoughts. The novel as a form typically gives us more privileged access to the inner lives of others than we get in real life. But novels don’t by definition have to do that. And as I went along, I found that I actively wanted to write a novel in which the characters were revealed through their outward behaviours, their actions and words, rather than their inner thoughts and feelings—the way other people are revealed to us in real life. In this novel, we still have privileged access to the characters in many ways, because we can observe how they behave in intimate situations, and we can read private correspondence between them, and so on. But nothing more than that. I was interested in the question of whether, by the end of the book, we “know” these characters less well than if we had been told directly what they were thinking and feeling. My intuition is that we get to know them just as well without that—but then, I invented them, so it’s hard for me to judge.

It seems like the way you wrote this novel was to conceive of the characters first and then set about observing/inventing what they were saying and doing. What is it about these characters that made this novel possible?

Yes, I conceived of the characters first, and then I got stuck for a little while. Two of the central characters, Simon and Eileen, have known each other for almost thirty years. Two others, Eileen and Alice, have known each other for about ten or eleven years. And another two, Alice and Felix, have just met. So from the outset, I had no idea “when” the novel started. Some of the most interesting and exciting scenes seemed to have happened many years previously—when Eileen was a child, or when Alice was in university. Did the novel begin all the way back then, and skip forward to the present? Or did it begin in the present, and incorporate scenes from the past? I knew the three narrative strands were all interconnected—the story of Eileen and Alice’s friendship did somehow “involve” their respective relationships with Simon and Felix—but the interconnections were not immediately obvious.

So from the start, the idea was basically three linked relationships, spread out over the course of thirty years or so, happening in various cities and towns in Ireland and elsewhere. The task of turning this idea into a novel was challenging for me—my last two books were easier to fit into the shape of novels, I think. But the day-to-day writing process was the same. I imagined my characters in various different little scenarios, and typed out the scenarios on my laptop. While I was typing, I had the mental image of my characters before me, doing whatever it was that the scene required—walking around, eating dinner, talking on the phone, or whatever. And more often than not, nothing really interesting would happen. The character would finish having dinner, or talking on the phone, and that would be it, and the scene would end up in a “deleted work” file on my computer. But sometimes, a character would do or say something interesting or revealing, that seemed to signal some shift in their relationship with another character, and the scene would take on a new quality. This is the only way I know how to write a novel, or any kind of fiction. I have to write two or three scenes for every one that makes it into the book. But I tell myself the process is worthwhile because it teaches me about my characters and deepens my understanding of the work. (Whether that’s true or just a consolation I don’t know—it might be true!)

You ask another question here—what was it about these characters that made the novel possible? And one answer is: their relationships with one another were sufficiently interesting to me. I wanted to understand Simon’s feelings for Eileen, and her feelings for him; and Alice’s for Felix, and his for her. And I wanted to get to know the two women and their friendship, which struck me as complicated. The novel seemed to have a lot of moving parts, in terms of the dynamics between the characters, and how one dynamic affected all the others. And that made it more difficult to write, but also more enjoyable in a way—it felt closer to the inter-connectedness of life. But another answer to the question would be: I loved the characters. And when I’m writing about characters I love, I’m motivated to write about them at great length, and to continue writing even when there's seemingly no plot and nothing is working and I have no idea what I’m doing. So that was a necessary ingredient in the writing of this book, and in everything else I’ve written too.

What do you love about these characters?

The idea of loving a fictional character is something that gets discussed a little bit in the novel itself. It's an interesting idea for me, partly because all my life I've loved fictional characters very much, and in a way that has felt meaningful to me, almost like loving a real person. What does it mean to love a person who doesn't exist? And relatedly: what does it mean to love a person who does?

One thing that strikes me is that loving someone is very different from liking them. The four protagonists of this novel have an array of different attitudes toward religion—but to draw briefly on the Christian perspective, Jesus did not teach us to “like” our enemies. If we liked them, I don't think they would be our enemies. They can still be enemies if we love them, because love is more complicated and difficult—capable of extending to everyone, without losing meaning or exhausting itself.

With that in mind, I certainly can't say I love these characters because of their likeable personality traits. In the course of the novel, we have an opportunity to see them all at their worst—at their most unreasonable, cold, aggressive, bitter, selfish. Many readers will doubtless find some or all of them “unlikeable.” That's okay. I wasn't trying to create characters I approved of or looked up to—but equally I wasn't interested in writing about people I considered morally beneath me. We also have some glimpses of the protagonists at their best, and they can be very caring, very thoughtful, and so on. The reader may feel superior to the characters, but I don't. If I did, I wouldn't have written the book.

I might be crossing into moral terrain now, which is probably a bad idea. But I believe that, while not everyone is “likeable,” everyone is loveable. Part of what motivates me as a novelist is the challenge implicit in this belief. I want to depict my characters with enough complexity, and enough depth of feeling, that a reader can find a way to love them without liking them. Or even like and love them despite everything—as I do.

I love these characters too, especially Alice and Eileen. At times, their relationship seems like the most intense one in the novel, or at least the one with the most at stake. There's this description early on of how they see each other: “Alice said that Eileen was a genius and a pearl beyond price, and that even the people who really appreciated her still didn't appreciate her enough. Eileen said that Alice was an iconoclast and a true original, and that she was ahead of her time."

This is as sufficient an explanation for why they love each other so much as anyone could ask for, but I still wanted to ask you: why do they love each other so much?

I agree there's a lot at stake between them. It actually reminds me of a conversation I had with one of my own best friends when I was writing my first book—I told her I was worried that the drama was too “low-stakes,” and she replied: “What could be higher-stakes than love and friendship?” It's a great question! And for me, the answer is literally nothing. There have never been any stakes higher than love and friendship, in my life. For other people, in different circumstances, the answer might obviously be different. But for me, and generally speaking for the characters I write about, love and friendship are supremely important.

As to why Eileen and Alice love one another so much—I think there are a lot of different reasons. In some ways, they're drawn together by the things they have in common: their inability to “fit in,” their distrust of what is popular, their analytical tendencies, their senses of humour. And in other ways, they're brought closer by their differences from one another. Alice admires what she sees as Eileen's more serious intellect, her ability to be thorough and “do the reading,” and also her attractiveness—her physical beauty, her elegance, her charm. And Eileen admires what she sees as Alice's extreme self-assurance, her indifference to the opinions of others, her uncompromising personality, and her accomplishments. Each sometimes sees the other as a reflection of herself, and then at other times as an image of everything she is not.

But those are more like the reasons why they like each other. And their feelings really go far beyond that. In fact their love for one another is probably close to unconditional. That might seem to imply that nothing is really at stake between them, because they are going to love each no matter what happens—but as we see in the novel, a loving and admiring relationship can also accommodate a lot of resentment, anger, disappointment, pain, and so on. I suppose we are never really in doubt about the intensity of their feelings for each other. But we do probably doubt at times whether they can go on being friends, or at least I did.

I want to ask you about Alice, whose career and public profile resembles your own. At one point she says, “the novel works by suppressing the truth of the world ... And we can care once again, as we do in real life, whether people break up or stay together—if, and only if, we have successfully forgotten about all the things more important than that, i.e. everything. My own work, it goes without saying, is the worst culprit in this regard.” What's your own relationship to this idea?

I think the back-and-forth structure of the email exchange was really important for me in this regard. When I wrote that passage from Alice's perspective, I did strongly agree with what she was saying—I felt immersed in her life and her experiences, and I was persuaded by the critique that she had developed from those experiences. I still definitely think she has a point about the novel as a genre. But in the next email, we hear from Eileen, who offers a contrary perspective, not from the point of view of a writer, but from the point of view of a critic and reader. Writing her emails, I felt equally immersed in her personality and experiences, and I was brought around to her perspective instead. So although the protagonists were disagreeing with one another, I was able to agree with both of them—which meant the emails became something other than a compilation of my own opinions (I hope).

But I am still interested in Alice's critique of the novel as a form. In a time of gigantic historical crisis, maybe we should try to fixate less on the tiny details of our own emotional lives, and maybe our cultural forms should try to reflect that shift—away from individuals and relationships, towards the biosphere and global power structures. Intellectually, that makes sense to me. But it's very hard, as Eileen argues in her next email, to make that shift sincerely in our own personal lives. Almost nobody can really care about (e.g.) bees as much as they care about (e.g.) their own spouse. Many people do sincerely care a lot about bees, but almost everyone cares more about their spouse. And the novel is not a didactic form by nature. For the most part it reflects or tries to reflect the psychological and cultural realities that predominate in the real world. There are doubtless novels out there that manage to place bees on a par with spouses, and that is certainly a worthwhile challenge for a writer. But it's not something I could with any sincerity attempt myself.

There is also the argument that novels about relatively wealthy Westerners are the equivalent of television shows about royalty or aristocracy. These forms of story-telling present a world in which luxury is the predominant way of life for most people—the existence of poverty is acknowledged, but mostly kept off-screen. At the absolute most we get the impression that the world is divided pretty equally between rich and poor. And of course we know that in real life, the rich—even if we extend that to include the fairly ordinary Europeans who populate my novels—make up a tiny percentage of the world population. They take casual international flights, they drink takeaway coffee, they stream high-resolution TV shows on their laptops, and so on—all completely anomalous behaviours for most human beings on earth. People like Felix and Eileen are certainly not “rich” by Irish standards, but by global standards they are. This is not to blame them, or to blame myself, for the good fortune of being born in a wealthy Western nation in the 1990s—especially since Ireland is not a former colonial power, but a former (and partly current) colonial subject. But the fact is that the lives of people in Ireland today are simply not representative of the lives of most people on earth. That is a problem Alice cannot solve. I tried in this book at least to articulate that problem in some way, but whether I managed that, I don't know.

Now I want to ask you about Eileen, who also often says and does things that seem likely to lead readers to draw parallels with her creator. I’m thinking specifically about this bit: “When I first started going around talking about Marxism, people laughed at me. Now it's everyone's thing. And to all these people trying to make communism cool, I would just like to say, welcome aboard, comrades. No hard feelings.” A lot of critical discussion about your work focuses on your going around talking about Marxism, and I think this will inevitably be interpreted as your directly addressing that. Did you have any doubts about including something like this, or was it an easy decision?

If it is permissible to admit this, I personally find Eileen's petulance about Marxism in this scene quite funny. Eileen did not invent Marxist economic or social analysis, and she obviously was not the only person “going around talking about Marxism” in 2010 or whenever. In that sense, a completely ridiculous claim, and for that reason kind of funny, at least to me. But on the other hand, I'm sure she did meet people in university and elsewhere who laughed at her opinions, and who now put out tweets about “smashing capitalism” or whatever. You know, Marxist critique has gotten a lot more popular online, and for good reason. Eileen both welcomes and slightly resents this development. I guess I would say that in her case, the welcome is political, whereas the resentment is personal. Whether I share in those feelings, I couldn't possibly say.

I think all four of the protagonists of this book probably agree at least to some extent with Marxist analyses of capitalism. And so do I, and so do a lot of people I know. My parents are lifelong socialists. My mother grew up in social housing and worked in the local arts centre until she retired, and my father was a technician for the national telecoms company. So I don't come from a very wealthy background—which has probably informed my worldview just as much as my reading of Marx has. But part of the discussion Eileen is having in this scene is about what constitutes the “working class” in Western liberal democracies now. Does it include, for example, people like Felix? Almost certainly yes. People like Eileen? Maybe not. They both work for a living, and neither of them make much money, but the term “working class” is now tied up with a lot of other things, to do with education and cultural capital rather than work and income. I'm interested in that argument not only intellectually, but probably also because it touches on questions about my own identity and my own life.

I didn't mean to address my critics directly, however, because I don't really read my critics and have only the faintest idea what they are saying about me. That's not to say that their criticism isn't worth my time. I'm sure it would be worth my time if I could bear to read it, but I can't, so I don't. I remember reading one piece about Normal People—it was a review by Helen Charman, published on the White Review website. It was really quite critical of the novel in places, but I thought it was an excellent piece, full of insight. I admire Charman as a critic. But I don't have the inner tranquillity required to read criticism of my work most of the time.

Quite early on, Alice writes an email where she says: “If I had bad manners and was personally unpleasant and spoke with an irritating accent, which in my opinion is probably the case, would it have anything to do with my novels? Of course not. The work would be the same, no different. And what do the books gain by being attached to me, my face, my mannerisms, in all their demoralising specificity? Nothing. So why, why is it done this way?” Does the arranging of literary discourse entirely around the figure of the author feel to you like a new development, or do you think it's always been like this?

I don't feel qualified to comment on the literary discourse of the past. In fact, I'm not even really qualified to comment on it at present, since I almost never read author interviews or profiles of other writers (or, obviously, of myself). I'm not sure if I've ever read a straightforward biography of a novelist, or even a literary memoir. I'm a big fan of books, and there are many writers whose work I would say with complete sincerity has changed my life. But I don't generally care to know anything about their personal lives, especially if they're alive today.

I might be wrong, but I suspect this is something I have in common with most readers of novels. Generally speaking, the readers I know and meet through my work are interested in the fictional inhabitants of a novel's interior world—not in the real-life personalities of writers. So why is the figure of the novelist so prominent in media coverage of books? I don't know. Partly I think it's because there's a readymade template for arranging media coverage around a particular central personality, and that template is “celebrity.” We seem to be stuck with that. There is no real reason why anyone should want writers of literary fiction to be presented in the media as minor celebrities—with profile pieces and photo shoots and so on. But because press coverage of novels is so exclusively focused on the figure of the author, writers are required (usually by contract) to engage with the paradigm to some extent. It seems like it would be better if we could do it another way.

Why am I doing this interview, then?? I suppose I don't take the point that far. I think the conversation we're having now is about my work rather than me, even if it can be tricky at times to separate the two completely. And I do enjoy talking about my writing, if there's anyone interested to listen. I have friends who are writers, and I always enjoy talking to them about their work too. I think there's something to be said for people in any field discussing how they do whatever it is that they do. But I can't accept the idea that my personality should become an object of public discourse just because I've written a few books. I get the impression that Alice, a fictional character who has also written a few books, finds this even harder to accept than I do.

Back to your answer to the first question, and the decision to impose a certain authorial distance. You've said that almost all the narrative sections of the book are written in this style, with one notable exception. Can you talk a bit about the wedding section?

Close to the start of the book, we learn that Eileen's sister Lola is preparing to get married, so from early on I knew the novel would have to include a “wedding scene.” I thought this would present some nice dramatic opportunities, because other significant characters would be there—Simon, his parents, Eileen's parents—in combinations that might otherwise be unlikely. But when it came time to write this section, I found myself doing something different. Instead of presenting a scene or series of scenes through dialogue and dramatic action, I was trying to present a kind of sensory experience—a series of images and memories and moods. This allowed me to steal a glimpse at the inner lives of some of the novel's “minor” characters, like Lola, and Eileen's parents, who I loved. And it also allowed me to present—in a kind of loose fragmentary way—the thoughts and memories of two of the novel's principal characters, Simon and Eileen.

I've talked a little bit already about the challenge of writing about a relationship of such long duration. Simon has known Eileen since she was born (and Lola even longer). How could I condense a lifetime of changing feelings into the space of this novel, especially without the use of traditional interiority? The question seemed to present itself with renewed force at the wedding, because Lola had been so intricately entangled in the dynamic between Simon and Eileen as children. I even wondered whether their relationship might have echoes in the dynamic between Simon, Eileen, and Alice later on. But if I'd tried to present this story conventionally using dramatic scenes, it probably would have run to the length of a novel on its own. I had to find a way to compress the depth of feeling between the characters into a much smaller space, using different techniques. And Lola's wedding seemed to provide circumstances of special pressure and intensity for the characters to remember and re-experience one another in a new way.

In the months before I wrote that scene, I had also attended a couple of weddings myself, and I'd found them very moving and beautiful. I don't know if other writers feel this way, but I think it can be much easier to convey disillusionment, alienation, and ugliness in fiction than it is to convey love, happiness, and beauty. Some people might conclude from this observation that life is “really” alienating and ugly, and that love and happiness are illusory. But I don't think so. And in the wedding chapter maybe I was trying to suggest in some very small way the beauty of life.

Finally, I want to ask you about the title, and the Schiller poem it's derived from, in relation to what you've just said. To me there's this interesting balance in the novel between the suggestion that we are living through a uniquely shattering period of historical crisis and that the world is uglier than it has ever been, and the suggestion that people have always felt like this, that a beautiful world is lost or vanished. Maybe an easier way of asking this is: what made you choose a bit of a Schiller poem for a title?

I think the balance that you identify here is exactly right. In the early stages of writing the novel, I became kind of fascinated with what is called the “ubi sunt” motif in literature—meditations on decay, ruin, and the transience of beauty. In Latin poetry, in the writings of the Anglo-Saxons, in the literature of industrial-era Europe, there is this recurrent sense of a beautiful world passing away. Writing in the eighteenth century, in what is now Germany, Friedrich Schiller locates the beautiful world in Ancient Greece. But it seems to me that it can be located in almost any particular civilization as long as it is definitively gone forever.

Our present sense of a beautiful world passing away can feel quite new and unprecedented, because of our political moment and because of the climate crisis. But our cultural terminology for this experience long pre-exists our present circumstances. Obviously that isn't to compare contemporary climate anxiety to (e.g.) medieval apocalypticism. The ability of our planet to support human life is very genuinely in serious danger. What interests me is that we have to find some way to express this anxiety using (at least to some extent) our existing vocabulary and cultural forms.

In The Gods of Greece, of course, as in the “ubi sunt” tradition more generally, Schiller has already located the beautiful world in a specific place and time. I don't do that in the novel. And out of context, the title of the book might even sound vaguely hopeful and forward-looking, as if the beautiful world might be right around the next corner. It's probably not. But while the characters in this book are certainly disillusioned, maybe even embittered, they haven't entirely lost hope. And most of the time, neither have I.