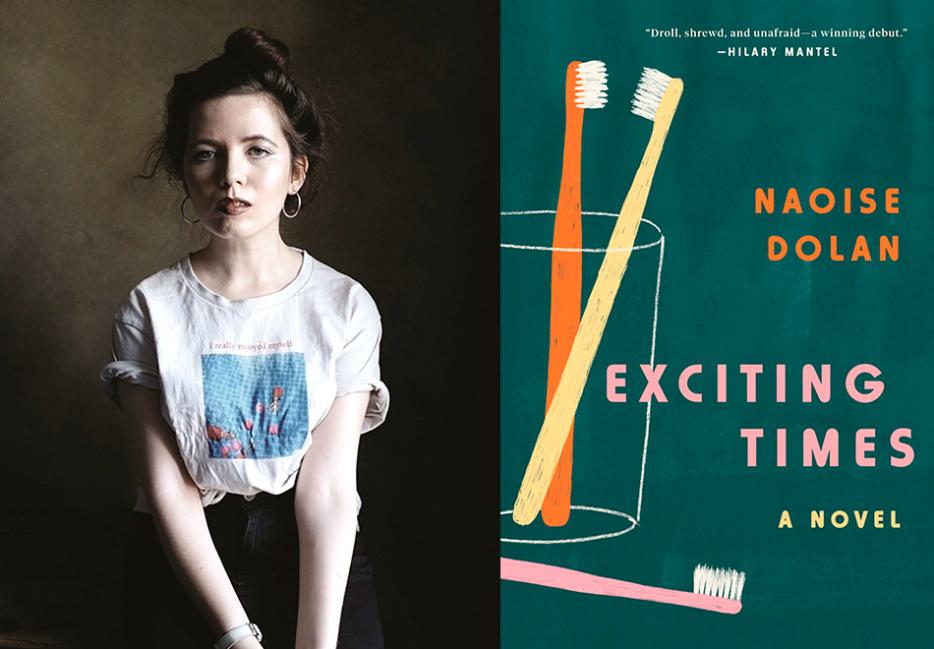

Naoise Dolan’s debut novel, Exciting Times (HarperCollins), follows twenty-two-year-old Ava as she leaves Ireland for the first time for a teaching job in Hong Kong. It’s a story about taking a not-quite gap year to see what else is out there, and how much money you can make in circumstances different to the ones you grew up in. But it’s also a story about class, gender, sexuality, language, and the danger of the space between how we see ourselves and how others see us.

This is Ava’s story, but other people’s feelings and pride are at stake, too. There’s Julian, a British banker, coolly self-aware of his privileges yet non-committal about the arrangement he seems to be in with Ava (living together, sleeping together, a “let me know if you need anything” attitude towards cash and credit cards). And Edith—a twenty-two-year-old Hong Kong local, unapologetically earnest, a lawyer with a “churchy” accent who’d studied abroad in the UK. Both form an unlikely love triangle with Ava who is hungry for connection and belonging as she figures out who she is away from home.

The novel hums with the intermingling thoughts of people wanting to be understood, avoiding, oversharing, reading and misreading each other: through drafted text messages that accidentally get sent; international phone calls; thoughts that don’t get verbalized, and things said out loud that should’ve remained a thought. It’s also a story about anticipation: how your whole life can change depending on the people you choose to have—and keep—around.

I spoke to Naoise Dolan in the lead-up to the North American release of Exciting Times, in the midst of a global pandemic.

Nathania Gilson: I remember how you’d mentioned last year that apologising wasn’t just something women did, but an inherently Irish thing, too—I was wondering if you ever thought about this as you were writing out Ava’s thoughts? There’s a bit in the novel where she says her favourite conversations are the ones where she says precisely what she thinks. I’m wondering how the character of Ava was a way of challenging what we think is difficult to change about ourselves?

Naoise Dolan: I think there’s often a flattening honesty to how Irish people see ourselves. We keep everything in proportion, including our own egos. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad quality, although it can cause mild culture shock when we’re communicating internationally.

The appropriate Irish response to a compliment is to give someone else the credit or to otherwise deflect it—and I find people from more individualistic countries tend to interpret that as us talking ourselves down, when it’s more that you don’t want to be singled out. You want to spread the goodwill.

That said, I wasn’t seeking to claim anything general about being Irish, or even about being a person, in writing Exciting Times. I prefer to show individual characters doing whatever makes sense for them, and then let readers decide if it’s an experience they share.

Ava is quite bald in her self-assessments—she’s often wrong, sometimes wildly so, but there’s an attempted honesty in her head that doesn’t come through in her conversations. I don’t think I was attempting to “challenge” that disjuncture between internal and external expression, in that I don’t know if the novel really takes a position on it. But nobody verbalises all their thoughts, so I guess that’s why Ava doesn’t.

What Irish writers or poets did you read growing up that you think anyone on the other side of the world should know about?

I loved Oscar Wilde when I was a kid, on the off chance his reputation needs my signal boost.

Marita Conlon-McKenna wrote children’s books about the Irish Famine that grabbed my imagination for several months. I became obsessed with the Famine off the back of those novels, so much so that I then read Joseph O’Connor’s historical novel Star of the Sea, which also taught me about syphilis and incest at probably too tender an age.

Emma Donoghue was pivotal in letting teenage me know that there was a place for Irish LGBT women in books. I don’t know if it’s available in translation, but I also think Máiréad Ní Ghráda’s Irish-language play An Triail is a great text for anyone who’s interested in Ireland’s history of reproductive injustice and misogyny. We studied An Triail in school, and I’ve never read anything in English that I’ve found as powerful on those issues.

How did your experiences at Trinity College shape you as a writer?

I don’t know if they did! I think to answer that question I’d need a clear sense of who I am as “a writer,” which is still a concept I’m confused by—like, does that category concern itself with my internal psychology and identity, or is it purely about the empirical work I produce?

If it’s about the work itself then Trinity didn’t shape my writing at all, because none of my current published work was written there, none of it is set there, and so on. But to the extent that me “as a writer” is about me as an individual, or about where I initially developed various themes and concerns that perhaps later emerged in my writing—I can’t say if doing something else at that age would have made me a different person, or if I would have wound up the way I am regardless of whether I’d gone to Trinity.

Like anyone just out of school, I had a lot of growing up to do; so, in that sense, Trinity was formative.

But I’ve always liked books and I’ve always liked people, so I can’t imagine a version of myself who could have done something else without encountering books and people that would have shaped me.

I was thinking about one of your recent tweets: Sometimes I’m writing something and then suddenly go: ‘am I making these characters male so they can have serious ideas about the world without people assuming I’m trying to parody them?’ As a reader, who do you think historically has gotten to have serious ideas about the world? As a writer, how do you navigate who gets to be taken seriously, and take up space in a story?

When I have my characters express thoughts about the world, it’s most often because I think that having ideas is a major part of being human, and therefore a major part of convincingly portraying humans in fiction.

I’d find it unconvincing if a character only thought about politics and philosophy, and never considered how to tie their shoes or what to have for breakfast; but I’d find it just as one-dimensional to write characters who never considered broader questions.

There aren’t many overt big-ideas conversations in my fiction; it tends to be scattergun hints about how the characters approach things, because that’s the reality of it for me.

I don’t voicenote my friends with: “Capitalism, good or bad?,” but my stance will surface as we discuss more immediate matters.

Yet I think when novels put women on those planes of thought, people are likelier to assume that the author is using those characters to voice their own opinions, or that they’re trying to make fun of them. Maybe it’s just dialogue, you know? Maybe it’s just texture. Many of my characters’ thoughts are glib or underdeveloped, as are most of the soundbites I come out with in conversation.

It’s just character development.

It’s also possible, indeed commendable, to think about things without immediately forming an opinion—but I’ve yet to master that approach myself, so I’m loath to grant all my characters a level of intellectual restraint that I lack.

I loved in Exciting Times how characters are often the beneficiaries of—and sometimes to blame for—perfectly exacting commentary on each other’s flaws. For example, when Ava says how Julian sees beyond her exterior sparkle to the interior layer of her that only clever people see. And when Edith tells Ava, “I think you want to feel special—which is fair, who doesn’t—but you won’t allow yourself to feel special in a good way, so you tell yourself you’re especially bad.” There’s that double bind of being able to learn about how people see you but also being confronted with something you didn’t notice on your own. I was wondering how you dealt with writing for—or against—this being interpreted as a coming of age novel, not just a romance or love triangle?

Yeah, I think we—or certainly, I—want to feel we’re getting the most honest version of how other people see us. When we learn that someone has deceived us, it’s jarring not only because of the deceit itself, but because it suggests that other people might be harbouring perceptions of us that would crush us if we knew.

“Please be honest with me” is often actually a request to lie extravagantly, and I think Ava definitely falls prey to that tendency.

I wasn’t really concerned with how people would interpret the novel when I wrote it, though. I don’t think there are any categories of fiction that it’s inherently good or bad to belong to.

I would find it annoying if people judged Exciting Times by whether it worked as a crime thriller or a Mills & Boon, but only because it would be a dreadful novel by those criteria and it stands a better chance of succeeding on other metrics. I’d never accept it if another author tried to make me apply a particular critical approach to their novel, so I think I have to allow other readers the same freedom with mine.

Money—making your own, being controlled by how much other people have of it, the fear of not having any, borrowing some, gifting it, chasing it, subsidising it, not knowing what to do with it—has a big presence in the novel.

Sometimes it comes up in a literal sense: a borrowed credit card to pay for drinks; other times, it’s more cultural capital, for example, profiting from listening to other people and collecting the things they tell you for later use. In the writing of this novel, did you discover if there is a normal relationship to have with money?

Definitely not! I don’t think it’s normal to have a world where survival is tethered to whether billionaires need our labour. No normal relationship with money can flow from that basic setup. We can perhaps have normal relationships with money in the sense of “accustomed” relationships with it, or “unthinking” relationships with it; but I don’t think I’ll ever really get used to the fundamental weirdness of private property.

I don’t really know what it’s like to feel normal in general, though. I’m not sure whether everyone feels as permanently alien as I do, or if that’s an especially autistic or queer experience—but in any event, the prospect of feeling ‘normal’ about anything seems so distant to me that I’m not sure I’d ever use fiction to reach towards that sensibility. I think I’m more interested in exploring ways of navigating and honouring difference while still being in the world with other people.

I loved how much Ava noticed things about language—how she enjoys parsing through it; noticing accents; picking up on odd phrases (as Ava points out: real people talk, they don’t "touch base"). How much of this was driven by wanting to reveal the benefits of holding an outsider status, and how much of it was about demonstrating the lure of being an insider; part of the club; the in-joke; the big secret?

I think the impact of that material really depends on the reader. For me, I enjoy learning about Irish English because it’s cathartic to understand why the English I read in books was often quite different to the English I heard around me as a child; why I alter my speech when I’m not in Ireland, and so on.

It feels like an outsider lens to me because it’s taking a step back to analyze what normally comes to me as a lived experience. For a non-Irish person, though, the information about Irish English in Exciting Times might hold “part of the club” appeal—the sense of getting closer to something that they hadn’t known about previously.

Language is tethered to social norms, so I also think it’s difficult to discuss phraseology without at least implicitly dealing with the unspoken aspects of how we relate to one another. There again, insider versus outsider appeal will depend on the reader.

I tend to feel like I’m getting closer to social norms when I examine them; but if your instincts are better than mine, then that same analysis might feel more like taking a step back.

This novel is set in 2018, before the constitutional ban on abortion in Ireland was removed. What does writing in the near-past, rather than the right now, or near future, allow you to do as a writer?

Well, most novels are likelier than not to be about the near-past by the time they reach readers; I finished the first draft of Exciting Times in early 2017, and I think the time-lag between then and its 2020 publication is fairly typical.

I couldn’t have set the novel much later than I did at the time. I suppose I could have edited it after Ireland repealed the abortion ban, but I don’t know if doing that would have hugely altered Ava’s consciousness; I think the scar of that law will always be there for anyone who grew up under it. I don’t know if I’d ever deliberately set something in the near-past when I began writing it.

It’s likelier, going forward, that I’ll keep giving my characters whatever political consciousness I think they would realistically have; and if the world changes after I’ve finished whatever I’m writing, then I’ll happily think of it as reflecting a now-altered set of conditions.

And it’s worth noting that awareness fluctuates—Ava doesn’t think about the level of abortion access in Hong Kong, for instance, because financial barriers become far less of a concern for her there.

Omissions are just as telling as inclusions. If I’d written an Irish narrator who hadn’t been thinking about abortion in Ireland, then that would have told us that they had the level of access to money in Ireland that Ava comes to have in Hong Kong. Having Ava never think about abortion in Ireland in 2016-17 would have “set” the novel, and “set” her character, just as much as having her consider it.

As a reader who lives on the other side of the world—and isn’t Irish, or English—but has lived abroad as an expat, what stayed with me after reading the novel was the struggle of making sense of who you are, when who you are might not be seen as useful, appreciated, or good. Ava says, "The English taught us English to teach us they were right.” How is novel writing a way to claim who you are, or challenge how much identity should dictate our creative work?

Writing novels is, in the immediate, a way for me to stop thinking about myself and do other things that I find more pleasant. Sometimes that’s creating or analyzing a character, sometimes it’s reaching for the best adjective to describe a chair, sometimes it’s deciding whether to end a scene or stretch it out a little bit longer …

All those decisions are enjoyable for me because they take me out of my immediate circumstances and into a place where I can have a bit more fun. But when you actually publish a novel, you’re constantly asked about yourself, and people often seek to make connections between you and that novel.

There’s no universal identity, so considering the particularities of an author’s circumstances can be illuminating, particularly if they would otherwise be assigned an incorrect label; I’m open about being queer and autistic mainly because I know that many people would otherwise assume that I’m straight and allistic.

So, I think ultimately, people are free to make whatever connections they wish between my identity and my work—but I don’t like being asked about it, largely because I would rather talk about things besides myself in general. I’m reading a book about pre-Raphaelite art at the moment, and I find that topic considerably more engaging.

You mentioned in the acknowledgements of your novel that everyone deserves to write books if they want to. What advice would you have for someone who might not have the odds in their favor?

I’d say focus on whatever’s within your control. There are countless inequalities dictating whether, or when, the literary establishment recognizes and rewards writers.

Before it even gets to that point, there are manifold barriers to carving out enough time and energy to finish a novel in the first place. But to whatever degree you’re able to muster the time and energy, it’s within your power to keep your head down and work on something you love.

Meritocracy is a lie in terms of eternal reception; but privately, on your own terms, you can produce something brilliant, even if it’s a paragraph a day.

That’s not to excuse the unfairness of who gets published and who doesn’t. We absolutely need to stay angry about that, and use that anger to reform the industry.

But that’s how I’d advise aspiring novelists to proceed: paragraph by paragraph.