The Close Read is a careful look at a component part of a thing we love—a single song, a chapter, a scene, an ingredient—often with some helpful commentary from the creators themselves.

I’m looking at the artifact of an image. It shows a woman visiting a Tom of Finland show, but for once the drawings lining this hallway play coy; sunbeams have turned every stiff muscle and gorge of leather into a radiant blank. Standing at the far end of the room, her form appears to fold inside the light. She was photographed by Hilton Als, the New Yorker theatre critic, author of White Girls and The Women, and the man behind my favourite Instagram account. I love it partly because he doesn’t use Instagram as most of us do: There are no photos of cats, bereft thirst traps, or aestheticized book covers, none of those tags floating above new lovers and karaoke glow to map constellations of gossip. Als has posted exactly two selfies. He never bothered to change the default icon. Like his writing, one pictures somebody elegantly reeling around a puddle.

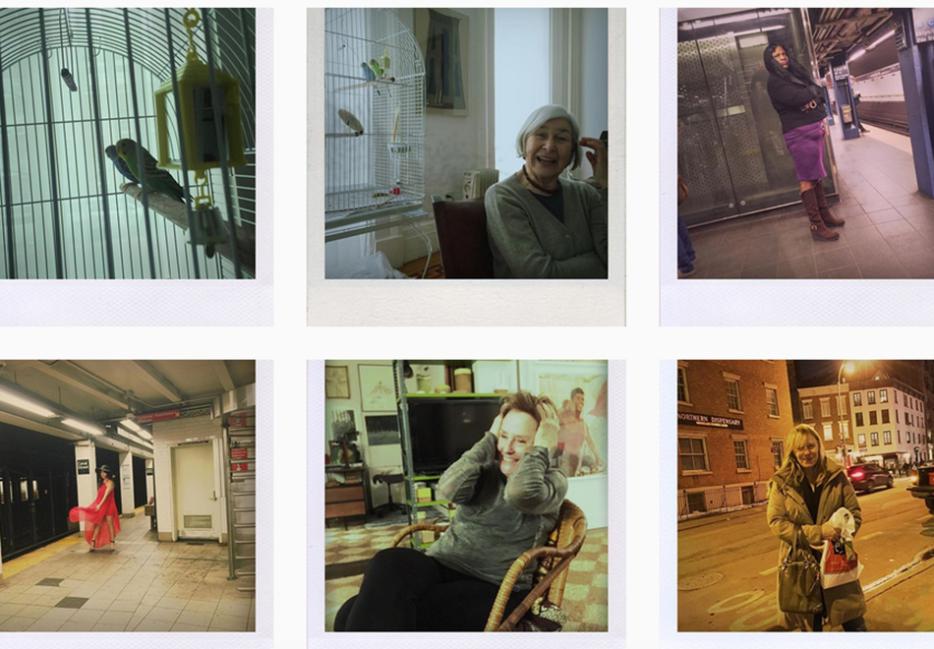

If you scroll back all the way to the beginning of Als’s Instagram feed, you can see him arriving at his style. He hadn’t found the soft, sugary light of his usual filter, which renders everything as ersatz Polaroid. The images are mundane. Then you come across this photo from Fire Island, a couple’s hair curling into one dark parenthesis. To say he captured the moment feels wrong—it’s too languid a heist. Famous people cameo on Als’s Instagram, but he never mythologizes them like Nadar or Avedon, each portrait awaiting its pantheon. Captions hold to the minimalism of a scrawled note: “Lily Tomlin. New York. 3/24/15.” Yet Als will also turn abruptly, marvelously reflective, kneeling to dig a shard of coral from the beach: “Imaginary boyfriend: Robert Mitchum. He preferred to be called an actress. He loathed being called a man's man and loathed politicians and power. Because it should always belong to the people, he said.”

Photography has been a toy for the wealthy, an artisan’s profession, an amateur’s hobby, and now finally a habitual reflex. Ever since it first offered up pieces of the world, we’ve tried to sculpt and paint them: A German experimenter figured out how to retouch negatives in the 1850s. Not long afterwards, Julia Margaret Cameron received a primitive Victorian camera from one of her daughters—the laborious process akin to painting—and set about creating pictures in liminal shallow focus, casting Alfred Tennyson as a hedge wizard and passing strangers as Arthurian knights. Als has a more modern sense of theatre, but many of his best photos seem bouncily staged to my eye, as if he’d just held up his phone and made a suggestion, or a consolation, or a dig. Whether he’s shooting a boy crowned by flowers or the artist Kara Walker’s levitating smile, they look so beautifully composed.

Why critics might be ideal photographers, according to Susan Sontag: “The person who intervenes cannot record; the person who is recording cannot intervene.” But you can’t make a record without stepping into the path of something.

The most constant presence on Als’s Instagram is Tavi Gevinson of Rookie. Tavi shows off her new jacket. Tavi spends Passover with Frank Langella. Tavi eats a sundae. Tavi looks at Celia Paul paintings. Tavi photographs Hilton. Hilton photographs somebody else photographing Tavi. Als likes using first names democratically, so that a chubby baby is known on the same terms as (say) Zadie Smith, but here words meet image with the secretive familiarity of siblings. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes agonizes over photography’s demands on his form: “I constitute myself in the process of ‘posing,’ I instantaneously make another body for myself … I don’t know how to work upon my skin from within.” Last week I posed for a photographer friend, tonguing a knife in pink eyeshadow, and at some point I realized that my usual anxiety about other people’s cameras had been filtered away with the light. It felt conspiratorial, an evil sort of trust. There’s this Instagram where Als catches Gevinson glancing from a painting towards him, recognizing, waiting.

Why critics might be ideal photographers, according to Susan Sontag: “The person who intervenes cannot record; the person who is recording cannot intervene.” But you can’t make a record without stepping into the path of something.

“What we must demand from the photographer,” Walter Benjamin argued in 1934, “is the ability to put a caption beneath his picture as will rescue it from the ravages of modishness and confer upon it a revolutionary use value. And we shall lend greater emphasis to this demand if we, as writers, start taking photographs ourselves.” I can’t say that any of my Instagram captions have done much to speed the death of capitalism. In 2016 everybody takes photographs, and we abridge ourselves accordingly, but that generates new kinds of images too, so much unstable information that our voyeurs might blink. Elsewhere, Sontag wrote: “Out of language, one can make scientific discourse, bureaucratic memoranda, love letters, grocery lists, and Balzac’s Paris. Out of photography, one can make passport pictures, weather photographs, pornographic pictures, X-rays, wedding pictures, and Atget’s Paris.” With his phone camera Als makes home-decor critiques, musings on bisexuality, possible accidents, mise-en-abyme, a study of Diana Ross, and his own Paris.

“No artist worth their salt, pain, humor, steeliness, selfishness, generosity, love, ruthlessness, or plain interest in other people and things can turn away,” Als said last year, reading an unpublished piece on Diane Arbus, whose marginal subjects were both ignored and gawked at. Arbus often gets portrayed as a silent carnival-barker, but he would not have it: “You were in conversation with your sitters, a social exchange resulting in a kind of emotional documentary that became metaphysical as that terrible and beautiful alchemy took place; which is to say the sitter, you looking at the sitter, the camera’s click, and sometimes flash.” In Als’s writing he keeps rolling off the boulder of genre, trying to slip out of imposed positions. He scribbles memoir onto film stills. Julia Margaret Cameron once testified: “I longed to arrest all beauty that came before me, and at length the longing has been satisfied.” None of Als’s Polaroids sit inside a drawer somewhere, nobody can really be said to possess them. Beauty he only considers, in that moment of the camera’s poise.