There was a dying squirrel on the sidewalk. Its sides were going up and down and when I glimpsed at it, it rolled its eyes as if annoyed. Keep on walking, I thought, and then the kid said, “Squewal. Is he dead?” Ignore it, just keep on walking. “Squewal. Mommy. Squewal,” the kid refused to move.

I decided this was an educational opportunity. So we turned around to look at it. “Yes, he’s dying,” I said. My kid’s big brown eyes beamed at me: “Is he in going in the sky?” This is where dead things end up do according to my son’s daycare teachers. My son’s grandpa, my grandma (who both died without ever meeting the kid), our cat Lucy, and the very stiff raccoon in our backyard from last year were all in the sky already as far as the kid was concerned. Now the squewal was about to join them.

The concept of death entered my son’s life early on. Mostly because of the cat, Lucy, whom he knew and who went to the sky due to aneurysm. But before that through books, specifically via Augustus who would not have any soup, got very skinny and died of starvation. The story of Augustus who would not eat his soup is by Heinrich Hoffman, the nineteenth-century author of ecstatically morbid cautionary tales, Der Struwwelpeter.

Some of the other tales in that book: A girl plays with matches and is burned to death, a boy gets his thumbs cut off with scissors (accompanied by an illustration of a boy bleeding from the stumps, worthy of the Saw movie franchise), a boy goes out in the storm and vanishes. Someone gave us Der Struwwelpeter and we read the story of Augustus to our child whom we actually nicknamed “Augustus” because he was adorably chubby, just like the fictional soup-hating boy who lost his chub and his life due to picky eating habits. Actually we only read that story to our son once or twice. We couldn’t afford to go on reading it—our child was growing and his consciousness seemed to be taking a hold. We didn’t want to give him nightmares, picky eating or not. It was better to stick to books about trucks where nothing happens except for the trucks being trucks. But as our son’s awareness expanded, the questions about life and death came. And what’s better than books to ruin a child’s innocence?

See, if it wasn’t for books, our child could probably spend the rest of his childhood in a cotton-candy-cloudy bliss of ignorance but (un)fortunately, no. Take the themes of a few of his current favourite works of kid lit: loneliness, heartbreak, the existential quest for meaning, crime, and murder. There are, of course, plenty of books wherein the action mostly revolves around whether he can guess that Alligator starts with the letter “A”, but those are rarely the repeats (and when I say “repeats” I mean they are requested night after night after night afternightafternight…). The most popular works at our house deal with serious stuff. And they’re not some outdated, old-school cautionary tales of chopped-off thumbs—these are recent bestsellers, raved about by sensitive parents everywhere, gifted to young children by grownups who seem to be hinting at many terrible truths about life (life is a bitch and then you die).

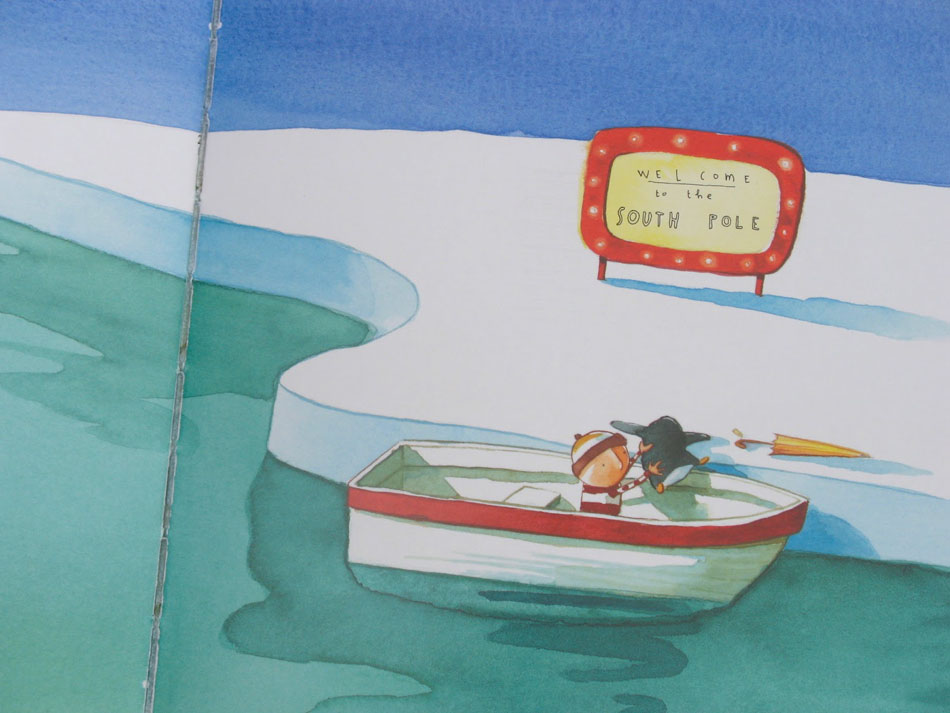

One of the early favourites at our house was Lost and Found by Oliver Jeffers, the tale of a boy who finds a penguin that he, somehow ignorantly, deposits at the South Pole only to realize that he’s made a terrible mistake. Although, let’s be honest: this is partly due to the penguin’s passive-aggressive ways. It turns out the penguin didn’t really want to be separated from the boy, yet he helped pack their boat to the South Pole and everything. After much stress and confusion, the two friends eventually reunite.This is like one of those shit-tests like when you’re supposed to figure out that your girlfriend wants you to ask her to move in together—even though she keeps telling you how much she loves her apartment.

Recently, we were given another Jon Klassen book, This is Not My Hat, which deals with similar themes (crime, punishment), except it’s even more sinister in its execution. The story is narrated by a small fish who gets eaten by a big fish, after being betrayed by another character (a crab). The fish-narrator is also a hat thief but seriously, is that big enough of a crime to pay for with your life? Who can really tell. My son is older now so he finds the murder (which happens off-page by the way) quite exciting. It seems he has formed no attachment or sympathy toward the narrator that has stayed with him throughout the story. He looks up at me after we’re done reading it and grins smugly, “He’s in his tummy now!”

“But do you think he should’ve died?” I ask. Enthusiastic nodding. My son is not a sociopath. He is three years old. And, thanks to books, he’s getting to know the world—the happy and the sad bits of it, the ones that have to do with trucks being trucks and the ones to do with death.