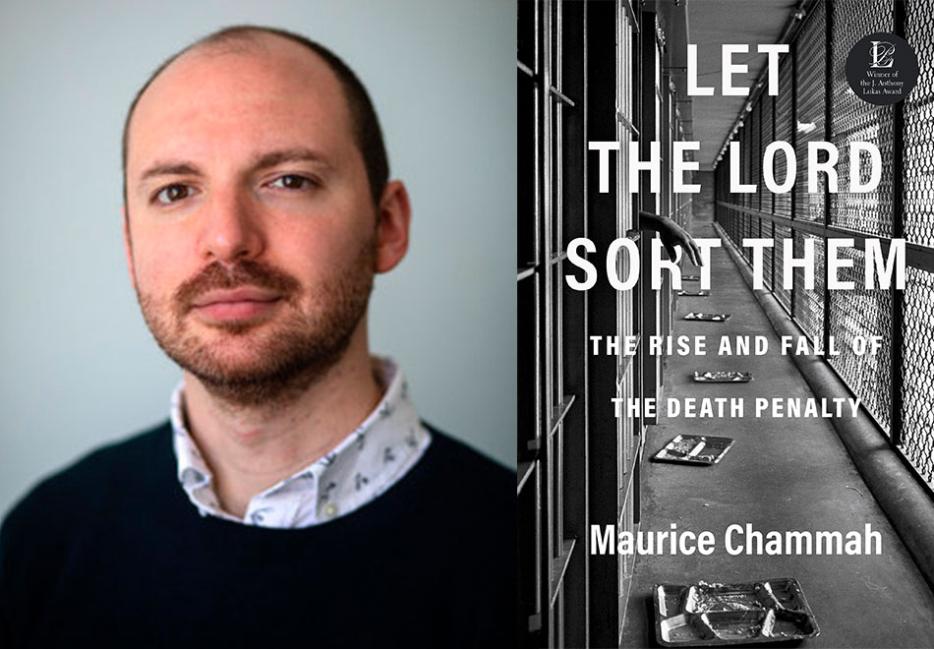

Maurice Chammah’s debut book is a heart-rending history of capital punishment in America. Centred around Texas, Let the Lord Sort Them: The Rise and Fall of the Death Penalty (Crown) throws light on the Walls Unit in Huntsville, the site of the state's execution chamber. Texas has led the way in the use of lethal injection; since 1982, 570 people have been put to death by the state.

Chammah, an Austin-based journalist and a staff writer at The Marshall Project, tracks this macabre legacy by profiling individuals sentenced to death as well as the lawyers who represent them. He also looks at the lawmakers and politicians who sanctioned the rise of draconian sentencing through legislation. A compassionate and fastidious storyteller, Chammah questions the prioritization of retribution over redemption and confronts the inherent violence of the American criminal justice system.

During the Trump administration's final days, as a blitz of federal executions were carried out, I spoke with Chammah about his new book and the future of capital punishment in America.

Andru Okun: I’d like to hear about your connection to Huntsville, Texas. When did you first become interested in the penitentiary there?

Maurice Chammah: The genesis of Let the Lord Sort Them and my general interest in the death penalty goes back to 2010. After I graduated college, my first job was with a small non-profit [Texas After Violence Project] that was collecting oral histories related to the death penalty. I remember driving with a colleague to Huntsville on the day of an execution and standing outside, watching the guards put out yellow caution tape around the prison and seeing a small group of anti-death penalty protestors. At the time, I had been thinking about the death penalty in very abstract terms, but then it hit me that this was the place. Behind the prison wall, they were actually carrying this out.

Over the next five or six years, I’d go back to Huntsville pretty often, usually for some kind of reporting related to the prison system. I got to know the town. Many people that live there work in the prison system, but the death penalty and executions are really an afterthought and they don’t consume a ton of bandwidth among the residents. Blocks from the prison there’s a little diner that’s very famous called the Cafe Texan. In my research for this book, I discovered there’s this almost ritualistic article where a reporter goes to the Cafe Texan and learns that no one in the cafe has any idea that an execution is happening a few blocks away. There’s drama in that, and I feel like it’s symbolic of the larger picture. Capital punishment has been going on for so long and occasionally it hits the news cycle and we pay attention to it, but it can also recede in awareness, even a few blocks from the place where it’s happening. If you know about prisons, Huntsville is a famous town, but to everyone else it’s just another small town in East Texas.

You write that Americans have always viewed capital punishment with a degree of ambivalence. What do you mean by that?

At a big symbolic level, the death penalty is the way we say as a society that some people are irredeemable. It represents the turn towards punitiveness that the criminal justice system took over the last forty or fifty years. We’ve only executed a small number of people in the grand scheme of mass incarceration, but the fact that we have the death penalty has made it more acceptable to send people to prison for the rest of their lives. As individuals, we have impulses towards both punishment and mercy. Defense lawyers like to say that none of us would want to have our lives be shaped by the worst decision we ever made. We’ve all made decisions that we regret, and we feel lucky that we weren’t held fully accountable. Our ambivalence shapes the way we view capital punishment, and it also shapes the way we view mass incarceration more broadly. We want to throw people away for the rest of their lives, but we also have a real curiosity about the people we choose to lock up, wanting to know who they are and how they ended up there. There’s a whole genre of true crime that both gawks at the terrible things people have done while also expressing a curiosity about the psychology behind the acts. Part of that is driven by wanting to understand if evil exists and what it looks like if it does. In our better moments, I think we’re motivated to see around the corner of that evil. We’re all human, and we’re all capable of terrible things. In the effort to understand the psychology of people we deem “the worst of the worst,” we’re also trying to understand if there’s a human we can feel merciful towards, because we also want to feel merciful towards ourselves.

How do you think America’s history of lynching is connected to capital punishment?

Over the course of American history—having enslaved an entire group of people and then built an elaborate architecture of inequality based on skin colour—we often use race to close off the mental doors to mercy. In the era of Jim Crow, there was a rash of lynchings across the South. One of the points I make in the book is that it happened in Texas as much as any other Deep South state. Texas has had a cultural mythology that has allowed it to escape an association with the Old South. I think that has been detrimental to our state’s culture—it’s meant that we’ve gotten a pass on having to reckon with these things. Lynchings are the most violent and extreme example of the way that Black people and other minorities were treated as less human than white people.

As you get into the contemporary era of the criminal justice system and the death penalty, it’s not quite as stark. There isn’t an overt idea that these Black men are monsters and evil, that they need to be held in bondage and fear. In the death penalty cases throughout the ’80s and ’90s, you can see in the trial transcripts that that kind of racism is more subtle. It’s the language of, “They are taking over the streets.” During the Central Park Five case, prosecutors, politicians, and Donald Trump were raising the specter of gangs of young minority men, rampaging around and beating, raping, and killing primarily white women. That was the dominant story, and it flows very naturally from our country’s older, more explicit racism.

How would you say this more veiled form of racism informed our ideas around evil and retribution?

Evil is not always used for Black and Latino defendants; there’s also a cultural myth around the white, evil serial killer. But a big part of what was fascinating about this research is that death penalty cases are so rich with symbolism. They’re high-stakes battles of life and death, so in the trial transcripts there are evocations of deep strains of American culture. In many cases, Christianity creates the atmosphere for people to be called evil. Evil is a term that Americans are pretty ambivalent about. There’s plenty of Americans that have a deep, theological commitment to the idea that there is evil in the world, but it’s a little harder when you get to the idea of people being evil. Can a person be evil? Or is it just their actions that are evil? There’s a lot of tension in these questions. In a lot of American churches, generally the concept is, “Love the sinner but hate the sin.” People can do evil things, but no person is evil. At the same time, in these death penalty trial transcripts, there are descriptions of people as evil. I think many people are ambivalent about whether a person can actually be evil, because it’s a hard thing to admit. Our impulse to empathize with fellow humans is pretty strong, but there are times where a wall is put down between us and another human—racism or a word like evil can be that wall. And sometimes a word like evil along with racism can form a really strong wall between us and a fellow human. Defense lawyers have developed the ability to get people to see around that wall, to get the kinds of people on juries who are willing to do the mental labor to empathize with people, no matter how bad their actions were or what their race may be.

I want to return to Texas mythology. You commented earlier on how the state’s failure to acknowledge its history makes it difficult for reconciliation to happen. If that reckoning with the past had happened, do you think Texas’s relationship to capital punishment would be different?

It’s hard to prove a counterfactual. What I came to see is that Texas’s intensive embrace of the death penalty was overdetermined. There were all of these forces—legal, political, cultural—that conspired together to perform an outsized role, and at a certain point the effect became exponential and fed on itself. The more comfortable a prison system is with carrying out executions, the more executions that prison system ends up carrying out. One scholar [Brandon Garrett] has compared this to muscle memory. I don’t think that you can prove that if Texas addressed its obsession with Wild West culture that it would totally undo the death penalty. That said, the era in which the death penalty has declined coincides with Texas starting to lose that Wild West mythology. Certainly, plenty of Texans still like to think of themselves as cowboys living on the frontier—there’s a real element of that in Texas culture. But at this point, most people that live in Texas live in big cities. There’s a new vision of Texas that is much more cosmopolitan and urban, that is interested in empathizing across racial, cultural, and gender lines. I think that’s at least part of the decline in the death penalty. It’s a less saliently political thing; legislators and district attorneys don’t campaign on it as strongly. We’ve had a whole run of more progressive district attorneys get elected in major cities on platforms to use the death penalty less often. The fact that people voted them in says something about where Texas is going and how far it has come. I recently heard one district attorney admit that it’s hard to even find twelve jurors that can say they would give someone the death sentence. There’s still plenty of Texans that support the death penalty—well over fifty percent, even. But it’s a little harder, year-by-year, to get twelve of them in a room to say they’re all comfortable with sentencing someone to death.

In 1982, Charlie Brooks became the first person to be put to death by lethal injection. Before this, Texas went nearly twenty years without an execution. But after Brooks, there was a steep rise. Can you explain this shift?

The story of the shift actually begins in the 1970s. In ’72, the Supreme Court said that the death penalty violates the constitution and the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. This followed a decade of declining popularity of the death penalty and also really active efforts by civil rights lawyers, specifically the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund. Throughout the ‘60s, they managed to stop executions. People were comfortable with no executions happening, and it looked like the death penalty would disappear. But once Americans were deprived of the death penalty, people began to speak out in favour of it. I write in the book that this comes as part of a larger backlash to civil rights protections. The death penalty is symbolic. People started pushing their legislators to write new laws. So, in ’73, Texas wrote a new law and in ’76 the Supreme Court looked at the range of laws that legislators have passed throughout the country and they approved some and rejected others. Texas’s law was accepted even though it looked a lot like other laws they rejected for being too harsh. So, Texas snuck in with this law and that’s a big reason why more and more people started to be sentenced to death. After the first lethal injection in ’82, Texas slowly carried out more and more executions, and this is where the muscle memory started to kick in.

You write that “by the late 1990s, retribution had become an organizing principle of the American criminal justice system.” Would you say Texas set the precedent?

It did. There’s a great book called Texas Tough by Robert Perkinson that talks about the state’s prisons. The idea is that Texas pioneered these very punitive ways of organizing its justice system for people who have been convicted. There’s more solitary confinement, more hard labor in the fields. It’s a really terrible place to do time. I see executions as the pinnacle of that system. If you believe that some people forfeit their rights to be human because of what they’ve done, the death penalty is the ultimate expression of that idea. In a cultural sense, Texas led the way. In a very practical sense, because they figured out how to execute people smoothly, efficiently, and often, other states started to send prison officials to study the Texas model.

I appreciate that you took time in your book to describe the living conditions of incarcerated people. What were some of the things that stuck with you when learning about day-to-day life on death row?

There have been two death rows in Texas. In the ’80s and ’90s, it was at a prison called the Ellis Unit, which is also in the Huntsville area. It was one of these prisons that really evoked the Old South and the plantations that these prisons replaced. Men would work in the fields and do harsh, punitive farm labor. But the death row prisoners were held in solitary confinement; some were given a little more freedom and the opportunity to work in a factory indoors. I found that the conditions for Texas death row prisoners mirrored the larger story of American incarceration—in the ’80s and ’90s we were increasingly warehousing people, but we were willing to allow people to work in factories or receive art supplies.

At the end of the ’90s, as America shifted towards solitary confinement and warehousing people in a stricter sense of the term, Texas changed its death row to a different prison in Livingston called the Polunsky Unit. That’s where death row prisoners in Texas have been for the last twenty years and it is horrible. It is all solitary confinement with people locked in their cells for 23 hours a day. Prisoners can barely communicate with other people. One detail that stuck with me is the only human touch a death row prisoner gets is when they stick their hands through the slot in their cell door and the guard places cuffs on them. A lot of men with mental illness became psychotic as a result of these conditions; even men who were relatively healthy when they went in started to have psychological problems. Prisoners see their family less, it’s harder to use the phone, and letters are read by prison authorities. It’s just an awful place to live.

Even in that horrible place, you have men who manage to play Dungeons & Dragons with each other. Several death row prisoners corroborated that they managed to doctor their radios into walkie-talkies so they could talk with each other. There’s a culture of connection and encouragement that I found heartening, even in such a dark place where people are struggling with mental illness and depression.

Let the Lord Sort Them reports on the fine details of legal proceedings. How familiar were you with the laws around capital punishment before taking on the project?

At the oral history non-profit I worked at before becoming a journalist, the director and the founder were both lawyers. The founder, Walter Long, defends people on death row. We would have long conversations where he would explain the complexities of death row cases. At the trial stage, it’s relatively straightforward. The human drama of the system plays out in the complicated gauntlet of appeals. When defense lawyers in the ’90s were sparring with state lawyers over whether or not an execution was going to happen, they argued about very technical details, but there were also a lot of accusations about faith and personal enmity. One lawyer told me he almost got in a fist fight with a prosecutor at a bar in Austin, which may have been a bravado story but seems plausible enough, given how much I’ve heard about how these people hate each other.

The Marshall Project is not afraid of complexity, so I got to do a lot of reporting that gave me a familiarity with capital punishment. In writing the book, my editor Emma Berry (who was amazing) encouraged me to introduce the ideas in a way that put the reader in the shoes of a lawyer or a law student, to teach the reader by showing the character learning this material. The implications of the complexity came to life that way.

We’re speaking during the last days of Trump’s presidency. What do you make of his push to execute people on his way out of office? And what do you think the future holds in terms of capital punishment in America?

One lesson that I continually returned to as I worked on the book was that the death penalty is in decline. The number of factors that would have to come back into play for it to have a true resurgence are so many that it feels unlikely. That said, the executions under Trump—he’ll have carried out roughly a dozen by the time he leaves office—I think we’ll look back on it as the last gasp of capital punishment. It won’t be the last gasp of white supremacy in America or the many other terrible aspects of our society that the Trump presidency has brought to the forefront, but the number of people who are sent to death row every year is dwindling to single-digit numbers, and the number of executions is going down.

There will still be debate about the death penalty in rare cases like Dylann Roof or Dzhokhar Tsarnaev; there will be one-off acts of atrocity that shock us and make us think that maybe the death penalty has a place in our society. There was a big drop in executions during the coronavirus (with the exception of the federal executions) because they were harder to carry out. The coronavirus, which has killed so many people, has shown us that the death penalty may ultimately be a luxury that we don’t want to afford any more. We like to have the death penalty in theory, but when it comes to putting it into practice, we’re ambivalent about really doing it. There are hundreds of people on death row who will likely never be executed and instead live out their lives. They could have been sentenced to life without parole, but they won’t be because we have this commitment to the idea of the death penalty even if we don’t want to carry it out. It feels like a relic of our earlier selves.