I don’t really recall when I first heard about Torrey Peters and her work. Her novella Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones hit the internet around the time I began transitioning. The first year or so of trying to live in the world as a trans person is incredibly annoying, and one of the ways of coping with that is to talk shit with other trans people. After extended grumblings about the myriad ways in which cisgender people had been obnoxious in recent memory, some trans girl would slyly reference Peters’s novella, hoping that the others would respond with blank faces. Some girls really loved to be the one to introduce you to the book. Okay, so basically it’s this post-apocalyptic book about a trans girl who gets revenge by turning everyone on earth trans ... yeah it’s super wild, you have to read it, I’ll send you my PDF.

The provocativeness of such a premise was exhilarating—but it wasn’t the idea of the story that excited us so much as the act of writing and publishing it. What gave Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, along with Peters’ other novellas Glamour Boutique and The Masker, such cult-like status among trans people was the way they didn’t care to make concessions to cisgender society. These were stories that were developed and circulated without any interest in pandering. They had no interest in proving the inherent respectability or naturalness of trans women. They were simply fun—smart, snarky, filthy, occasionally deranged fun.

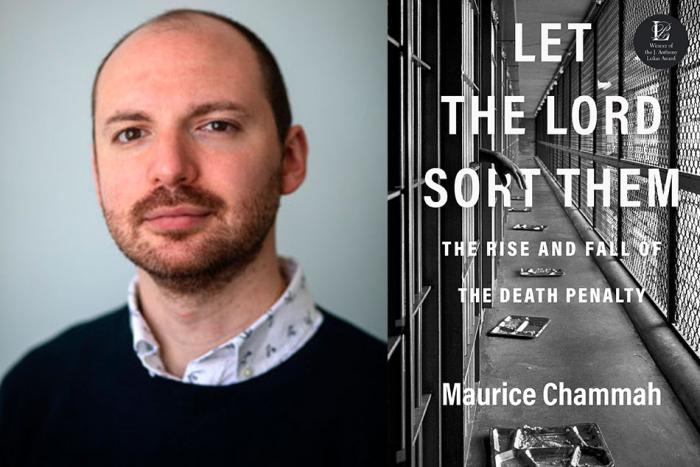

With Detransition, Baby (One World), the Brooklyn-based trans woman steps into mainstream publishing. If fans are worried that this larger platform might mean a more constrained speaker, the premise of the story should put their anxieties at bay. The novel flits between the interlinked lives of three young Brooklynites: Reese, a trans woman longing for motherhood in between destructive relationships with scuzzy guys; Ames, Reese’s former girlfriend who detransitioned to live as a man; and Katrina, who finds herself in a really weird situation after becoming pregnant with Ames’s child.

Witty, exhilarating, and terribly smart, Detransition, Baby is the idea of the “trans novel” turned on its head. I had the opportunity to speak with Torrey Peters over the phone about her new book, the cultural place of trans literature, writing on Adderall, and taboos.

Nour Abi-Nakhoul: The first thing I wanna ask you is: what are you doing to get through the pandemic?

Torrey Peters: My girlfriend and I found this old, one-room, off-the-grid log cabin in Vermont. It has no water, no power, and no septic. It was some kind of hunter’s shelter that had been abandoned for about 12 years. Our COVID project has been basically making it habitable as a kind of glamping site. So, we've been going up to Vermont a lot and just being in the woods, disconnecting from the internet and stuff. And honestly, if you're in the woods with no power or water, and just an outhouse, it feels like things are the same whether there’s a pandemic or not. You're just thinking about making a fire in the stove and how you’re going to cook your food, which has been a pretty good escape.

Detransition, Baby is such a city-bound novel, it’s interesting that as you finished it you decided to retreat into the rural.

I think for years a lot of trans people I know had an urban lifestyle, because you had to be in the city to get your hormones and your community and all that. As people are able to get hormones and find community in other ways, I feel like a lot of my friends are moving to more rural places, that they're able to find sustainable ways of living. I wonder if the pandemic accelerated something that was already happening with trans people.

Do you have any plans of writing a more rural-bound novel?

My novella Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones was a post-apocalyptic story, and I had thought about expanding it into a full-length novel. Being in Vermont made me think about what it would be like to be trans in a post-apocalyptic world, to be trying to make a fire and trying to make it.

It seems like you incorporated your novella Glamour Boutique into Detransition, Baby. Do you have plans to go back to other past works and build them into bigger stories?

There was a time where I had envisioned making Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones into a cycle. I wrote it in 2016. It was about T4T [trans for trans relationships] and conflict within trans communities, and also how trans people can save each other. After I wrote it, I felt like I had a lot more to say about those topics. It’s a bit of a narrow view of trans women. Both trans women are white, and both come from a similar sort of scene. I had thought about including other people from a broader spectrum of the trans experience in a longer form and including the people who are adjacent to trans people, like the men who hang around trans women. How all these people end up creating a social world that has a lot of divisions within it. That’s the world in which I travel, and in which most of my friends travel.

And what about with Detransition, Baby—can you guide me through how the story came into being?

I had initially started writing novellas as a project with other trans women in Brooklyn. At the time, Topside Press was publishing a lot of trans women’s writing. But it was the only game in town and not everyone could get published on it, so it ended up feeling pretty contentious. I was like, what if we all just self-published our own work? The novella was an appealing length, because I was thinking that a lot of trans women live in pretty precarious situations—the amount of work and money it takes to write a full-length novel seemed like too much. With the novella, everyone could write one every three or four months. And it could be a conversation where we’re all trading them with each other.

I bought a subscription to Adobe Suite and said anyone who wanted to use it could. I bought a subscription to Lynda, which has instructions on how to use InDesign and stuff. I was hoping that there would be a big flourishing of trans women’s novellas. That didn’t really happen.

At the time I was hoping other people would emulate these novellas, and I was planning to have a cycle where I would do novellas about trans issues in different genres. Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones was post-apocalyptic, The Masker was horror, and I started Detransition, Baby thinking it was going to be a novella in a melodrama soap opera style. But the thing about soap operas is that they’re really long! So, it kept getting longer and longer.

I had a breakup that was a real heartbreak for me while I was working on the book. And I thought, I had the skills to publish whatever I want without waiting for anybody. So, I took a chapter that was a little different than the rest of the tone of the novel and published it as a standalone. That became the novella Glamour Boutique, which I made available for a couple years. Then I thought I would actually rather people read that story in the context of the full novel.

Why make the switch into mainstream publishing?

I think that the time that we're living in is different. In 2013/2014 when Topside was happening, you couldn’t get the time of day from the publishing industry. They didn't care to hear the way that trans people talk about ourselves to each other; they wanted to hear a trans 101 for cis people. I think that to some extent that’s still true, and there’s been a bit of a regression in the last year or two. But in 2018, which is when I started shopping the book around, it felt disingenuous for me to say that the publishing industry doesn't do anything for trans people. When I looked around, there were editors at Condé Nast publications who were trans, there were reporters at Vice Magazine who were trans, Pose was winning Emmys. There had been so much trans media that included trans voices, that for me to stick to a viewpoint that this industry doesn't include us didn't feel like it was reflective of the situation. So, I thought maybe I could get some of the things that I think into mainstream publishing. Same as with other marginalized literature, the literature is a lot better when you’re speaking within the group and everybody else can keep up.

Reading Detransition, Baby, a lot of the time I was struck by how it was an intimately trans novel. How did you balance that with the reality that a lot of cis people will inevitably be reading it?

When I think of my audience I think of trans people first. The guiding star for me was Toni Morrison, who said she writes explicitly for Black women, and everyone else can keep up. That looked to me like a model for how you do this. I want to write about real pain. I want to write about what’s really funny; my experience is that if you do it, everybody else does want to keep up. People read literature for a good story, and if you’re slowing down your story by having it be 50 percent explanation and 50 percent story, that’s just not as good a story.

That said, I explicitly dedicated the book to divorced cis women. As I was writing it, I was reading a bunch of work by divorced cis women as a metaphor for transition. I was looking for ways to think about a life with a major change in the middle of it, and I found those models in the writing of divorced cis women. They have to start their lives over, change their names, not get bitter or reinvest in illusions. So, there are a whole bunch of people I’m addressing with this book, including cis divorced women. It’s not an identity address, but more of an affinity address.

Detransitioning is a bit of a taboo subject. Why write about it?

There are two reasons: one is that I feel that the detransition narrative has been taken from us by anti-trans people. They don't own it, and I don't want to cede it to them. It’s not their story, so they shouldn't get to tell that story and they shouldn’t get to tell what it means. I haven’t personally detransitioned, but it’s always looming as a possibility. There have been times in my life where it’s been really hard to be a trans woman and I’ve flirted with detransitioning. It’s my story and I don't agree that anybody else can make that story taboo.

The second thing is: I think transition narratives have become overdetermined. People expect a certain sort of arc when they read a transition story. The detransition story actually does a lot of the same work as a transition story, it just feels unfamiliar to people, so they read it with fresh eyes. By making Ames detransitioned and living in a state of dissociation, I could talk about the place of people who aren’t presenting as women without it being a story that people brought a lot of preconceptions to. I know a lot of people who live as male and have never transitioned but who identify as trans women. If I talked about them as closeted and too afraid to transition, that story is so overdetermined that no one’s going to pay attention to the character. They’re going to think they already know what’s best for that character.

What was your writing routine like while working on Detransition, Baby?

It changed about halfway through. For the first half of it, I would work different jobs to cobble together five or six days when I’d have nothing to do. Then I would just take Adderall and try to write as much as I could. Halfway through the book I thought it wasn’t sustainable. It was too pressurized. I quit taking Adderall and I started meditating. I get embarrassed when I tell this to people, but I would meditate for like 20 minutes and try to write for an hour or two. I can see a difference in my prose between the two. When I was doing the pressurized version of it, I would get to this deep place, but it wasn’t funny or loose; it was so tight and urgent. After switching to the other way of writing, I think I got looser, a little funnier; things got a little less desperate or intense.

What are some things that you've read lately that have been exciting to you?

One trans book I’m really excited about is called Lote by Shola von Reinhold, a Scottish-Nigerian writer. The book is about uncovering the figure of the Black queer dandy in the ’20s. There’s this really serious project behind the book, but there’s such an incredibly dazzling rage within it. It's so funny, and it’s written in a dandy, decadent style that’s just lovely.

Another is Time is the Thing a Body Moves Through by T. Clutch Fleischmann. Clutch is a friend of mine so I’m a little biased, but I think that everyone should read this book. I talk a lot about Imogen Binnie’s Nevada as being formative for me in what can be talked about in trans women’s writing. Clutch writes from a non-binary perspective, and I think this book should be equally formative for people.

And then there’s a book coming out called Darryl by Jackie Ess. I would say it’s a trans book, even though there aren’t any explicitly trans characters in the book. Jackie Ess is a trans woman, and she’s written a character who’s a white cuckold guy in Portland. She talks about the journey of sexual awakening of this cuckold. I think of Jackie’s writing from a place where a trans worldview has left the boundaries of only being for trans people. Now it can be applied to other stories and used to understand things about gender that wouldn’t otherwise be visible.

Can you expand a bit more on what you mean by a trans worldview?

I'll go back to Imogen Binnie; Imogen was quoting [feminist writer] Joanna Russ, talking about how marginalized literature goes through different stages. The first stage is sort of like looking for acceptance from a mainstream so far, like, we're just like you, you should accept us. That would be a novel like Jan Morris’s Conundrum, like in the ‘70s, just kind of like, we’re just women, just like everybody else. The second stage is, we’re nothing like you, die cis scum, but still really defined by the cis gaze. And then you have the third level, which is maybe the T4T level, we don't have anything to do with you, your gaze does not define how we interact.

But I think that there's a fourth level, which is when the terms that are set by trans people begin to impact the viewpoint of the mainstream. We saw this with queer thought, where suddenly straight people could only understand themselves through heterosexuality. When you hear straight people talk about their sexuality, they're largely using a worldview that was defined by queer people. I think that something similar is happening with gender. You have books like Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, which is about a pregnancy that you couldn’t really call a trans pregnancy. But Nelson understood her pregnancy through trans terms. I hope that Detransition, Baby is also at this fourth level where trans thought is applicable to things beyond trans bodies.