Shortly after Oprah Winfrey Tweeted the following inanity from her diamond encrusted iPhone—Just wrapped with @lancearmstrong More than 2 1/2 hours . He came READY!—I took a subway ride across the length of Beijing, from Sanlitun to Haidian District. I emerged into the brumal morning with the Tweet clanging in my head.

He came READY! insisted Oprah. Nothing better brings home the theatrical aspect of the weepy televised confessional more than those five capital letters, followed by that exclamation point. After all, Lance Armstrong always came ready. He came ready to races as a young triathlete; he came ready to chemotherapy as a young cancer patient; he came ready to his eighth Tour de France as a doped up cheat. If he were not so perennially ready, he’d be gracefully retired and successfully reinvented as an ESPN commentator, or the governor of Texas, or both. Instead: the inevitable Oprah interview, and an American life that is beginning to defy all reasonable narrative precedent—a Haratio Alger Jnr. who came from nothing and became Sauron on a bicycle.

Anyway, Beijing. I found the man I was looking for inside a coffee shop adjacent the Su Zhou Jie station, hiding in a booth near an emergency exit. Jia Ping is a human rights lawyer in a country that isn’t particularly supportive of his vocation. And while he is an expert in health law, Jia’s think tank advocates for greater transparency in all governmental affairs. In terms of his personal welfare, he walks a very fine line. He is a star at Davos, but he’s bupkes in the corridors of power in Beijing. He buries his outrage by drafting a body of work he hopes one day, in a progressive China, will amount to some sort of a legal framework.

I meet men like Jia Ping all the time, mostly because my professional life plays out in the swamp of developing world corruption. “The Latin word corruptus,” intoned an architect I interviewed some years ago in Namibia, “from the root ruptus. Rupture, break down, rot. Corruptus—promoting the conditions for the rotting of.” Like Jia Ping, the architect was battling a disease at the core of his society, sickening as it does every single aspect of public and private life. The book I am currently co-authoring is ostensibly a work of investigative reportage on Africa’s massive growth spurt, powered in no small part by the involvement of the Chinese. But there are times when I think of it as a tragedy detailing the effects of corruption on men like Jia Ping, and the downtrodden folk they fight for.

“In India,” Jia told me, after we had settled, “when I go through customs, I must pay some little thing, some small money. That is the corruption in India—always, you have to pay some small thing to some small person. In China, I don’t think that as a foreigner, you will ever have to do this. [Jia is only partly correct—as a white foreigner, I’m fine. But I know that airport agents routinely fleece black Africans at Guangzhou airport, and in other Chinese trading centres.] In China,” Jia continued, “the corruption is systemic. By which I mean that it is cooked into the system. It is how life is lived here. People with connections get everything, and people with no connections—who don’t work for or with the government—give everything. That is how power works, how it is concentrated, manipulated.”

By this point, you’re probably wondering what any of this has to do with Lance Armstrong and Oprah Winfrey. Quite a lot, actually. Because as a cyclist who has spent the better part of my adult years racing and thinking about bicycles, and as a writer who has spent the better part of my professional life in the developing world, I have found that cycling serves as a metaphor for just about everything, but especially for how easily an organizational system can rot from the inside. Or, conversely, how difficult it is to stem the rot.

I don’t mean for a second to equate the miseries the Chinese or Zimbabwean or Saudi Arabian governments visit on their people with the travails of skinny men in spandex. But I do mean to learn from the spectacular maelstrom that is Lance Armstrong Inc., because I believe that his particular stripe of rottenness has plenty to teach us about how power, backed by lots of money and oodles of self-righteousness, can be a force of almost unlimited destruction.

*

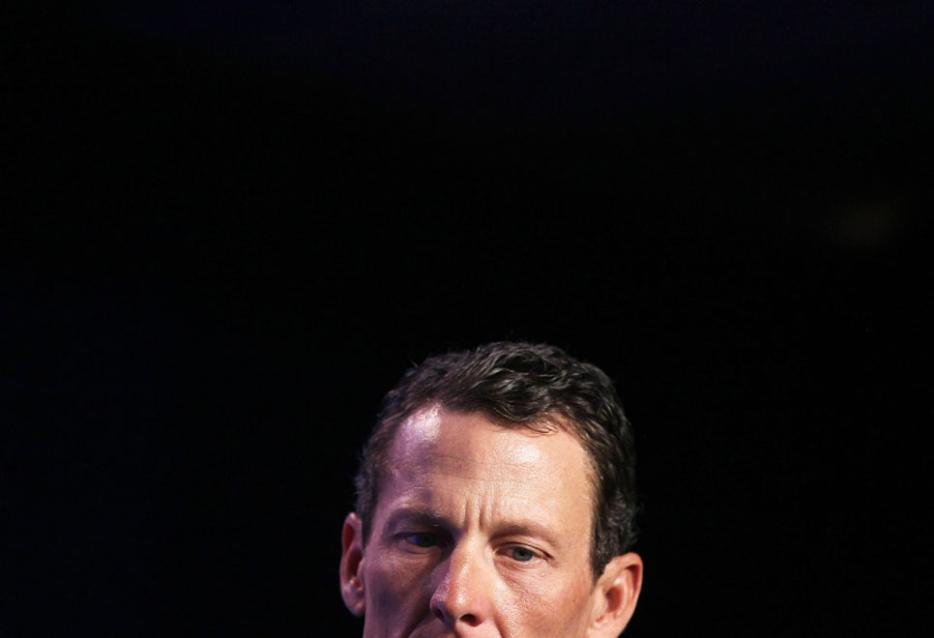

So, I was thinking of Jia Ping when I sat down to watch Armstrong bleat his confession to a talk show queen. I was also thinking of Lance’s sharp cheekbones, and his hard dead eyes. For me, he has always evinced a certain type of evil: unchecked acquisitiveness. Enough was never enough. As one of his apologists recently put it, in a blog post that Armstrong Tweeted to his millions of followers, “He was ambitious, ruthless, highly talented, tough, he knew how to lead his teammates and intimidate his rivals to make sure he won. But is he any different from a President, an army General, a corporate leader of industry, a career politician, or any other sporting great?”

A fun trivia game would be listing all of the Presidents, army Generals, corporate leaders of industry, career politicians and sporting greats that Lance is indeed different from. But for now, we must concentrate on the task at hand: Lance Armstrong is on TV to ask the people for forgiveness. And the people will judge his every tic and eye-flutter. If he weeps with the right amount of moisture, he will be brought back into the family of celebrity commodities, where he can sell his brand of win-at-all-odds boosterism to the millions of cancer patients who will follow the millions he has preached to already.

But mostly, I was thinking of Jia Ping. I was thinking of him because this is exactly the sort of Bullshit River he tries in vain to dam every day. He’s not so different from Betsy Andreu, the wife of cyclist and former Lance BFF Frankie Andreu, who was one of the first to bring the Postal Service conspiracy to light. Armstrong did all he could to discredit her—he went after her with the viciousness that any “army General” or “career politician” would have. (But he will not come clean on calling her fat. For a cyclist, the “F” word is a verbal thermonuclear device—in a version of MAD, it’s great to have in the arsenal, but it’s strategically impossible to use.)

CNN made the wise move of recruiting Betsy as a sort of play-by-play analyst for the Oprah interview, which was advertised as no-holds-barred, but was in fact many-holds-barred. It kicked off well enough—with a brief yes-and-no question period, in which Armstrong admitted to using several of the performance enhancement substances he actually did use in order to win his seven Tour de France titles. But the moment Armstrong started using full sentences, the equivocations began. Yes, Armstrong did get to the nut of the problem only minutes into the interview: “This story was so perfect for so long. You recover from the disease, you win the Tour de France seven times, you have a happy marriage, children—its just this”—and here Lance, with his genius for oratory, pauses for a millisecond—“mythic, perfect story.” In other words, Armstrong was an amazing product, and that product had almost unlimited potential, and was worth protecting at any cost.

So far, so truthy. But then Oprah asked, “How did it all work?” and Armstrong answered, “I viewed it as very simple.”

Lie. He correctly understood it as a vast conspiracy involving numerous banned substances that, in order to have the intended effects, needed to be administered by a team of very expensive sports medicine professionals, who also force-fed them to teammates so that they performed well enough to ensure Armstrong continued to win, all the while intimidating those who might be tempted blow the whistle (which is to say nothing of keeping cycling’s governing body on side by promising them a steady stream of sponsorship money, baksheesh and the Holy of Holies—the American television market.)

The 1,000-page so-called “Reasoned Decision” treatise, released by the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) last year, is one of those rare legal documents that carried the moral force of great literature. Compiled under the aegis of Travis Trygart, the USADA’s implacable chief executive, there is nothing in the document that is up for dispute—it effectively brought Armstrong’s long run of mendacity to an end. It’s also how we know Armstrong was lying when he told Oprah that he didn’t dope during his comeback in 2009, because we know that he was making payments to crooked dope doctors over the course of that year.

But rounding back to Betsy Andreu. The interview's greatest omission—and what is an admission but a lies shadow?—is when Armstrong failed to admit that in 1996, when he was in the hospital room terminally ill with testicular cancer, he told doctors that he had used testosterone, human growth hormone, steroids, cortisone, and EPO. (Armchair physicians might be prompted to ask a question: is that not perhaps why he got cancer?) Betsy and her husband Frankie are among those who heard him make the admission.

All he could say is, “I don’t want to get into that.” Thereby rendering this whole Oprah thing as pointless.

*

In 90-minutes of Oprahfied yakking, Lance Armstrong did not do the three things folks were expecting him to do:

- Cry

- Admit to co-founding and co-administrating the greatest private doping conspiracy in sports history

- Apologize unequivocally

It’s interesting that he’s said that what he did was nowhere near as bad as the East German doping program of the 70s and 80s, in which a bunch of ersatz Dr. Mengeles experimented with abortion doping and other outré techniques in order to ensure that their Aryan proxies made it over the line first. That program was the result of a political system so twisted that it could only produce disposable athletes who faded away when they started losing, dying of tumours and exploding organs in their late twenties in shitty Marzahn-Hellersdorf co-operative apartments.

What, one wonders, does Lance Armstrong’s story tell us about our own social and political system—bamboozled as we are by Nike-branded winners with a tear-stained backstory? Dr. Michele Ferrari and the numerous other co-conspirators listed in the Reasoned Decision document, despite their protestations to the contrary, were in possession of no empirical data regarding the health effects of their doping programs. Ferrari famously said that EPO was no more dangerous than orange juice, which is a lie that may well one day be used against him when he’s forced to explain why so many of his one-time protégés are dropping dead. So in what way was Armstrong Inc. better than the East Germans? His “admission” certainly didn’t make that clear.

In this dark context, nothing that Armstrong says to Oprah matters. Because a TV special is the wrong forum for his confession. He needed to go before the USADA, the World Anti-Doping Agency and a phalanx of journalists microphones and come completely clean. It would have taken him all of five minutes, and then he could get on with the business of defending himself from the hundreds of lawsuits hurtling his way.

What we get instead is a bunch of mealy-mouth dissembling. Now, you can go ahead and dismiss Lance Armstrong and his latest escapade—he didn’t kill anyone (yet) and everyone was doing it! But like I said, Lance Armstrong explains everything. He describes exactly how corruption works—how it takes shape, how it poisons a social system, how it sickens everyone it touches, and how it is cocooned by ideological purity (in this case, a superbly branded cancer charity.) No one rode and doped with Armstrong is any less guilty of cheating than he is. But they are not guilty of creating the mechanism behind the cheating. And that mechanism what elevates him from a mere cheat to a mastermind, à la Moriarty, or Darth.

It is now clear that Armstrong will never understand that. He will never understand that by acting as the central player in a doping conspiracy—by promoting a sophisticated cheating ring, by raising the money for it, by strong-arming and slut-shaming those who stood in his way—he is, by definition, more guilty. He is the guiltiest. He is a bad, bad man.

Look how far he got. If he was any less arrogant and had not returned to competition in 2009, he might well have gotten away with it. So close. The only thing that allows me a measure of peace is people like Betsy Andreu and Jia Ping. Had I not met with Ping after reading Oprah’s wretched Tweet, I would have got the feeling I sometimes get—this cloud swallowing every last molecule of optimism and fellow feeling. This sense that the human project is damned—because all too often, the Lance Armstrong’s of the world end up doffing the spandex, donning a suit, and starting to stump. I have no doubt that Armstrong would have moved into politics. He had the will, and he had the backing. Like his sycophant quoted above inadvertently noted, he would have been brilliant at it.

“At a certain point,” Jia Ping said to me, as we were wrapping up, “all of this cheating, all of the corruption—the people who do it, they cease being human. When enough people stop being human, you have what we have in China. It really is quite terrible.”

What’s also terrible is that there is still another hour of Oprah/Lance to go. Who knows, there might be tears. Even monsters cry, on occasion.

*

Pre-order Richard Poplak’s forthcoming Hazlitt Originals e-book on Lance Armstrong from these retailers:

Amazon Kindle (US / Canada / UK / International)