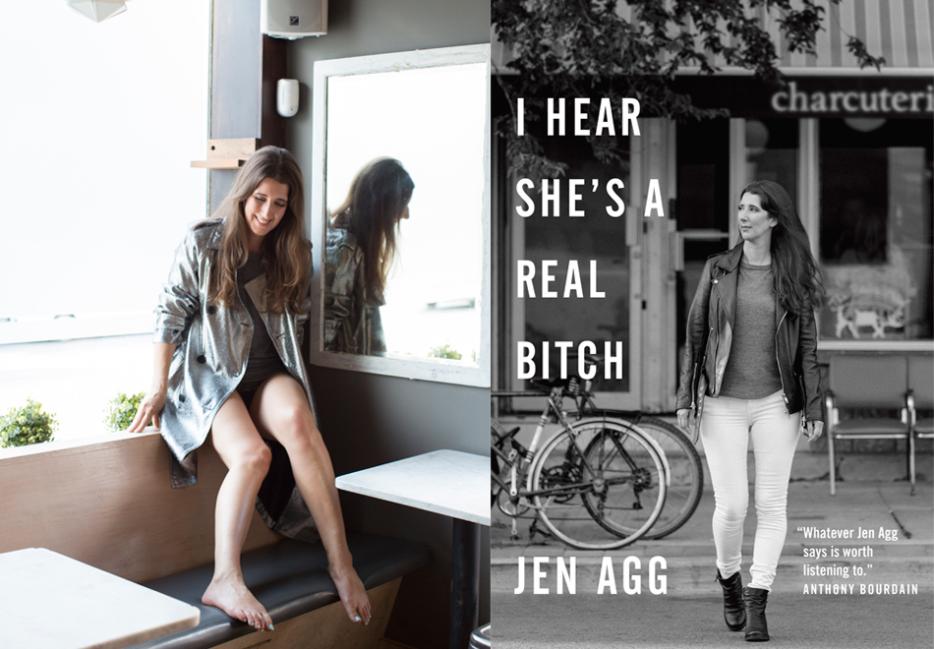

About a week before I interviewed Jen Agg, author of the newly released memoir I Hear She’s a Real Bitch (Doubleday Canada), I spoke about my own work at a Ryerson University journalism class. All of the students were women, and they all wanted to know how I navigated writing about my own life. Wasn’t I afraid of saying too much? Wasn’t I afraid of angering the people I wrote about? Wasn’t I afraid to talk about feminism? Wasn’t I just afraid?

The word rattled in a way that’s truthful. I tried to be inspiring. I told them that nobody has a right to tell their stories but them. I said that the world would be better if more women shared their stories. I said, be vulnerable, but I also said be courageous—dissolve your fear like salt in water, throw your tears down the sink. The unsettling truth, though, is that it can be scary to turn your soft underbelly to the world, to show strangers your rage and fear and all the things you did wrong and right. The words freeing and cathartic and terrifying can shift unexpectedly, like one of those where-did-the-ball-go? carnival games with the cup. The truth is that it’s by turns delightful and awful to be a real bitch—even if you’ve reclaimed it, even if it’s tongue-and-cheek.

I wish I could have shown those women Agg’s book. I would have said, This is how you do it. Or maybe, I would have been more Agg-like: This is how you FUCKING do it!!! This is how you be yourself on the page. Be bold. Grow. Share your mistakes. Tell us how you got back up. Tell us how you soared. Be the hundred different things that make you the person you are and do not write just to be liked—your story is so much more important than that.

As a feminist and head of her own super-popular restaurant empire, Agg tells us what it’s like to dominate an uber male, often misogynistic industry. But as much as this is a story about stumbling and triumphing as a woman in the biz, it’s also a story about simply being a woman with opinions. (So, like, basically, just a woman.) In I Hear She’s A Real Bitch, Agg cuts through the crap and lets us see who she really is—and how she got there. I chatted with Agg in her new Toronto restaurant Grey Gardens about periods, the word “outspoken,” and what it means to defy others’ definitions of you and tell your own story.

Lauren McKeon: Over the years, you’ve had a lot of press coverage. It feels like a lot of people have tried to write your story for you and define who you are. How did it feel to be able to tell your own story and have control over it?

Jen Agg: I hadn’t thought about it in quite those terms, but I do think it was a big reason that I wanted to write the book. I was tired of being shoved into someone else’s narrative of who and what I am—usually based on them not knowing me at all, or based on a public perception that is hugely rooted in misogyny. So, yes, it felt good.

To me it seems that often when someone writes or talks about a woman, there’s this tendency to try and fit us into these neat little boxes. Sometimes it feels like we’re allowed to be this set number of things, and if you venture outside that—well, watch out.

That’s been my whole life. When people start to know who you are, they start to have ideas about you. Maybe one time you didn’t hire someone and then they tell seven of their friends what a bitch you are because you didn’t hire them—I’ve told stories like that in the book. Or maybe you just have the temerity to say what you think, which is not okay if you’re a woman. It’s really, really not. It’s hard to ignore that. I think the counter-argument people will make is, “Jen, it’s not that you’re a woman, but that you’re legitimately outspoken.” There’s a case to be made for that, but I don’t think I’m judged by the same standards that outspoken men are judged. Recently, I’ve had journalists call out misogyny in other articles written about me. It was heartening. Can you say heartening? It warmed my heart, but I think it’s also a sign of the times. I’ve had these feelings and this fight for my entire life, but it feels like our culture is finally starting to fucking catch up to it.

You used the word outspoken, and you also tackle it in your book. I wanted to touch on that word: outspoken. A lot of the time, when it’s applied to women, it’s a slight, but when it’s applied to men it’s more like oh, he’s so courageous in his opinions. How gendered has that word become? What are people really saying when they call you outspoken?

When people call women “outspoken,” they’re calling us rabble-rousers. Shit-disturbers. I’m literally quoting myself from the book, which is so fucking embarrassing. But that’s what they mean. They don’t mean that with men. I understand the point to balance. I do say more than what a lot of men say. And I do say what I think. But I do also firmly believe it’s a gendered term. It’s just rooted in the idea of a woman’s place, and a woman’s place is to sit down, shut up, cheerlead for the men—to make sandwiches, but not run kitchens.

It’s so strange to me. The word outspoken should be a good word.

Shouldn’t it? Yes!

Like you’re standing up, you’re speaking out.

Maybe we can Take Back the Night on it.

Right? The word should be so good. Instead, it’s just become so gendered. The idea of women being loud isn’t something we’ve yet hurdled over.

I’m going to pause you right there. It’s not even loud. This is actually a thing I’m starting to take issue with. I’m not loud. I’m calm and nuanced and able to think through my thoughts well. Just because I’m using all caps for emphasis—with tongue usually firmly planted in cheek—it doesn’t mean I’m literally screaming.

I see the point. It’s okay to be loud. I like that idea too. At the same time, I’m actually not a screaming harpy. I’m not being extremely nuanced right now, because it’s so early in the day. I mean, it’s not really—but for conversations like these. But here’s what it is though: It’s not being loud; it’s just saying words. It’s just saying words. And that’s what’s so offensive to me. It’s not loud. It’s just speaking. It’s just speaking words. And when you start to identify “loudness” in terms of women who are just speaking words, it does us a disservice.

There’s a moment in the book where you’re talking about some of the threats you get on Twitter and you say something like, “I have to laugh it off because what’s the other option?” Can you expand more on that?

I make a little joke somewhere where I’m like: “I’m not getting rape threats. What’s wrong? You don’t want to rape this?” It’s an extremely inappropriate joke and I realize that, but I do try to twist it into something funny. That’s because it’s unimaginable to me that someone is so driven into a frenzy of rage by the words that I’m saying that they want to murder me, or they want me to get raped, or they want my tits to be cut off and fed to me, or whatever egregious thing it is they’re saying. You really do have to laugh.

I read them to my husband sometimes and he can’t handle it. He gets more upset than I do. It isn’t even that I’m not upset by it, but for now it’s easier and better to not take it seriously. Not that I don’t think it’s serious. I think it’s serious and gross and really beyond the pale. I do think all of those things. But if I were to entertain the idea that any of these men actually wanted to rape me, I don’t think I would be able to sleep at night.

Right. Either you let it infiltrate your own life—and it can—or you laugh. In a way it is ridiculous. It’s gross and wrong and all those things, sure. But at the same time, it’s also ridiculous that these people on the Internet are in such a frenzy.

Because I said words. I do think it’s ridiculous and I try to ignore it. I also have this really remarkable ability—and I do think it’s remarkable and I don’t know if it’s just how much wine I drink—but I’m able to move past and forget things really easily. That’s not to say I don’t hold a grudge. I hold a grudge excellently. Although I also accept reasonable and legitimate apologies like a champ. But I can just forget shit. Someone can say something extremely cruel and cutting on the Internet or in a comments section somewhere and I’ll read it and say, “Oh that’s fucking rude,” but I’m able to file it away. It’s like water off a duck’s back. It’s very effective in controlling how I feel every day.

Given all the stuff people write about you, did you ever think about how the book would be received when you were writing it?

No, I really wrote it for me. I wrote it as catharsis. I wrote it as telling my story from my perspective. I know me better than most anyone else. Maybe not better than my husband, but I like to think I do. I just wanted to get the words on the page. It was remarkably easy to tell my own story. I just thought about plowing through each chapter and eventually I started to see it come together like a Tetris game. I also wrote the book while I was building two restaurants and living in two provinces. I wasn’t thinking about much other than fucking finishing it.

I never get bogged down by what other people think, though. Of course, every once in a while I can get my feelings hurt. I’m not made of stone. I think people sometimes think if you’re a strong woman you can take on the world. And it’s like, “Yeah, basically I can get right back up, but I fucking have feelings.”

Whenever I read women’s memoirs, the unsuccessful ones to me are the ones where women feel they either have to be so self-deprecating (I’m not that good)or, on the other hand, like they have to be superwomen (struggles do not exist). What I loved about yours was that there are the moments of confidence, which are deserved and awesome, and then there are the moments of vulnerability where you pause and show your feelings. It’s often really hard for women to do that because we face so many pressures. Was it a conscious choice for you, and how did you push yourself?

That’s a great question. No, it’s not conscious. This is the thing that I think maybe people don’t understand about me. I’ve encountered some journalists who seem to believe that somehow everything on my Twitter feed is calculated. Nothing could be further from the truth. Five minutes ago, you said something and I wanted to tweet it and I resisted because I know we have limited time. That is how I tweet. And that is how my book works as well. This is, as much as possible, how I see myself and it’s an honest depiction of who I am. That’s what we’re searching for—who we are. Who are we? How do we exist in the world? And I really, really try to show all sides of how my personality developed, how I am in the world—all those things. That included things that were difficult to tell and it included admitting weakness at times in my life, which wasn’t easy. I also think that it’s insulation from other people putting those things on you. If I hadn’t told certain stories, I would be opening myself up to somebody saying, “Well, what about this?” I didn’t want that. I would rather be like, “This is everything; take it or leave it.”

That touches on another thing I wanted to ask you.

I’m just segueing for you.

We’re like in sync, but not the band. That would be less cool. ANYWAYS. Returning to the idea of “This is who I am.” You mentioned catharsis earlier, which is interesting because while I was reading it, I kept thinking, “This must be cathartic for her—to tell her own story.” I think inevitably when women write their own stories someone will always say, “Well did you ask so-and-so if you could write about them?”

It’s not their story.

Right. It strikes me as expecting women to ask permission to tell their own stories. It really irritates me. You were very open about sharing stories about your interactions and relationships with those in your life, good and bad. Did you face that when you were writing this—or did you ever think, “I don’t know if I should mention this person?”

Only one time. With my husband. With everyone else it was like, “This is fair game.” But with my husband Roland, I wrote about some very private things in our marriage. When I wrote that chapter, I felt it was important for all the reasons I just discussed: it’s my story and it was a turning point in our marriage. So, I called Roland. He likes when I read my work to him. What is more beautiful than your wife reading you a story? I was kind of crying as I read it to him, because some of it’s really emotional. He just listened to it. And I was like, “Honey, is it okay?” It was more like, “Are you going to be okay with this?” This is very private. And he said the best thing ever. He told me, “Honey, this is your story to tell, and it is not for me to tell you whether it’s okay or not.” But, yes, he was okay with it. It was such a relief.

Speaking of Roland, I have to admit I laughed that I got to the part where I got to the redacted part [in the advanced review copy] about his nude drawing of you. This handwritten note from you fell out when I turned to the page where Roland's drawing will appear in the book when it goes on sale, and it read "REDACTED! Nude. Of me. LOL—you'll have to buy the book" and I thought, this is the best. Women get criticized for so many things, for telling their own stories—

For being naked?

Yes, for having bodies and saying, “This is my body, not yours.” How did that decision to share that come about—and even just to write about the body in the way that you do. How did writing that feel?

It felt great. All of the art in the book is by women—except for the art by Roland. We weren’t going to do any photographs so it didn’t make any sense for anyone other than Roland to draw me. This is the true story of what happened. I was reading in bed. I didn’t have pants on because I’m in my house. Of course I didn’t have pants on! He comes in the room, and he’s like “Oh, honey.” He gets his iPad and he’s like, “I need a picture of your pussy.” So he made me pose. And he told me he was going to do a nude of me for the book. At first, I thought “Ohhhkay, that’s an interesting choice.” But then I realized that’s actually fucking cool. We talked about it and decided it’s art. As Roland said, “ Art is beautiful, your body is beautiful—so why not?” I’m sure I’ll get some negative, ugly backlash from shitty men about it, but I don’t care. It’s a beautiful drawing.

Did it tie into your decision to talk about sex? They seem linked: the ownership of our bodies, and also the ownership of the statement, “Yeah, women have sex and we like it.” It’s complicated and complex and fun for us too.

Absolutely. I didn’t think I could write a memoir of my life and not include my sex life. That would feel very incomplete. It’s a very important part of my life. The story I tell about losing my virginity—that is really what happened, of course. My friends really made me feel like it was seedy and obscene and I should be embarrassed. At the time, I was so young that I thought maybe they were right, and it stayed with me. Then one day, I realized they’re not fucking right. This is ridiculous. Men can fall dick first into any hole around and it’s fine. The idea that women’s virginity is a gift that we’re saving to give to the right person is fucking gross. I’ve always hated it.

In a way, it goes back to telling our own stories. I feel like women have to keep telling their stories and more and more. We have such an incomplete understanding of women and their lives.

It feels to me sometimes that women are not in touch with their own bodies because we’re just trained not to be. Whereas, I’m really sensitive to what’s happening. I know which ovary is operating which month and I think talking about periods is fine. We’re taught to be ashamed of this stuff at such a young age. Like: hide your tampon when you go to the washroom. I think most women probably still do that as adults. And part of my fighting instinct is to really loudly announce stuff like, “I’m going to go change my tampon.” Well, actually it’s actually a Diva Cup, obviously.

So you also joke about white girl feminism a few times in the book.

I am a white girl, technically speaking.

It’s a huge conversation in feminism right now: How do we move past white girl feminism? How did your feminism evolve as you were writing the book?

All the hard questions, huh? I don’t know if it evolved while I was writing. I’ve always tried to be intersectional. It’s obvious to me that I’m going to have an easier time fighting for feminism than a woman of colour will. And it’s always been obvious for me. I really do try to be an ally. It’s a complicated subject, but I do understand the concepts of how to amplify someone else’s voice: move aside and let people speak; when you’re on Twitter, do retweets and don’t just quote tweets; and so on. I really do try to do that. I understand the privilege I have, obviously. I understand my middle class privilege. I understand my white woman privilege. And I thought it was important to acknowledge that in the book, to not pretend to be oblivious to it. The more people that talk about it, hopefully the more it will seep into the mainstream in a real way—it’s starting to.

Why do you think people are still so scared of feminism in general?

It’s the status quo. People like the oatmeal they’ve had every day. They don’t want a different bread, even if it’s way better. Even women like the status quo, and especially the middle class. I had this great moment recently. A woman came into Grey Gardens with her husband. And I almost started crying in front of her as she told me her story, which is trés embarrassing. She told me that when she first came across my Twitter feed, she dismissed me. Oh, she seems crazy. But then she started to really read my feed. And she decided a lot of what I was saying made sense. Eventually, she started speaking up at work. She was a smart woman, somewhere in her 40s and none of this ever occurred to her—probably because she’s had a semi-privileged life. Now she calls herself a feminist, she speaks up at work, she engages in feminist actions. And, she told me it was all because she started reading my Twitter feed. It was really powerful. It meant a lot. So I don’t care about the haters. If I can have one story like that a month, that’s enough.