Jesmyn Ward is one of the great writers of our time and when I dial her number, I am nervous. When she answers, I learn that she is trying to find her way out of a building after a radio interview on the campus of the University of New Orleans. There is no one around and she has been locked out. She enters a new unlocked door and finds herself locked in again. As I commiserate with her over this experience, my nervousness ratchets down. Ward is human—she, too, gets lost and has to find her way back. We decide that she should call me back after she finds her way.

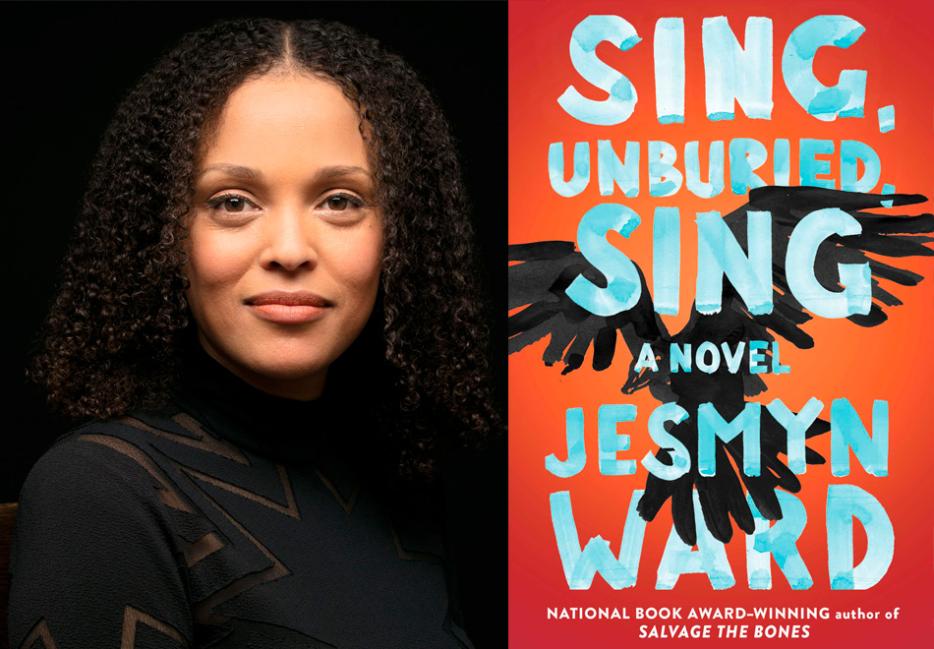

Ward is the author of three books—two novels and a memoir—and the editor of an essay collection. Her second novel, Salvage the Bones, is one I recommended to friends over and over for its storytelling and poetry-infused prose. I read Men We Reaped while in transit, thinking of loss and those taken too soon. Sing, Unburied, Sing (Simon & Schuster) is her latest, and just last night, won the National Book Award for fiction—her second time taking that honor (she previously won for Salvage the Bones in 2011). The novel simultaneously takes place over the span of both days and decades. At the center is a family: Jojo is a biracial boy, Leonie is his black mother, Kayla is his baby sister, and Pop and Mam are his grandparents. In the novel, Jojo and Kayla go along with Leonie and her friend to pick up their white father from prison. It is a story that deals with what it means to be a family, what it means to grieve, what it means when the past won’t let go. Once again, Jesmyn Ward has created a work that is stunning in its representation of humanity and of people who often don’t get the chance to be rendered as human.

Ward calls me back once she has made it outside. We talk about failing others because you have been failed, legacy, and the pressure of awards. We talk about more. Occasionally, I hear the wind.

Abigail Bereola: Jojo is a sweet thirteen-year-old boy trying to navigate what it means to learn to be a man. To him, manhood means confronting death without looking away and it means denying himself very human things, like touch. Where do you think Jojo picked up these constructions of manhood? How much of it do you think comes from him and how much is what is put on him by other people?

Jesmyn Ward: I think that a lot of it is put on him by other people. Most of the good he’s learned from Pop, about what it means to be a man, what it means to be a black man. This idea he has that men nurture—that men are caretakers—I think he gets that from Pop. This idea he has that you express your love for people by caring for them, by providing for them—I think he gets that from Pop. I think that the bad ideas he has about masculinity, I think a lot of those he’s getting from the outside world. His ideas about showing emotion, and there are ideas that he has about what it means to be a person of color and what it means to move about in the world as a person of color—I think his ideas about that, he’s definitely getting from the outside world. But I do have to say that I think that he’s a naturally sensitive person, and so I think that some of what he understands about what it means to be a man and nurture and be a caretaker, I think some of that is just because of who he is. Because he’s sensitive and because he’s so empathetic, you know?

Yeah. That’s interesting with thinking about how he does have this example of a nurturer who is right in his household, but he still feels like there are certain ways that you can nurture certain people while he kind of cuts the nurturing off with regard to himself.

Huh. Yeah. I feel like… in part, maybe he’s getting some of that from Pop, from his grandfather, but in some ways, it might be that the reason he believes that is because Leonie is still his mom. I think in some ways he might be modeling her, because she doesn’t practice self-care. She’s a really destructive person. So, I think some of that may be coming from her—from watching her and the ways that she moves through the world and interacts with the world, and at the same time that she’s failing them, she’s failing herself in certain ways. So, maybe some of that is coming from Leonie.

I think it would be easy to say that Leonie is a "bad" mother, but you wrote her in such a humanizing way that I think it’s also easy to say that she is a woman who is seeking love, but who doesn’t quite always know how to give it, especially to her children. She’s grieving her brother’s death, her boyfriend’s imprisonment, and aspects of her own life in some ways. Her kids offer something other than what she is, other than her pain and self-hate, but they are also emblematic of it. Her brother, Given, was failed in the way that he died and in what came after, but do you feel like Leonie was failed, too, as a person among those who were left behind? And now she fails others because she doesn't know how to process her own pain?

Oh, definitely. Definitely. That was the key for me, the key to understanding who she was and why she failed those around her. Why she neglects her children, why she is sometimes emotionally and physically abusive to them. Because she had been failed. Because she had been left to learn how to bear underneath this grief, how to carry that grief throughout her life. And she was left to struggle with that alone, in some ways. I mean, in the end, I think we all have to struggle with our grief alone, but she—I don’t know, I think that it was hard for her because maybe she didn’t have any models for how to do it. And it seems that her mother and her father were struggling with their grief and I think it was so difficult for them that they couldn’t see beyond their grief to help her through her grief. In a way, I think that that’s a really natural response because the grief of losing a child—I mean, I can’t imagine how awful that must be. But I know from experience, from my own mom talking about what it was like to lose her son, that it’s a special kind of hell. And so, I think that in some ways, Leonie was left alone to struggle with this thing and I think it’s the great wound of her life. She can’t see beyond it because she hasn’t begun to heal from it. Because she can’t live with it. She can’t confront it. She can’t sit with it. I just think that it complicates everything for her and I think that it makes her even more self-involved, even less able to care for others around her. To care for her parents or her children. To care for herself.

In Sing, Unburied, Sing, there are many elements of the supernatural, but they feel so intrinsic and intuitive to the world in the story. Some people have referred to the novel as magical realism. Do you agree with that characterization? And either way, do you see the novel as resting more on the side of magic or more on the side of realism?

I think it’s a combination of the two. I can’t deny that there are supernatural elements in the story. But I think that my understanding of the world that the characters live in is that the supernatural and the natural are inextricably bound to one another. One can’t exist without the other. So, I think it is magical realism.

I guess I think about it as delving into different aspects of black culture that aren’t always at the forefront, but are very real for the people who experience and practice it, if that makes sense.

Yeah, that totally makes sense. One of the reasons that I wanted to write about voodoo or write about hoodoo is because I feel like in the larger culture—in American culture—voodoo is something that has been maligned and I think that black spiritual traditions were important and are still important, for many, for our survival. I come from an area where a lot of people are Catholics—I was raised Catholic—but yet in voodoo, you have this example, especially in New Orleans, of elements of African spiritual traditions melding with Catholicism. I think that voodoo and hoodoo were a way for people of African descent to feel as if they had some sort of power or control in their lives, especially when in every other aspect of their lives, they were denied that. I think that those traditions are really important to understanding how we survived, how we exerted control, how we assumed some power, how we claimed some agency for ourselves throughout the hundreds of years that our ancestors were enslaved. So, I wanted to push back against that understanding of voodoo, of hoodoo, of that kind of black spiritual tradition, so that people are better aware of how it, again, helped us to thrive and how it helped us to fulfill some really deep-seated human needs that we had.

When reading this novel, I was so excited that Skeetah and Esch from Salvage the Bones made an appearance. Do you think of all your characters across novels as existing together in the same world?

Oh, yeah. The characters at the center of my first novel were a set of twins and those were the twins that Leonie is talking about. There’s a flashback when she’s thinking about Given and Given and Pop were working on his car trying to get it together and she says, “Oh, I wish so-and-so would walk down the street.” She’s talking about the twins from my first novel. In my head, they’re all existing at the same time, in the same place. In part, what I feel like I’m doing when I’m casting about for ideas for novels is that I’m trying to figure out who else lives there. I’m trying to find more people in that place so I can write about that.

I really love that.

Yeah?

Because that’s how life is, too! We all exist at the same time, even though we have our own stories. Do you see yourself as having an overarching project that you are working toward, that all of your books add to?

I think in the end that will be the result. But right now, I don’t have everything mapped out. I haven’t reached that point in my career where I’m thinking about legacy yet. I’ve met writers who are… I sat in on a lecture by John Edgar Wideman once and he was talking about legacy and he had sort of reached this point in his career where he was thinking about what had come before and thinking about the time that he had left, so he was trying to figure out what he would devote his time to and what his body of work would look like, but I’m not there yet. I haven’t begun approaching my projects like that yet.

For me, it’s really two different things that are happening concurrently. I am finding voices that speak to me. Characters that intrigue me and who I’m curious about and characters who want me to tell their story. For Salvage the Bones, that was Esch. For Men We Reaped, of course the most important character is my brother. For Sing, it was really Jojo. Jojo came to me first. So, I’m finding characters who want me to speak, but then at the same time, I’m also finding myself drawn to the same ideas. I’m obsessed with the same things. And so recently, I feel like one of the big ideas that I keep returning to and trying to figure out is I keep thinking about time and about history and about how the past bears on the present. And how it affects people in their everyday lives. I think that those two things are happening at the same time, that I’m drawn to characters but also these bigger ideas about time and history are circling in my head. But I’m sure maybe in five, ten years or so—I mean, I’m forty right now, so if I live to forty-five, or if I live to fifty, then I’m sure that I’ll reach this point. It seems like many writers reach this point where you began thinking about the time you have left and what you’ve done and you begin to plan your projects. But I’m not there yet.

By now, you are the recipient of one National Book Award, a finalist for another, and the recipient of a MacArthur Grant, among other accolades. Do you find that these achievements add a sense of pressure to the work that you’re doing?11This interview was conducted before Jesmyn won her second National Book Award.

Yes. Yes. Yes. I mean, I think that they add pressure for several different reasons. Because the weight of what you’ve already done and the subject matter that you’ve already written about, as a writer, you’re supposed to be thinking about audience. You’re wondering if people want more of what you’ve already written, so in some ways you feel pressured to write about certain things. And so there’s that pressure… At first, when I won the [National Book Award] for Salvage, I felt a sense of pressure because I thought, “What if this is it? What if this is the best that I’ll ever do?” And so, I think that also makes you feel a certain sense of pressure because you’re wondering if you’ve peaked as far as your work is concerned. Yes, these accolades definitely do exert a certain sense of pressure, but I don’t know. Whenever I get something—and I’ve told this story before—my NBA award from Salvage is at my mom’s house. The certificate I got, also at my mom’s house. Any time I get any sort of award that comes with a memento or something, I always give it to my mom because I feel like it’s easier for me if I don’t see them. Because then when I sit down in front of the computer to write, it helps me to forget—to sort of shrug off that pressure. Do you know what I’m saying? And to forget audience for a second! Because I think you have to. In order to really feel a sense of creative freedom and just write, you have to forget audience. I feel like audience is something that I allow myself to think about when I’m revising, but when I’m writing a rough draft? When I’m really creating something, then I feel like it’s necessary to forget audience because, I don’t know, I feel like a constant awareness of audience can make you choke sometimes. It can make you choke. So, I try to forget.

Who do you write for?

Speaking of audience! Many different people. On one hand, I think I could say I write for fifteen-year-old me. I write for kids who don’t see themselves in literature and who want to see themselves in literature. I write for those kids. Then I also write for present me. I write for twenty-year-old me. Aspiring writers. I write for black women. I feel like I write for my family. I write for my community. I write for my region. But then I’m also aware of the fact that I write for people who are nothing like me. And I’ve been aware of that fact from the very beginning, because I remember thinking when I was younger, when I just started out, that I wanted to write about the kind of people that are in my family and about the kind of people that I grew up with so that people who aren’t like me—so that some of the awful kids that I went to school with who were white and also racist—would read about people like me and would feel for people like me. I don’t solely write from that impulse anymore, but I am aware that I do write for people who are nothing like me. And I’ve met a lot of people who come from very different backgrounds, very different places. After Salvage the Bones was published, I went to New Zealand for a book festival. And I remember meeting a lot of readers there and they had just experienced the Christchurch earthquake and I remember meeting people and those people saying, “I love this book so much because it spoke to me, especially after the earthquakes.” And so here they were, approaching the book and loving it and feeling empathy for the characters because they, too, had lived through natural disasters. So, I don’t know. I’m aware that I’m writing for people, like I said, people like me and people like the people that I know and love, but I am also aware of the fact that I’m writing for everybody else, too.