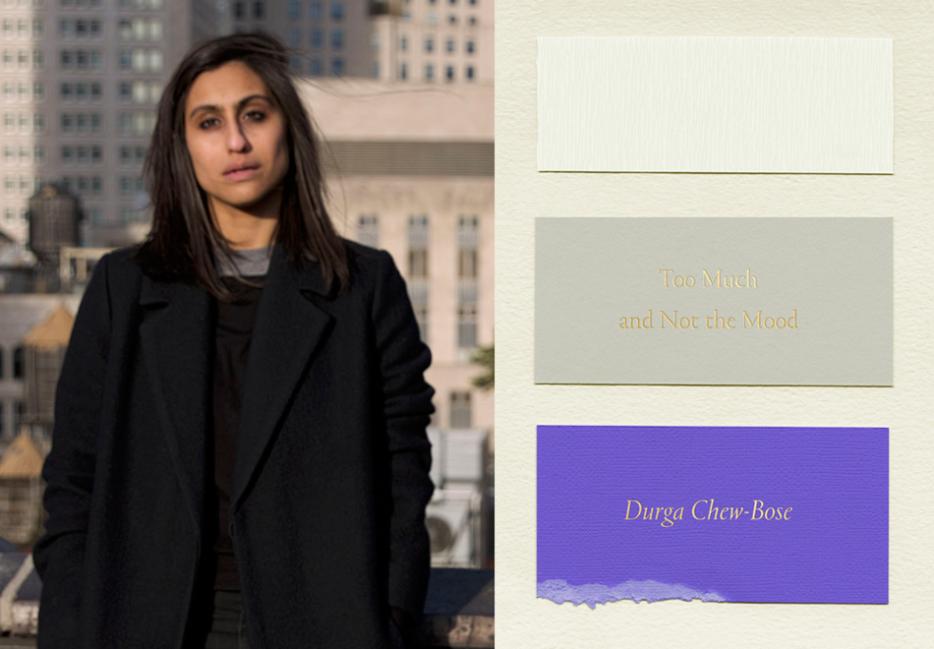

Like many great things, I'm pretty sure Durga Chew-Bose’s work first became known to me through Tumblr. Her account stood out to me because of the connections her mind makes, evident through the curation of her thoughts (usually screenshots of tweets), reading that she’s found necessary to add to her page, and her favorite visuals.

Despite the likelihood that it has only been a few years at most, it’s hard for me to remember a time when I haven’t known of her. What intrigues me about Chew-Bose's work is that it feels, not like an invitation into her mind, but like you're already there, perched, awaiting her next thought. Chew-Bose’s words are deliberate and often inspire rumination.

Her new book of fourteen essays, Too Much and Not the Mood (Macmillan), is spiraling and full of challenges. In much of the text, she negotiates being the daughter of parents who are originally from India, but growing up as a first-generation Canadian in Montreal—being “from here but also… from there too.” She weaves in her friends, her brother, her favorite artists, writers, moments. These are the things that make up the fabric of her being, and so they must necessarily make up the fabric of her stories. Too Much and Not the Mood reads like a coming-of-age tale, if the focus is on the tale and not the age. It considers who she was as a child in Montreal, as a young adult living in New York City, and who she is still becoming.

Named to Brooklyn Magazine’s list of “30 Under 30” in 2015, when asked where she saw herself in ten years, she said, “In ten years I hope to be better at everything without even noticing that that’s true.” We spoke on the phone on a cloudy New York morning in March, both in Brooklyn at least for the moment.

Abigail Bereola: Your Tumblr often reads to me as a virtual art gallery of sorts—there’s a form of tight curatorial effort at work. Do you consider your Tumblr as more of a project than a blog? Is it for you first, or do you have a target audience?

Durga Chew-Bose: I don’t really consider it to be anything, to be honest. Probably the least of which a blog, because I don’t really write on it often. Occasionally, I’ll write, but it’s so rare. I kind of use it as more depositary. I’ll read something and something will strike me and I guess I have some far away idea that everything I see and consume and am enthusiastic about will eventually find its way into my work… or solve some problem in something I’m working on. And so, I think it’s more a compulsion than anything else. It’s probably the only aspect of my life in which I could claim being even half a hoarder. I’m usually getting rid of things constantly—I don’t like owning a lot of stuff. The only thing I buy a lot of is probably books, but Tumblr is kind of—in some ways—very opposite to how I consume and live my life, because it seems like an abundance or an over-abundance of things that might not necessarily be related but that just strike me. And then I just feel the need to put them somewhere. I just use it like—I don’t even know—like a safe deposit box, or something. Sometimes I’ll go through the archives.

I do find it helpful, though, in that a lot of it is—even if it’s as small as an interview with a writer or director, sometimes the way artists whose work I admire speak about their work reinvigorates me and I think I keep my Tumblr for that reason too, because it’s a good place to turn to when you’re feeling directionless… I definitely feel like I also keep it because it’s the only place that I don’t have to present myself with much cohesion or context. So actually, to answer part of your question, I don’t have an audience in mind. I barely even consider the fact that other people are seeing it. Ever. Oops.

In your essay “Heart Museum,” you write about being born first generation as being born in dispute—that you must not only survive, but thrive in the home where you were born, but also continue to think of your parent’s home as your first, in some ways. My dad was also born and reared in a country different from where I was, and I have often, from a young age, felt “in dispute,” but for me, this manifests as a feeling of not fully belonging to either place. Have you felt this way? Does it mean something different to you?

Sometimes I wonder if my personal relationship to what it means to be first generation is also so dependent on the fact that I haven’t been to Kolkata as much as maybe some children. Some children visit where their parents are from once a year at least, and they have a whole parade of cousins and second-cousins and people that are called cousins even if they aren’t technically cousins, you know? And I definitely don’t have that relationship to being first generation because I think that in the case of those families, there’s much more of an emotional tether. Their sense of family is very global in some ways. Well—global is such a cheesy word, isn’t it? I just mean their sense of family and what it means to be part of a family is expansive. And in some ways, I feel like my family is a very small unit and now we’re all in Canada. And because my parents have now been living in Montreal for so long, I feel like that negotiation between who I am and who they are and where they’re from and where I’m from has lost some of those distinct lines in some ways. This is all I know and this is the only way that they know me. I don’t feel as torn, so much as I do feel occasionally—I don’t know what the word for it is, but sometimes out of nowhere, I’ll suddenly remember—it might be as simple as, you know, I was just home in Montreal and there was a huge snow storm. And it’ll be something as small as watching my father shovel snow. And it’s looking very hard on his body right now. And me considering, “Oh yeah, he’s not from here. But he is now, at this point, because he’s been here for so long. Why is he shoveling snow?”

It’s a very simple moment, but in some ways, that sometimes will shake me into realizing that some extensive travel and abandoning of one’s original life has occurred for him… It comes to me in these rare moments. I consider the family tree in a very physical way… I think that’s more how I contend with the fact that there are questions, not necessarily that I’m looking for answers for, but they’re definitely part of how I navigate the world.

You mention, throughout the text, in various iterations, that the stories of parents do not belong to their children. And it’s interesting—their stories can feel like yours because as a child, you’re of your parents, even if you are not them specifically. A really striking moment that I thought illustrated this was in “Part of a Greater Pattern,” where you refer to your parents’ separation as your first heartbreak. And I think there’s something really interesting in the idea of an experience that is secondary to you becoming primary, even though that experience likely felt primary to you. Do you have any thoughts on this?

Well it’s funny, because when you’re writing, everything is in retrospect. So, I wouldn’t have, as a child, even recognized it as heartbreak. I probably would have clocked it more as confusion and pain and questions and sadness… But in terms of my parents’ stories not belonging to me, I think part of why I wanted to express that is because I think it’s also a question of respecting their individual lives that are running alongside their children’s. I think there’s this idea, especially when there is second-generation/first-generation stuff happening in a family, or the dynamic is definitely demarcated by a family immigrating to another country and raising their children in an entirely different world—I think there’s a sense, and the word that comes up a lot is that parents are “providing” for their kids, creating this world where they can thrive. I think part of my relationship to my parents is that as much as I feel incredibly close to them and sometimes even psychically close to them, I understand that they have an entirely complex and separate experience of what it is to be a person. And I think my relationship to them is a very equal mix of curiosity, but without prying. Curiosity that is less trying to get the scoop and more that I love the stories, but I also respect their privacy. I feel like I only really mentioned it once, but maybe I did mention it more than once.

I think specifically you mentioned it once, but it kind of felt a weaving theme in some ways, like you talk about not asking certain things.

It might also be that I haven’t yet asked it. I think there’s always a time or there’s a natural way that information is divulged, or stories are shared and you can’t force them, especially with parents. My mother sometimes says she thinks I’m the member of the family who is going to be really invested in continuing the family’s stories—for obvious reasons that I’m a writer, but maybe for less obvious ones that I have this very irritating quality of asking a lot of questions, and they’re not often elaborate. They’re very detailed. My mother was telling me this story about growing up on Elliott Road in Kolkata, and I’ll want to know what shoes she was wearing that day. Or I’ll want to know where they were going or the name of the shopkeeper or the name of the tailor, because for some reason, I tend to have a harder time imagining. Or maybe it’s not even that. Maybe it’s that I love the cinematic quality of being exposed to what otherwise might seem like inconsequential details, or something. In that way, I think that when my parents are telling me anything, I push for all those little details, but in terms of the deeper emotional stuff or choices that they made, even, I really believe that those are theirs to share and tell me when they feel the time is right. Or never tell me.

You describe a restlessness associated with being first generation, of the movement instilled in DNA. And I think you are describing this more psychically than physically, but I wonder, have you personally often moved around? Do you feel that you know what it is to settle down?

That’s actually really funny that you’re asking me that right now because I was just texting with a friend, telling him how I’m feeling a little bit out of sorts because I’m living in sublets right now and I’m in other people’s spaces and I’m essentially not fully unpacking my suitcases. And his reaction was like, “No, that’s exciting! That means you’re not tied down.” I thought it was funny and I was laughing because in some ways—I feel like this is such a ridiculous thing to say and I should probably not say it—but it felt so male: tied down. I always just associate it with how men talk about relationships or something. And I was like, “No, I desperately want a space of my own right now.” But I think it’s, if anything, teaching me that it’s important to have to learn how to improvise your interior life a little bit more. I’m definitely someone who likes to nest, so this has definitely been an adventure in terms of learning how to live with all my stuff in a series of small pouches and bags, and carrying my toothbrush and my backpack regularly and always having some books with me to read if I crash at a friend’s place. Always having all my chargers. I just feel like I’m a mobile office unit at this point. So, that actual physical restlessness doesn’t necessarily suit with my temperament or how I would like to live. But it’s temporary, right? And with anything that’s temporary, it’s all you have to remind yourself to get over that moment of complete panic or feeling like you’re a failure or something.

But no, I haven’t been someone who has had a very nomadic life or anything. In fact, I’m definitely the kind of person who, even when I know I’m going to be somewhere for a short period of time, I try to find little ways to make it a home. It’s been harder this time because I find that between teaching and the book and going home to see my family and meet my niece and stuff, I’m just letting things happen to me as opposed to organizing my life around some pattern that makes sense, but I think you’re right, the restlessness that I was speaking of is more psychic and also a question of heritable belongings. Honestly, sometimes it’s just that you can feel that your parents are completely foreign people because when you’re reconciling with something you’re going through in adolescence, their adolescence was in a completely different world, and so, you almost—instead of trying to connect—had decided young that you weren’t going to be able to, which was probably naïve and silly, stubborn teenage behavior, but I think that’s part of it, too. Your understanding early that there’s going to be a lot that’s lost in translation and either you have to do the work to make those connections or just make these empirical decisions, like, “Nah, we’re just not going to meet when it comes to these topics.” And that can make you really restless, I think.

That’s really interesting, and I think, actually, what you said about trying to make everywhere you go, for no matter how short a period, kind of like a little home—I wonder if that kind of stems from similar things.

I don’t know if I’d put that much deep thought into why I try to have my comforts around me. I think it’s just I’m someone who is a bit terrified of unraveling. But I think I just appreciate when things are in arm’s reach. I have to say, it’s been kind of tricky not having all my books. Like even if I’m just writing or there’s a sentence I’m trying to retrieve and I wish I just had all my books to walk into my study and find that one copy of whatever and be like, “Oh yeah, I didn’t make that sentence up. That definitely happened.” That’s been a bit hard, to not have that access… But sometimes I wonder if it’s just a question, too, of convincing myself of having a life. And it’s hard for me to do that if I’m not surrounded by my intentions. I think having a space of my own or living in my own apartment, there’s this clarity in every corner or every wall you look at, or surface. It’s your own and you placed that object there. And sometimes that’s enough for me to get through the day, is to know that that glass is there because I used it. Sometimes that’s enough to clear up with myself that I’m alive and I did something at 8am and now it’s 8pm and I’ve lived a day in this space.

There are a lot of really lovely moments throughout this work, but one of the sections that kept drawing me back was in “D As In” where you write about delighting in anonymity. I have felt similarly in a lot of cases—there’s more of a desire to fade into the background, at least in a personal sense. You frame this as having been “born accommodating,” which I think is a lovely turn of phrase, but quite complex for the people born this way. For you, does having been born accommodating infringe on the work of writing?

Yeah, for sure. I think there have been times when I’ve tried to write and accommodate some anonymous universal audience of shadows that have no distinguishing qualities and the writing has, for that exact reason, been awful. I try to fight that whenever I write now and I’m trying to be, more than ever, very specific and write to a few people in mind and keep those people in mind when I lose track of what it is I’m doing or why it is I’m doing it. But I think it’s important to distinguish between accommodating and pleasing. I definitely don’t write to please people…

But I think the accommodating is that I want to make myself as clear as possible to make myself as accessible as possible. And in order to do that, I feel like that requires some accommodation. It’s very nerve-wracking for somebody to look at you but not see you and I sometimes wonder if in my own writing, I’m trying to accommodate or express myself in a way that people can see me, which I guess kind of goes against what I wrote or what you asked about, in terms of wanting to fade into the background, but I think it’s also worth mentioning that that essay was written almost three years ago now and things have changed. I think I’m a different person in a lot of ways and I think I’m trying more actively to not seek invisibility as much as I might have in the past…

Early on, in “Heart Museum,” while discussing smallness in relation to the happenings of the Earth, you ask, “Because doesn’t smallness prime us to eventually take up space?” With regard to the idea of accommodation in the sense of being pleasing, as opposed to the larger sense, have you found that to be true?

Yeah. And when I mean smallness, again, it’s not necessarily physical smallness or making myself completely into a speck. I think smallness in that respect is also patience, or listening, or watching, or perceiving and quietly observing, or collecting over time. Appreciating how patterns form naturally instead of trying to be a part of the pattern. I think a general reluctance has actually helped me find my footing a little more than had I just confidently walked into rooms or confidently assumed that my opinion or point of view was immediately valid. God, I would be a completely different person. And maybe it’s completely wrong to suggest that it’s good to feel invalid young, but it definitely made my relationship to writing one of a lot of process and thinking as opposed to immediately writing. So, I think in that way, the way that I know how to take up space—the only way I know how—is with my writing…

I do know it can probably seem a bit confusing—I’m saying, “Don’t take up space!” And you know, people love these banner statements telling women, “Take up as much space!” and I guess I agree with the sentiment. I’m still not 100% on board. Because taking up space also requires a certain amount of security that you can make those mistakes and still have a second opportunity. And I’ve never felt like that’s necessarily an option for me. I don’t really think it has anything to do with identity. I think it could just be personality type, and I think that’s a really important thing to make clear. I might just be some kind of lapsing perfectionist at this point and I’m understanding that I can’t control as much as I used to want to and a lot of the smallness is totally symptomatic of wanting control. So, I don’t necessarily think it’s completely married to questions of identity and who’s the loudest in the room and who’s not and whose voices are encouraged and whose aren’t. Although of course that plays a determining part, I think it’s also just a question of my personality. My personality is often one of needing to be careful about how I present myself.

I agree with the idea of smallness in both ways not necessarily always being a bad thing. I do think that the things that are often seen as negatives often lend themselves to more empathy or things like that. In “Since Living Alone,” you refer to yourself as “a child that never quite reveled in the traditions of childhood.” Could you talk about that more? Do you ever feel like you missed out, or that you need to make up for lost youth?

I don’t think I think I need to make up for lost youth or that I missed out. I was just a very tense kid. I was not cool or calm or confident or funny or coming home with stains all over my clothes. I was tightly wound, tense. I was living in a home where I was very concerned about my parents and their marriage, even though it was none of my business. And they were the greatest parents and created an amazing home for my brother and I, but I was still playing adult. I think I was trying to understand adult emotions and adult pain, when obviously I did not have any tools or equipment to do that. I think I also just was in my head a lot. And I think maybe that is a quality that is very childlike, but I don’t think I had that reckless abandon that some children have or pure unbridled joy. I talk about this in the book, but it’s something I so wish I could hear. I just want to know what my laugh sounded like as a kid. Because I have no idea what I sounded like when I completely let go and I’m just really curious.

There are many moments in the essays where you say how old you are at the moment of writing. What is the importance in proclaiming your age?

I think that maybe sometimes, especially with the essay on my name, having my friend Sarah in that moment in the bar question that man for asking something that has been asked to me my whole life, I think it’s important to mention how old I was because it had taken my whole life to meet a friend who was just so bored by this person’s really, really, really uninteresting interrogation of who I am—the least interesting part of me, you know? It had taken that many years for that to happen and for a friend to do that, but also for me to even realize how illegitimate that question was. So, in some ways, I probably mention my age because I do want to note that these aren’t experiences that have changed me when I was 14, these are experiences that changed me when I was well out of college and when I thought I knew everything there was to know about myself or when I assumed that maybe I had built up enough reinforcement and I felt like a reasonable, legitimate person, but no, yet again, there was a moment where I’m kind of struck by how narrow-minded people are… Maybe I have mixed feelings about the age thing. Part of the time, I wish I stayed away from how bold an age can look on the page, and other times, I think it’s important because it really underlines how there are certain experiences I’ve had my whole life that I never thought to question because I just thought it was how things would always be.

In “Since Living Alone,” you mention how while living in New York, you “rarely [cashed] in on the proximity of people.” I definitely related to that—New York is the biggest city I’ve lived in, with the most friends who live in the same place, and yet I rarely see many of them. It often feels like everyone is so hyper-focused on living their own experience and trying to make it here, that it can be hard to see something or someone else. Do you feel that it’s something particularly true in New York, or have you had similar experiences elsewhere?

Let me think about that for a second, mainly because I lived my entire twenties in New York and I think that’s that time in our life where being social is an expectation. Obviously every writer has said it better than I will ever say it. There was this essay in Granta Magazine one issue and I think the issue was about travel or family. I feel sometimes like I have all these sentences on the tip of my tongue that I’ve read, that have been so important to me and now, I can barely remember what they were…

But there’s an essay in it, and he has this line about what a friend in New York is, and it was like, “A friend in New York in fact was defined as someone you never needed to see, who would never get angry at you for ignoring him.” I feel like that’s a huge part of it because sometimes I think a huge part of living in New York is literally what it takes to get outside—everything you need to get done before. And I also think that it’s so tiring here often and being social can be really tiring and that you can love your friends deeply, and it’s honestly the ones who love you back just as deeply where they understand that it’s not a big deal if you don’t see them. The love is there when you’re thinking about them and the support is there when it’s really needed, but that electricity to always be where everyone else is can really deteriorate you, so I think that’s also why people don’t end up seeing each other a lot.

I remembered, it was Edmund White. I remember it totally because it was in this issue of Granta—it was like my favorite issue because—I think it was in 2014 or 2015, but it had all my favorite writers. You know when you get an issue of a magazine and you’re just like, “This is a jackpot because every contributor is my favorite writer and I’m going to keep this like it’s a Bible…”

The proximity of friends thing in that essay was also because at that time when I wrote it, I was living in Crown Heights and a lot of my friends were a block or two blocks away, and it would kind of shock me how Friday would turn into Sunday evening and I hadn’t even considered that I could just walk over to my friend’s and sit on her floor, or walk over to my friend’s and make lasagna. Instead, I just kind of devolved into someone who forgets to turn on the lamps at night. I think that’s also part of it, but maybe I should just blame our laptops or something. If I didn’t have a laptop, I’d probably go outside more. I don’t know…

I think Too Much and Not the Mood is a work of self, but also of family and friendship. There is something about the way you describe your female friends, as if, more so than any lover, they are the loves of your life. What significance do your friends have to you?

I was telling my friend Sarah a year or a couple years ago how my whole life changed when I met her. But it wasn’t, oh, my whole life changed and I forgot about my life before her. You know how there’s sometimes a piece of art—you see a movie or read a book and you can’t remember what your life was like before you read that book because that book solidified so much that just felt kind of jiggly in your head and now it’s solid and concrete? That’s not what I mean. I think I just mean that for the first time in my life, I met someone who everything I’ve known and felt but didn’t have words for or couldn’t funnel into some kind of meaning found that space, because I feel like even if our shorthand wasn’t quick to develop, we really believed that the other person was very special. And so, my whole way of thinking and writing and being around people has changed since I met her.

I think a lot of my friends have that impact on me, too, where simply watching them talk on the phone with their parents or watching them work through many drafts of a piece of work and watching them arrive late to dinner and need to unwind and the care that they put into listening to their friends. All that stuff has just taught me how to be with other people and sometimes I feel like I have a hard time being with other people, but my friends make me feel like it’s okay—whatever I come with, there’s room for that. I wouldn’t say they’re like the loves of my life because I don’t even know what that means necessarily, but I do think that they are what encourages me to constantly be a thinking, caring, loving person who wants to provide for them. But I don’t even know what I would provide, honestly. You just want them to be as incredible as you know they are and as they know you are.

It’s a bit ridiculous, honestly, how much my friends have helped me. I was telling my friend Collier as she visited me in Montreal—we were just talking and I don’t even know what we were talking about. You know when you’re with a friend and suddenly, you’re both just so happy that the other person exists, but there’s also a sadness in that and I can’t really explain why. I just felt this crazy honor, like this person whose work I admire and whose brain and whose sense of humor and whose energy—oh my God, her energy—it’s a wealth of energy. And I was like, “This person has chosen to come to Montreal and visit me and spend time with my family’s dog and go for walks. This person, of all the people in the world, wants to know me.” And that’s how I feel about my friends, in some ways. I just want to know everything about them, and in knowing everything about them, I end up learning everything about the world. So in some ways, I think that’s partly why I feel so indebted to them, because they’re so generous in sharing with me what they’re experiencing and what they love and what they see, and they’re so generous at also sharing the less bright parts, like the pain and the loneliness… Sorry. I might have gotten a little cheesy.

No, that was really beautiful. I’m going to double-down on the loves of your life thing, because that’s what it sounds like. I don’t know. I guess different people have different ideas of love and what it means and what it can be, but I kind of tend to think of it in the form of expansiveness and people who are really rooting for the best for each other and who feel like they make each other better, and I feel like you kind of described that.

Yeah, I think that that’s actually a huge part of it, too. A lot of the women in my life, I just see them as the most brilliant people I will ever meet. And I know how frustrating it can be to want to be clear about something that’s exciting to you or make that project that you so desperately want to make, but you have seven other things you have to do before, and I think part of our friendships is that we are also reminding each other of those original excitements… I always return to this idea that one of the greatest things you can offer your friends, especially in a city like New York where ambition seems to actually make life feel impossible in this kind of oxymoronic way, it’s so important to have friends who when you’re saying, “But that person’s doing better than I could ever do” or “I can’t believe that person did that,” it’s really important to have a friend who can be like, “No, but you are doing it.” You need to hold up a mirror to your friend and be like, “This is you and you are making it happen,” and a lot of the women in my life, that’s what they’ve done, and I’m so grateful.

Who do you write for?

I think I write more to people than for them. Because I often just will write, even if it’s a single sentence, to a specific person. I think I also write for that part of me that couldn’t express what I can express now. And I think I also write to that part of every exchange I have where so much goes unsaid. Because one of the beautiful things about writing is you can spend all the time you need to say it like you want to say it, even though I’m sure you always want to go back and edit. That care that goes into it? I think I write for that, too. I write for the care. For the time that I get to do it properly, the way that I want to do it… I felt in writing the book, I couldn’t have done it without the women in my life who I’m constantly talking to or texting angrily about whatever happened that day. Those people were who I wrote to because they are who I talk to regularly. I can’t write to people I don’t talk to regularly because that’s not connecting to me at all. That’s just kind of like tossing my ideas out into some imaginary space and hoping that some of it sticks, but if I write to the people I’m in at least regular contact with, then I can hope that some of what I was saying will make sense, honestly. I just don’t want to not make sense.

I think it’s possible, too, that I don’t write for anyone because there’s something about the word “for” that seems really presumptuous to me. But if I write to people that I know, that I regularly talk to, then all that presumption can maybe evaporate a little bit. There’s no separate me. The me that’s writing my book is not separate from the me that’s having dinner with a friend, so to make sure that I maintain that, I was always very, very clear that I was writing to specific people in my life. That was the only way to adhere to that tone, I guess.