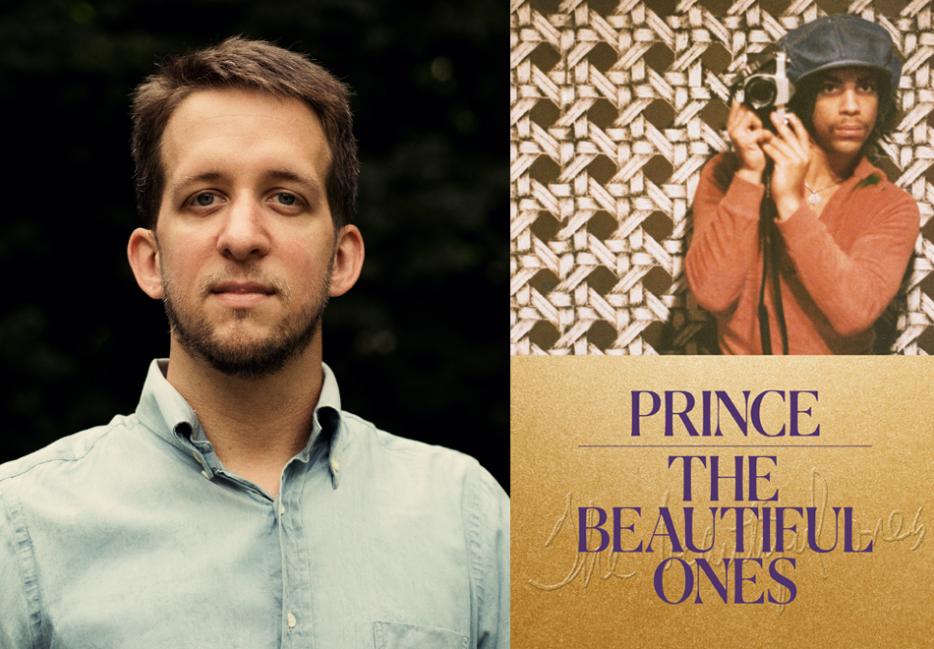

There’s a series of selfies in the middle of The Beautiful Ones (Spiegel & Grau), a book that began as Prince’s memoir, that has more than once brought me to tears. Nineteen at the time, Prince takes photos of himself in a red pullover and denim micro cutoff shorts, with matching red leggings layered underneath them. His expression suggests someone who is testing out how they want to be seen.

“I took this picture of the heater and I, in the bathroom window. mirror. (soRRy) (Sorry!)” reads the back of one. They present a slightly unsure version of Prince, unlike anything I’ve ever read or seen about him, I first think, until the last shot. He gazes through the camera with one eye, at the mirror—his audience—with the other, his left hip hiked up and right hand fanned out, fingers adjusting the lens. A fake hand creeps out of the crotch of his shorts. Hilarious, tender, an unexpected gut punch. Prince had always known who he was, even when he was searching.

Dan Piepenbring was supposed to help the American music icon tell a story that included these versions of himself by collaborating with him on his memoir. A 29-year-old online editor at The Paris Review who had never written a book at the time, being chosen for the job seemed extremely unlikely—and extremely like something Prince, a longtime hero of Piepenbring’s, would do. But only three months and barely thirty pages into their work together, Prince died from an accidental fentanyl overdose, revealing a largely concealed opioid addiction and cutting the project short.

This means that The Beautiful Ones could not be a memoir, and should not be read as one. There is Piepenbring’s story of meeting and working with Prince, and such stories are a genre of Prince lit unto themselves. There are the pages Prince himself wrote, which reveal that many of the stories he told about himself through his art weren’t fiction. And then there is the archive: reproductions of photographs, drawings, original song lyrics, even equipment rental receipts found in Paisley Park after Prince’s death.

I spoke to Piepenbring about how one takes those three threads and turns them into a book.

Chantal Braganza: This book exists through two almost-didn’ts: the sheer improbability of being chosen to co-write Prince’s story, and his death, after he’d written only 28 pages of material. How do you press on after a start like that?

Dan Piepenbring: It was tough, and not the natural thing to assume would happen. After he died, and I had his pages in my possession, I thought the world needed to see them. I was biased on that count, having had this amazing experience with him. And of course, a lot of skepticism greeted that. Because it’s not an unfinished memoir; it’s a barely-started memoir. And I think for almost anyone that would be disqualifying.

But because it was Prince, and because he was so shrouded in mystery, and because he had done the writing himself—and it was in a quiet, deliberately domestic way so revealing of him—I think that there was a much greater chance of us to carry on.

Prince commanded complete control over his output. This book is transparent about how it came to be, but what do you imagine Prince would have thought about the decision to continue without his input?

I can’t put any words in his mouth and I wouldn’t want to. I know that those pages he wrote, he was very proud of. He read them to friends, and he would talk about my conversations with him to others who were close to him at that time. So, I felt comfortable putting them out. Especially because so much of what we talked about involving his parents did come from his desire to correct the record about them, and to correct this mystery-ing of Purple Rain as autobiography.

I hope he’d be happy with the book. I’d never want to come outright and declare that he’d be happy with it—that’d be wrong. For all I know there’d be parts of it he didn’t want out. Parts of it he’d be dismayed by. There’s no saying.

The rest of the book is derived from material you were able to review from his estate. What kind of an archivist was Prince?

One of the reasons my editor and publisher and I thought there would likely not be a book is that we expected him to have kept very little. He was someone that, for the majority of his life, would say that he had no interest in exploring his past. He would always say that his favourite album was the one that was about to come out. We were shocked to find not only that he had kept some reminders of his past, but that he seems to have been a very conscious documentarian of his own life.

But then, when you think about The Vault, this fabled storage area for all of his music, maybe it wasn’t so surprising. I feel like, with Prince, there was always a cancelling-out. Anything you were surprised by you could step back from and look at another way, and find made sense.

What’s it like to edit his writing?

It was great, because he’s a great writer! You can really see, like in the economy of his lyrics, a songwriter’s talent for elision. It really came through in his prose. And best of all, his sense of humour was in such abundance there. And I think that sense of mischief he ascribed to his mother is everywhere in his prose.

After he died, I didn’t want to change anything. To do that without having him to sign off on changes would be wrong. But he was receptive to the few criticisms I offered. They boiled down to one thing: I felt he would do well to slow down and expand some of these themes that he had very carefully dredged up from his past. They felt raw to me. Even though he had given them the comic treatment I could tell there was more he remembered that hadn’t gotten to the page yet, and if he had gone back to that well he would be able to draw up so much more.

People talk about a writer’s voice. Not so much about an editor’s. What was yours in the making of this book?

I wanted to tell the story as plainly and as openly as I could, because I felt that if I did anything less people would wonder what had given me the authority to do this book. In addition to serving as a final profile of Prince, the introduction had to make a case for the book existing at all and project the final vision of the unfinished book that would exist in parallel with the thing you’re actually holding.

I knew I wanted to avoid any sort of obituary-style critical writing. That I wanted to avoid the feel of something summative or interpretive. That I just wanted the events to speak for themselves.

Did you ever think much about the idea of meeting one’s heroes before doing this?

I’ve been approached by movie producers about turning our introduction into a film. Which, I think, would be terrible. I don’t want to do that. The one I always reach for in comparison is The End of the Tour.

In college, around the same time I was listening to a lot of Prince, I was also reading a lot of David Foster Wallace. Which is probably the most expectable thing that someone like me can say, but it’s true. But other than that, I hadn’t really given it much thought, because of the sheer unlikeliness of it. It really is a fantasy construct. Usually, when you see it on TV or movies, it’s this imagined thing. It was dramatized once in Prince’s case. He had gone on this episode of New Girl with Zooey Deschanel. And he was responsible, if memory serves, for resolving this conflict between two lovers and getting them to declare their love for one another.

Yes! I’ve seen the episode…a few times.

Yes! It’s great. He’s said that music is healing, and this is the perfect example of that. My experience was much less scripted and doesn’t have the five-act frame of a sitcom episode, it really wasn’t all that different, in terms of the sheer surprise of it and the fact that it worked out very well. Everyone says that the line about meeting your heroes is that you shouldn’t do it. That they’re going to disappoint you. And it wasn’t true in my case.

It could have been. He was known as a fickle man and he may have decided he didn’t want to do the book, or that he didn’t want to do it with me. There’s a number of things that could have gone wrong. But even had it never come to fruition, his presence really was inspiring. I still struggle, through all the interviews I’ve had to do for this book, with how to articulate it. But it was so ineffable in a way. He was so devoted to making you feel at ease and giving you a sense of accomplishment that even someone with confidence would not have necessarily had. It seemed like he was using his stature for the best possible good.