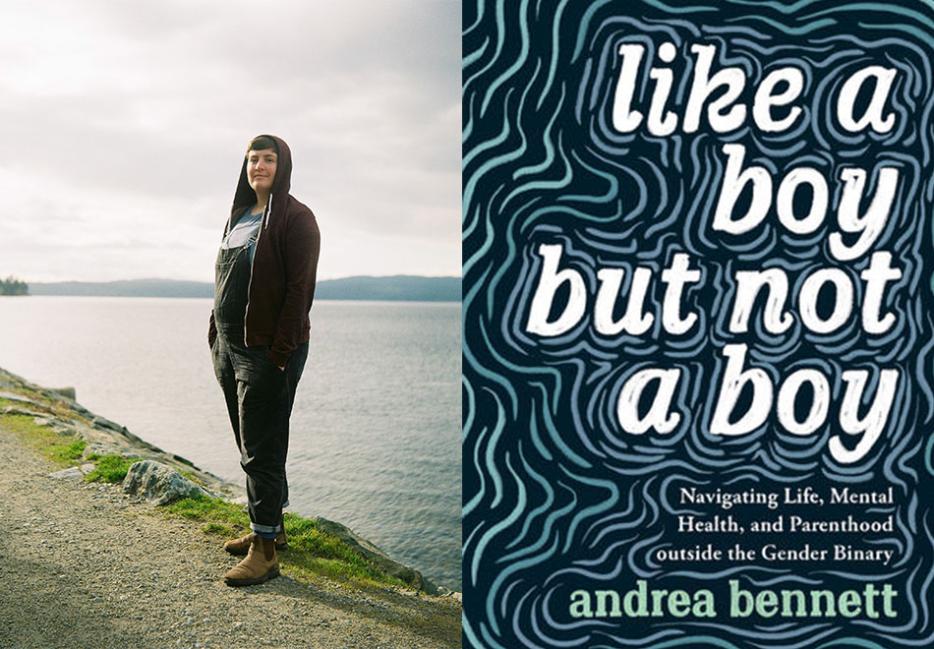

Despite knowing andrea bennett for years, I didn’t realize how perfectly many of our anxieties overlapped until I read their latest book, Like a Boy but Not a Boy (Arsenal Pulp Press). The memoir addresses, with frankness and humour, topics that I, and probably many of you, find at least somewhat uncomfortable to think about: our social class, our faith, our bodies, our mental health, and our mortality. And yet, there is also plenty of joy throughout as bennett navigates their gender, becomes a parent, and finds beauty in what often feels like a burning world.

Once, when we were both living in Quebec, bennett and I took a summer weekend road trip with their spouse and a mutual friend. We stopped at Chutes-de-la-Chaudière, a set of waterfalls just outside of Quebec City, to stretch our legs. Strung across the gorge in front of the falls is a narrow, 23-metre-high suspension bridge. As we approached it, the others strode easily across, but bennett and I hesitated. Neither of us had to explain to the other what was deeply unappealing about having nothing but an elbow-high fence and some cables separating us from plummeting into the Ottawa River. By the time the other half of our party was making their way across the bridge, we realized we’d have to join them. I can’t remember what bennett and I talked about as we crossed, but I do remember that, although my cortisol was spiking, the mist from the water, the sun on my skin, the sound of the falls were all so enjoyable that I calmed down enough to feel as though all four of us would likely make it across alive. Reading Like a Boy but Not a Boy feels something like crossing that bridge.

I recently caught up with bennett over video call to speak about the book, queer parenting, the quest for immortality, and, for some reason, Kim Kardashian.

Ziya Jones: So, tell me, what was it like to release an essay collection in a period when everything is [gesturing frantically] like this?

andrea bennett: I’ve been lucky so far. Arsenal, my publisher, has been really supportive. I couldn't ask for more in a year like this. It kind of sucks to launch a book in a pandemic year. But everything sucks in a pandemic year.

There are some nice things about online meetings. You can kind of just Zoom in from anywhere. But as a reader, I miss the kind of feedback you get from being in a room. The body language from readers, the vibe of the room. I don’t know how to explain it, exactly, but it exists. Rooms have vibes!

There's definitely something about, like, showing up to a venue after work. And you see a bunch of creaky chairs, or it smells kind of like beer, or if you’re like me then you get there late and there aren't enough seats so you sort of shuffle regretfully to the back of the room and find something to lean on. God, I miss leaning uncomfortably in public.

Yeah, and actually, some literary festivals are slightly fancier than my normal life. So, I would be lying to you if I said that I hadn't been looking forward to being flown places to stay in hotels and eat free cheese. There is an aspect of my personality that is very luxury-oriented. So, I am bummed about missing that. But it’s okay. You know that GIF of Kim Kardashian where she’s crying over losing her earring in the ocean and her sister's like, “There's people who are dying?” It's a little bit like that.

Have you done any readings in sweatpants yet?

I’ve mostly been wearing overalls. They’re sort of like a suit of armour. The same way some people wear makeup to help get them into the right headspace, I strap into my overalls. Honestly, I would like to put forward overalls as the official clothing of the non-binary. Non-binary can mean a lot of things, but I think about 90 per cent of us have a fairly large attachment to overalls.

I think that’s a fair assessment. Speaking of existing outside the binary, do you want to talk a bit about the title of the book?

So, I'm like a boy, but not a boy. It was originally the title of an essay of mine that first appeared in Swelling with Pride, an anthology that Sara Graefe put together for Caitlin Press. The stories centre around queer conception and adoption and things of that nature.

The title comes from walking in Montreal one afternoon while I was pregnant—and I think probably wearing overalls. A woman looked at me and said, in French, to the person she was walking with, “You think they’re boys but then they’re not boys.” It was this derisive aside. I don’t know if it was a kind of rude power move in that she thought I couldn’t understand French. But anyways, that rude lady gave me the title for the book basically.

It also describes fairly well my early conceptions of my own gender. Once people started talking more about non-binary genders when I was a little bit older, then things clicked into place and I found a nice home for myself there. But, growing up, I did kind of just feel like a boy, but not quite making it over that line.

I can definitely relate to that early childhood experience. And then you spend the next two decades or so swinging back and forth between binaries until you’re like, “Wait . . .”

“Ohhhhh, I don’t have to stick to one!”

Totally. A lot of the more universal themes in your memoir feel very timely right now, like death and mortality and the anxiety that comes along with living in a body that will eventually have to contend with both those things. Does it feel surreal to be releasing this into the world at a time where suddenly everyone is thinking about these concepts more than usual?

As someone who is obsessed with fearing death, it’s been an . . . overwhelming year. Perhaps that fear of mortality has also come to the surface for people who don’t usually experience it daily.

The funniest or at least most ironic thing is that the book ends on this note of optimism. It’s like, I’ve gone through some shit but I’m in a place where I feel more stable and I feel grateful for where I am. But I don't know what to do with all of the anxiety that I have that propelled me here. In the closing essay I essentially ask, “How do I relax and enjoy my life now that I’m not in survival mode?” Now everyone is in survival mode and we’re basically sacrificing people so capitalism can keep churning. We have so few places to collectively direct our anger other than when, like, Kim Kardashian rents a private island or something. So, yes, it’s weird to have this particular text arrive during a pandemic year, when life is more unsettled than usual for every single person.

I included a number of interstitial essays about other people throughout the memoir, and the same is true for them. A few of the subjects felt they’d reached a point of stability with their partners, with their lives. And, unrelated to COVID-19, some of their situations have since changed as well.

I guess that’s just a built-in risk of writing non-fiction. We don’t normally get a change as dramatic as a global pandemic, but life always continues after we wrap up the narrative arc.

Narratively, essays do need a beginning, middle, and end. As a writer and editor, I understand that. You have to give the reader a sense of conclusion. But that’s difficult with essays, especially if you are—like I did—using them as a space of exploration. It’s hard to feel settled about things. I rarely feel settled about things!

There’s this popular koan that I see pop up every once in a while that basically says, “The finality of life is what gives it its flavour.” But I don’t think that way at all! I’ve talked about experiencing anxiety but I also often feel depressed. And yet, I would still choose to keep waking up again and again. I guess there’s some hope in that?

It’s interesting that you say that now, at a cultural moment where embracing finality has become part of the zeitgeist. At least online, there’s this semi-ironic move towards framing death as the ultimate out from a world that keeps spiraling into increasingly dire territory. Every fifth meme is like, “lmao I want to die.” Contrastingly, one of your essays concludes with you saying about yourself and your loved ones, “Even if I could quiet the part of my brain that imagines worst-case scenarios . . . I would still, impossibly, want us all to live forever.” Why do you feel that way?

I mean, it’s probably kind of selfish. Like, “Here’s my ark, climb aboard! You’re stuck here now!” I think it's partially that I'm afraid of dying. I don't want things to end. I don't want my consciousness to evaporate. That could be like an ego thing, although Freud also talks about the death drive. It could also just be that I like being here, even though it sucks sometimes. And I would like to keep being here. The thought of my life being extinguished, or the thought of someone else's life being extinguished, is just too much for me. Every time I read about how human beings contend with death and dying, none of it rings true for me. I’d love to live several lifetimes. I just feel like the world is an inexhaustible well of cool stuff—there’s always something to appreciate. Yet, life moves through matter and my life breath is taking up a certain amount of matter. So, I don’t get to live forever. But I want to!

You write candidly not just about yourself, but about other people in your life. I remember you saying at one point that you felt some anxiety about how other people would react to being portrayed in your work. You come from a journalism background. As journalists reporting on strangers, we have this veneer of “objectivity” to fall back on. Plus, we won’t necessarily cross paths with sources after our stories are published. But when we’re writing about people we know, it gets messier. How do you navigate that?

Something that I had written about my mom years earlier pushed our already strained relationship to the point of estrangement. But I’m quite close with the paternal side of the family. There are moments in the book where I'm navigating gender-related stuff with them, concepts that, to them, were pretty new. My dad and I explicitly talked about the essays in advance and he gave me the green light to write about the complexities of that early navigation, even when they were tricky or difficult.

It's hard when you have loving relationships with people that have complexities, because you don't want to hurt those people by writing about the times they behaved less than perfectly. But in loving relationships there’s still conflict; there’s still misunderstanding. With queer people there are also often cultural differences between you and your family of origin. You come out again and again; you explain the same concepts again and again. It’s going to be frustrating sometimes. I think it’s important to share that. And I think my family is okay with what I wrote? I hope so? Maybe not . . . but if they aren’t, we can talk about it!!

You recently formally changed your pronouns (welcome!). Did the process of writing and releasing the book have any impact on your own relationship to your gender?

Yes, in the sense that I gave myself permission to claim non-binary identity. Which will seem so silly to some people and will make so much sense for other people. In my first book, Canoodlers, I was still figuring myself out gender-wise. I was testing things but had no clue what I was doing. By the time I wrote this book I knew what I wanted, but I just had a lot of fear around it. If you read the comments section of any piece about trans people, there's so much hate [and] vitriol. Growing up, I presented as more masculine of centre and I got called all sorts of homophobic slurs, had stuff thrown at me. So that fear was really real.

As a society we have this idea of coming out requiring a certain amount of certainty. But I would encourage people to just . . . give it a try! I hope that we open up more space for exploration, in particular for youth. For some people, you come out once and, you know, dust off your hands and that's that. For other people, it’s a process of becoming over the course of their lives. Their gender is fluid and allows more space for exploration. I think the option of space would alleviate a lot of the stress for some of us who are more neurotic.

Like, I had this anxiety that other trans people wouldn’t see me as “trans enough.” I know now that was more of an internalized fear. The vast majority of trans people are welcoming. They understand that your interior feeling of gender can be different than your exterior expression. For the longest time, we've seen non-binary identity represented by androgynous, assigned-female-at-birth bodies. But, of course, there are assigned-male-at-birth non-binary people who may or may not present feminine. And there are some of us who are bestowed Kim Kardashian-type bodies and don’t want them.

Okay, this is the third time you bring up Kim Kardashian in this interview . . .

Oh no.

Why . . . What’s with you and Kim?

I mean, God only knows. I do find her, and the relationship our culture has with her, sort of fascinating. Her body is a body she has crafted, and it’s one onto which we culturally project a lot of baggage. The baggage of desire and desirability, but also this thing of her body being just at the edge of what is desirable or acceptable. If and when she gains weight (while pregnant, for example), that desirability tips into being “monstrous.” And all of that is complicated by her racial position—a white woman repackaging beauty trends or bodily traits that have historically been associated with women of colour, mostly Black women. Taking those things and repackaging them and then all of a sudden, they’re broadly culturally appealing and she makes gazillions of dollars.

Mostly, I find it strange that bodies can have eras.

You write a lot about bodies in this book. Your own body, other people’s, the concept of embodiment. How do you approach writing about something that’s a site of discomfort?

I like when people write about things that they feel uncertain about or unsettled about or uncomfortable about. So, I pushed myself to do that. Also, like, I live here. So, I have to make my peace with it. And I have to discern what I should work on feeling comfortable with as is and what would be productive to change.

I was also writing through the experience of pregnancy as a non-binary person because I think it’s good to have a plurality of experiences out there. Some people who are trans or non-binary and get pregnant will find it a dysphoric experience, others will not. I found the experience fascinating. It was weird to see how people interacted with my pregnant body. The actual experience of basically being a vessel for another human was also really weird. I don’t know if some 28-year-old will pick up my book and read about this and be like, “Oh, this helps.” But I hope it’s helpful to someone.

You mentioned that the book features a number of interstitial essays about other people. What made you decide to include them in a book about your own life?

In a way I wanted the collection to be a slice of older queer millennial life. To just document a particular type of coming of age. Plus, I love interviewing people and having permission to ask people nosy questions about their lives.

When I was thinking about my own coming-of-age story, I was thinking about what it meant to have this desire to leave a small town, to escape so I could be myself. And I think that that's a fairly common narrative when we think about queer coming-of-age and small-town type stories. I was also wondering to what extent that narrative was true or untrue for others. Structurally, it’s a little bit weird, but it felt right to me. And as a poet, I give myself a lot of license to just fuck around and do whatever I want structurally as long as it holds together. The essays came about as a blend of journalistic impulse and poetic license.

Money and class also run as a through line. Are you the kind of person who is comfortable talking about money?

I probably talk about money too much. It was such an obsession of the early parts of my life because I started living on my own at 17, without any parental support, and I was so poor at first and it sucked. These days I think about money in terms of, like, labour and organizing more than I think about it in terms of financial markets and stuff, which, honestly, I feel should be abolished.

As workers, we need to be able to discuss money more freely so that we can have a better understanding of what we’re worth and what we’re owed. All that to say: if any writers, especially freelancers, want to talk about rates and salaries and advances, I’m happy to discuss these things in DMs.

But please no one ask me for financial advice. I have no idea what a mutual fund is.