On August 15, 1947, when India achieved independence from British Colonial rule, a series of divisions occurred. The most famous of these was Partition: the division of India and Pakistan, of Hindus and Muslims, of former friends and neighbours, of new lives from the old.

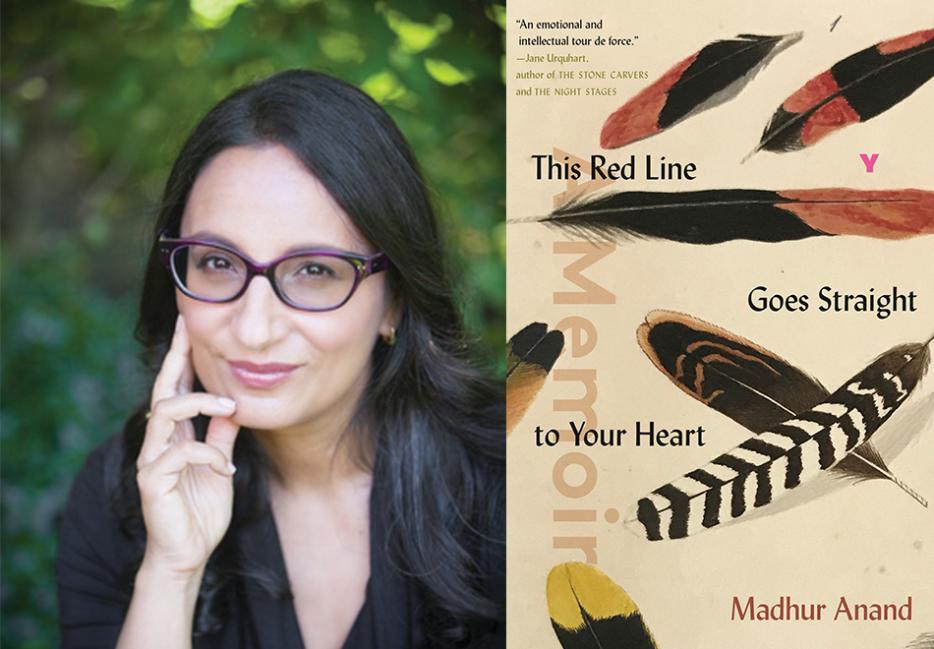

Depending on how you read it, Madhur Anand’s This Red Line Goes Straight to Your Heart (Strange Light) opens on Partition, alternating chapters to tell the stories of two strangers, future spouses, forced to leave their childhood homes, later emigrating to Canada in the hopes of starting a family. There, they must experience harsh Ontario winters, culture shock, language barriers, and nostalgia for a home that doesn’t quite exist anymore.

Midway through, the book hits a partition of its own. Stop, flip it over, and you have the memoir of Madhur Anand, daughter of the narrators of the book’s first half. A professor of ecology and sustainability at the University of Guelph, Anand is trained to look for patterns in the physical world around her, turning to poetry, science, and the theories of both to explain her present and her family’s past. This Red Line is a book about divisions, between generations, languages, geographies, and academic disciplines—divisions that are almost never neatly symmetrical, despite our intentions to read symmetry into them.

I call Madhur Anand at her home in Guelph from my family’s home in Ottawa, where we’ve both learned to adapt to the new realities of working from home. We’re interrupted a few times during the conversation, she by her children and I by my brother’s dog.

Anna Fitzpatrick: There's one portion you have in your half of the memoir, you're reading Allan Hume's The Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds, and you describe it as being outdated but you're reading it for the purpose of finding poems in it. Can you speak to that act of looking for poetry in other forms?

Madhur Anand: Basically, I'm newer to creative writing in a sense, to this whole thing of art. Having discovered that I'm an artist is, I don't know. I don't know when that point happens in a person's mind. Certainly, after publishing one book of poetry, I knew that I was going to continue doing it. The problem of course is you don't know how you're going to keep doing it. One can reach and fail and reach and fail, and certainly that happened before my first book as well. It’s an ongoing process. So you look anywhere, honestly. As you can probably tell from my book, I look everywhere for poetry. In the end, it's potentially present everywhere. You gotta keep looking. You gotta keep your eye on things. Everything in life, not everything is going to realize its full potential, including the poetry.

I came across that text almost by accident, while looking for something on the internet. I honestly don't remember initially what I was looking for. I can't always remember the order of things. You know how there are those print on demand services, and they reprint really old texts for you? They all have the same generic cover. All to say that the cover intrigued me at first, because it's a textbook looking cover. Several months later I realized it was the generic looking cover they used for all the old reprints regardless of the subject matter. I judged the book by the cover, but it got me to the book.

So, the book itself, I don't know if I described it, but it's a really esoteric text. It is a 19th century description of birds but not birds. There are no bird descriptions; only descriptions of nests and eggs. To me, the idea of a scientific treatise focusing solely on descriptions of eggs and nests and not the birds was just intriguing. I thought, Oh god, if that's not all the metaphor potential I could ever want from my next poetry book, I don't know what is. Not to mention that they're Indian birds, which, I don't know, and generally I feel like people in the West don't know about, because there's tons of scientific work that's very much Western hemisphere focused. US and Europe. But also, tons and tons of literary treatments of birds is also Western focused, robins and swallows and whatever. So I thought, OK, in addition to that metaphor, eggs and nests, there was going to be a lot of language and learning of these other species. They would be literally exotic to me and the readers. Anyway, I started to read it, and when you go into the text, it's like reading the Bible, if you've ever attempted to do that, which I have in my life. As a post-doc, I once just said, "Hey, I'm going to read this from start to finish and see what it's like." Because you hear so much about the Bible. I'm not religious at all, of any type, but I was like, let me just see what this actual text is, the original text. And once I started reading it, it was clear that no poems were coming. And then I sort of just got into the litany of it. The repetition, the pattern, the practice of it. Every day I just read a few pages religiously of this book, and I started to read it, and ultimately I did write some poems, and I do have poems.

You mentioned that it was hard to figure out a point where it was hard to call yourself an artist. Were there clearer milestones to calling yourself a scientist?

Those are such good questions that I toy with a lot. I always keep flipping in terms of what I think about that. On one hand, I hate the professionalization of either of those terms. They're not really professions per se. They can be, but to me they're both ways of being in the world, and ways of knowing the world. They're different. They can overlap, but they can also be complementary. I haven't quite figured it all out yet, of how they both figure into my life.

I feel that one can and should always go through the world thinking that you're artistically or scientifically inclined, and if you want to call yourself that, go for it, if you wish others to call you that, ask them to. I don't feel any problem with any of that. On the other hand, because I am a practicing scientist in the sense of, I have a PhD, I have been a professor, I’ve been doing research for twenty years now, and I know what it means to actually go through the scientific method towards scientific progress, and everything around it. I do feel there's a rigour and training and experience and ethic and community and all those things required to really call yourself a scientist.

I think the difference maybe comes to what it is you're trying to achieve with these labels. There's an area of expertise that one develops as a scientist. I am a theoretical ecologist, but I am not a virologist, for example. I think there is validity to those types of labels and there's an ethic of making sure that you are speaking from a place of knowledge and experience. On the artistic side, I think the same thing probably holds true, but I think one of the differences between science and art, and I could be wrong about this and certainly I don't think that artists think this, but I think it's the case in society that there's an expectation. Society in general doesn't feel like there's as much at stake with what artists do. I feel that maybe people don't care as much about that. But artists themselves, as you probably know, care very much. I think they're often questioning what it is to be an artist. Probably it is because of that problem of society not knowing what is at stake. And also not knowing for yourself what's at stake. One always has to question that with art. With science it's a little bit easier to know.

So when did it happen for me? I didn't feel it or think it, but if you look back on my actual practice and how I treated the appearance of art in my life—I wrote my first poem in the final year of writing my PhD thesis—and it was at that moment that I think that I became an artist, not because what I was writing was good, not because I was conscious of it, but because of how I engaged with poetry after that point. I took it seriously. I continued to work on it, and I continued to question it, and I continued to do it. I increasingly accumulated ambition for that art like we all do. I wanted to publish, I wanted to share it, I wanted it to be good. In hindsight, I would say it was that very moment only because of how I responded to it. That's it. Of course, as time went on and my first book came out, every little thing that happened after that reinforces it. You can always totally lose your way as an artist, which is I think harder to do as a scientist. In some ways I think because of that there is so much more at stake to remain an artist. Because you could lose it completely. Because it is mysterious, ultimately, how art is made.

You have a quote by Feynman that it's hard to get the history right when you are trying to explain something. Going into it, knowing it is a memoir, I still read your book like a novel with the amount of attention to detail, and shifting of perspectives. In your half of the book, you admit the gaps of knowledge in your own history, but with your parents the text seems more sure of itself, even though you're writing through the barrier of someone else's memories. How did you go about researching their stories and getting that voice down?

I'm glad you highlight the gaps and the questions, and yet I think generally speaking I was actually very reluctant to actually write any story from the first person of myself at all. I don't think I fully understand myself, right? I'm still only in midlife. My intent was not to write memoir. The function of my side was to give the reader some insight into who is the narrator of my parents' stories. Not who is Madhur Anand, you know? I'm not quite ready to write my full story. There are incredibly large pieces of my life missing on that side. Huge things. When I think back to the little stories that I included, I'm like, "How is it possible that the two most jerkiest guys are the stories that I write about." But I realized they had a function, and it wasn't really about them. It was about a time and a place. It's all to say that yes, there's a gap in memories and questioning and a lot of my side is still unwritten because it's not really about me, and I would like to pursue those perhaps one day, who knows. But there are major gaps there.

Whereas on my parents' side, certainly, again, the goal was not to write a complete biography of these individuals. I always struggled with the idea of the word "biography" because I know it's being called that and I know it's being called memoir, but I actually don't feel very comfortable with those terms. I've accepted them, but I wish there was another word that we could use to describe this book. Indeed, I wrote it in a way in which I felt I wanted it to be read as a novel, because of the big gaps that I knew would remain, gaps both deliberate and unintentional. I can't know what I don't know.

In terms of how I achieved it for their side, I started with whatever it is that they wanted to tell me, stories they had been telling me their entire lives, parts of their life I hadn't heard about, and I just tried to get a few more details down. I tried to get as much knowledge as possible. I really just listened. Listening is essential for a writer, like observing is, when you're writing about others. Listening is about being present and allowing the other person to be. There were only a couple of reasons I would interject into their long monologues that I recorded. One would be if I really wanted to get a few more details, because I knew I had to elevate—I think that's the right word—I wanted to elevate these stories to literature and art. Not that stories themselves don't have value, but because that was what I wanted to do. I'm an artist. I wanted to make this into art. I just needed more on my palette, if you will. I needed some details on things. I would interject to get details of things, like colours of things or species or sounds or tastes. Things like that. But that's what we do. That's what writers do.

I would also interject if the stories were so difficult for them to talk about, not that I was learning anything new, frankly. It was just finding a way to get it down in a different way. Some of it did end up coming out verbatim. Little bits. But if it was getting really difficult or painful to talk about something, I would kind of shift it. Often, I was asking the same questions but for a different function. I would ask the brand name of my mom's bike, or the colour of it. I wanted to know those things, but I was also asking her so it would take her mind away from the trauma of a particular story for a little way, to just carry us a little bit forward or to try to perhaps recall some of the more present aspects of life. That's kind of how I approached getting down their stories. Because I am me and because I am narrating, even though it's in the first person, I absolutely wanted to enrich, I wanted to bring in a second generation, a second partition, and bring all of the richness that I have gained—I don't want to sound melodramatic—but all of the sacrifices they made, everything they did, most of which was for their children and for the betterment of their children, I wanted to use all of the powers I had gained in my life, which are so different from my mother's life, or my father's life in that I've realized many of the things he's wanted to do. I wanted to bring all that wealth and richness that I have in my life to bear on their stories, and that's where both the poetry and the science, I think that was the function of both of those things in the retelling of their stories.

I wanted to talk about narratives around Partition. You talk about how nothing you learned from your parents was new information for you. My grandfather's also a Punjabi Hindu, and his family had to leave their home during Partition, and they just did not talk about it when I was growing up. The writings I could find about it when I started to look were mostly just history books. It seems in the last few years, since the 70th anniversary in 2017, I've seen more things like your book, this concerted effort to get stories down as the generation who lived through Partition is aging. So first I was wondering how open your parents were to talking about Partition when you were growing up, and have you found in your research—or just as a person growing up after this generation—have you seen a shift?

Like your family members, they didn't talk about it very much at all. Most of my knowledge of Partition does come from films and books. One of the first ones, there's probably a couple out there, but they're like Gandhi, the movie, I remember watching that with my parents in the ‘80s. But it just kinda happens at the end of that movie, right? You don't actually see that much. It's not actually about it. There were a few iconic things. Certainly, above all, Deepa Mehta's film Earth, but it was in 1999 it came out. I do remember when that came out, it had a particularly big impact on me, but again I watched it on my own. I didn't talk about it with my parents. I really am thankful for those artistic treatments because they do allow people like us to have a window into partition, and I think that's one of the wonderful functions, if I may say, of art. They do allow us windows into things that people don't want to talk about, or you're unable to talk about. If anything, art is so wonderful and books are so wonderful for that purpose. That's what they're for, for learning about the lives of others. If my book serves as that function, that's wonderful. I think it will. I've encountered some second generation Indian kids who all kind of say the same thing, that their parents never talked about it, they don't really know anything about it, and how are we, as second-generation immigrant kids, this is not taught in the history books, how are we going to find out about it if not through literature and books and things like that? This is the way I feel like art can actually, you know, have an impact on society. Anyway.

So, Earth, there was an opening scene there are these young people in their twenties sitting on a blanket and having a picnic in Lahore, just as independence is being declared. It did allow me, first, not only to understand the time and place of Partition, but also the time and place of my parents' youth, which is also something difficult for us immigrants to imagine. My parents came from a totally different time and totally different place. It sounds so simple to say such a thing, but it took me writing this book to fully understand how different it is. And I knew it was different. That was the thing that propelled this project forward for me. I wanted to know. I wanted to be there. I wanted to go there, desperately. It's not the same as going to India today. It's not just place. I've been to India several times. I've been to where my mom grew up, but it's not as simple as doing that. It's time and place. When those two variables interact, it can be totally wild. It's really hard to imagine.

You asked if there's been a shift in the literature. I too very much noticed the media attention around the 70th anniversary of Partition. I'm grateful for that, for the media, all the Guardian articles, a few other things that came out. Hazlitt actually published a really lovely essay by Rudrapriya Rathore, and she mentions a few books in there that I already had come across. Has there been since then? I haven't noticed much, to be honest. There've been a couple of nonfiction books that have come out. There was a reissue of the collected works of Manto, and there's a film made about his life. He lived through Partition and wrote incredibly potent stories in Urdu that have been translated into English now, from the points of view of prostitutes and criminals and people in insane asylums. It was just an incredible window into Partition. There are still lots of books out there, if people want to read them.