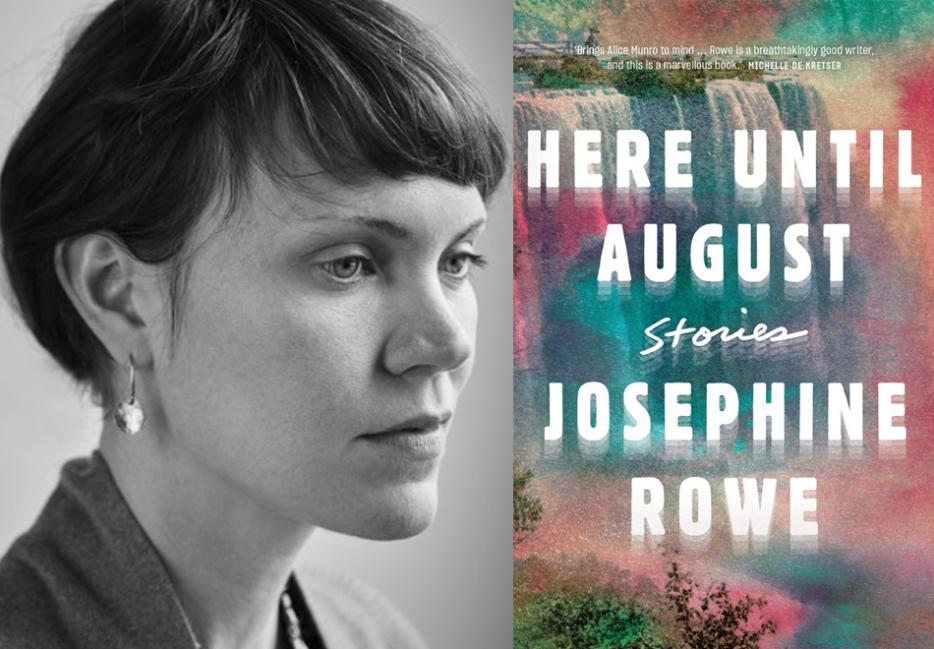

Josephine Rowe’s latest short story collection Here Until August (Catapult) is full of people leaving, returning, and biding their time. Seven years in the making, many of these stories take place all over the world: from Australia to the Catskills to Newfoundland. There’s an interiority in the work; of secret passageways, bated breath, family history and inside jokes reserved for old friends.

As a poet, Rowe demonstrates a dislike of wastage in her work: every word counts. Her debut novel—A Loving, Faithful Animal—is just under 200 pages, and explores intergenerational trauma through a group of siblings growing up in 1990s southeast Australia.

Josephine and I spoke while she was on assignment in Western Australia as a journalist, before returning to Melbourne for the launch of Here Until August.

Nathania Gilson: As I read the stories from Here Until August, I was struck by the Australian-isms that sung out on some of the pages: “runners,” “pissing contest,” “reffos,” “bogans,” “hauled arse,” “lark." What is it about this kind of colloquial syntax that deserves its place in a story (even at the risk of losing or confusing readers outside of Australia)?

Josephine Rowe: I’ve never really understood that a writer might run the risk of alienating or losing readers—especially those who’ve elected to read a book by a foreign writer—by using an unfamiliar word.

Reading—however you’re coming to it—is a willful act of discovery. Of engaging. So, I’m not sure who that reader is, but I hope never to be stuck in a lift with them. It would be a dreary wait.

That said, colloquialisms probably tell us something more pointed about people than standard language. For instance, the word “reffos” makes me cringe. In the story, it’s treated as a harmful and dehumanizing word—which it is. It trivializes the experience of dispossession; of unfathomable loss (of country, and more) while seeking to shrug off our national responsibility to extend asylum to those in need of it.

Not everyone who uses that word—children, for example, as is the case in the story—does so in full consciousness of its cruelty. But what does it say about Australia as a country for that word to be so prevalent in the lexicon?

So many of the characters in this new collection of stories are so attentive to language: they hear words as though they’ve “been kept in the wrappers they came in.” They compile mental lists of words that sound differently when spoken than they do written down—“vital and gleaming.”

In your own life, do you have any language-based rituals or systems that you use to collect words, sounds, sentences, or turns of phrase that catch your attention? How do you make the most of noticing things?

How to make the most of noticing things—this might be the perfect mission statement for much writing, and much of art.

I just write things down on whatever’s to hand—notebook, envelope, wrist—then often forget about them just as quickly. But your question makes me suspect I’m being left out of some terrific methodology of cataloguing.

Certain things I’ve probably internalized without consciously recording. The speech patterns and idioms of friends, or the various ways that English breaks when spoken as a supplementary language.

I remember studying your work at uni, and being shown evidence that published short stories need only be one sentence long, that more words didn’t necessarily mean better (or more interesting) narratives—especially from your early short stories and Tarcutta Wake.

These stories were published not long after the introduction of Twitter, which was envisioned at the time as “like texting, but not.”

I wonder what you set out to achieve—or rebel against?—at a time when short stories (or flash- or micro-fiction) may not necessarily have been in vogue, seen as profitable, or a thing to "aspire" to, as a writer?

Writing those earlier collections, social media wasn’t remotely on my mind (I was a latecomer to social media; also, the term “flash-fiction” always seemed like weird, time-poor branding to me).

I wasn’t rebelling, either, even though I was told often enough that I was doing something unpopular or unsaleable. But it was only ever publishers who told me that—“five-finger exercises,” one man dismissed them as.

I was just writing in the mode that I felt fueled to write in, and that I’ve always loved to read in.

We don’t have to reach very far for galvanizing examples of writers who are exceptional—and often at their best—in shorter forms: Yasunari Kawabata, Jayne Anne Phillips, Ali Smith, Lucia Berlin, Sandra Cisneros, Michael Ondaatje (in his early novels). Jorge Luis Borges, Raymond Carver, Eliot Weinberger, Janet Frame—pretty much any fiction writer who is also a poet, as they are more likely have the patience and the reverence for distillation.

The stories in August being generally longer (if not necessarily better or more interesting!) might have something to do with them being further from autobiography (which I’ve delved into elsewhere) but also simply the luxury of time.

I say “luxury” to mean something closer to a self-imposed effort towards patience. I don’t know if it’s because I’m older, or several years further into things. Thinking on it, perhaps there was a particular urgency early on—that the twenty-something-year-old writing those stories didn’t believe she’d make it to thirty.

Post-thirty (and then some), I’ve at least a slightly longer view: I quite like the process of a story accruing over many months, or years.

I think in many ways I’m working from the same instincts, with the same sensibilities—definitely from the same methodological disarray, and occasionally from the same sense of urgency—as I was with those shorter stories.

But if we were to break it down to say, the attention that's gone into a sentence, then there’s probably no difference between my approach to a long story or short: the sentence would be holding the same amount of time (and ghost versions of itself).

Several books into your writing career now, how do you motivate yourself to keep writing?

I was speaking recently with my oldest friend, a cellist, about how much can be meaningfully addressed (not just expressed) through our respective artforms.

Whether there might still be time to become qualified in something more practicably beneficial to the environment or to others. Or, are these vocations that we both came to honestly, worked shitty jobs to support, with no real expectation of ever making a living by them (even a modest, no-car-no-kids living) what we are beholden to push forward with? To find a way of ensuring they’re relevant, in the service of the right things.

(For the record, I don’t think it’s a bad thing to have a perennial crisis about this, so long as you keep moving.)

What keeps me writing is some blend of that innate compulsion, not quite articulable, and the desire to hitch it to something definitive.

And—shorter, straighter—I write because it’s the best means I have of figuring things out.

In the final short story at the end of Here Until August, a couple drives past a frozen pond. They want to walk out onto the ice just to see if it’ll hold their weight. Of the trust required to believe the ice will hold their weight, they remark, out of superstition: “It is magic in the sense that there is no metaphor you can build out of it that will not undermine its magic.” There’s a sense of being dumbfounded by nature there, I think. Wanting to be impressed by the force of it, but not necessarily getting wrapped up in how things might actually come into being. Earlier this year, you wrote a weather report on global warming for The Believer. In the piece, you name the environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht who coined the term “solastalgia” which was widely adopted as a watchword to describe existential crises brought about by environmental crises. I’m wondering how you grapple with writing about home, homesickness, and a sense of place in the age of climate change and the looming realities that impact our physical sense of where we come from?

While the stories in Here Until August do have human lives as their fulcrum, the non-human world—animal and elemental—is very present. And the characters in each story, even if they’re somewhat bulwarked by city life, are moved by these forces whether they’re conscious of it or not.

But these stories were collected over seven years. And seven years ago, like most of the attention-paying world, I was less afraid (at least in regards to the climate).

So much has happened, or come to light, in the intervening years that locates us in the tipping point, not simply bracing for it.

In The Believer essay I mention last summer’s news cycle—within the same report there’d be fires, floods, the mass death of fish in one of our most significant river systems. New colors appearing on the temperature map as record highs were consistently broken.

If the stories here are reflective of the concerns I have about those looming realities, then great. But I don’t think they speak as loudly to them as I presume my next book will. At present, I’m probably more likely to confront these things directly in essay and non-fiction. Which is not to say that they shouldn’t be a focal point in fictional narratives; absolutely, they should. Only that sometimes overtly assigning a character one’s own agenda can feel like a flimsy act of ventriloquism. After a point, the story resists. In non-fiction, that isn’t a problem. I don’t have to worry about whether it would be believable of X to think deeply and at considerable length about Y.

So much of your work reveals the thrill of being understood—and the devastation of being misunderstood. I’m thinking of in “Real Life,” the Yukon Jack girls, whose neighbours can never tell if they’re fucking or fighting. When the narrator in “Repairs” removes the “s” arm off her typewriter so she can’t spell her ex’s name. Instead, she types: “Bezt. Regardz. Cheerz. Xincerely. Thanx.” Short stories often come with intentional gaps or unfinished business—how does the form help you resolve or contain things that don’t necessarily work themselves out as you’d like to in real life?

It does help, but it might take a lifetime to get to the why. Maybe writing neither resolves nor contains these things, but rather opens to air, or helps to metabolize. My own clearest example of this were the realizations I came to in writing A Loving, Faithful Animal, my first novel, and a quintessential first novel in many regards (very close to the bone). But also, this is not the only reason I write.

Are there narrative forms beyond the short story and novel that you have experimented with and found a new voice in, or that you’re interested in exploring?

I’m not sure about a new voice—for better or worse I think I’m fixed to this one, at least authorially—though I do hope characters’ voices are distinct from this.

But I do write in other forms—and perhaps feel most myself in fragmentary, genre-eliding works. But where to house these? So, they don’t often make it as far in finding an audience, and that’s okay. Once something’s published it’s essentially set, and there’s something comforting about the prospect of works that might stay malleable and in-progress for an indefinite period of time, something you may never have to call finished.

(And also, I should say that I appreciate very much the outward attention that an essay or profile requires, if we might include these as narrative forms. Being brought out, blinking, from the grainy introspection of fiction. I find it’s necessary.)

What advice would you have for young writers who doubt themselves and the stories they want to tell?

Firstly, that doubt can be a formidable ally, indicative of many favorable and necessary attributes; that you take your work and the story you’re trying to tell seriously. Probably that you have a moral compass, believe in accountability, etc. Of course, doubt can be entirely inhibiting, so we have little choice but to make a friend of it.

I say this with the caveat that some doubt is well-founded, so we’re continually tasked with determining whether we hesitate because we are ill-equipped, or because we are simply afraid, and undervalue our voices.

A friend sent me a Georgia O’Keefe quote a couple of weeks ago: “I've been absolutely terrified every moment of my life—and I've never let it keep me from doing a single thing I wanted to do.” I can’t claim the same, exactly (of never allowing fear to scupper my ambition or desire) but it’s a good stone to have in your pocket, remembering that the most courageous and dedicated people we know and admire are generally also scared witless, in one way or another.