My grandparents spoke a makeshift pidgin known as Finnglish: a combination of Finn and English, in which the latter becomes the former through the liberal application of extra vowels, as in streetcarii, a Finnglish noun meaning the electric transit vehicle that runs on Queen Street in Toronto. There are no rules: it’s an immigrant’s language of survival and adaptation that you make up as you go along, paradoxically an attempt at clarity through utter confusion. Still, it helps weather the shock of living in a new place without losing your identity: you hang onto a few shreds of your old life while you adapt to a new one. After all, who you are depends on the language you speak.

In 1995 Diego Marani, an Italian translator working with the European Union, coined the term Europanto to describe a language in which Dutch, Spanish, German, English, and French can all vie for attention within a single sentence, an artifact of globalization and the rush to a common, borderless culture on the continent. Unlike Esperanto, which is a language unto itself, Europanto borrows from what already exists. It is a language of modern social panic: throw everything you can at a communication problem, from every language you can get your hands on, and hope for the best. “In der Europa des future,” he wrote in a handbook for his new language, “Europanto coudde mucho helpful esse por manige mensen inderfacts.” The idea went nowhere. It was received as a joke that grew more tired on each retelling, which is not to say Marani wasn’t onto something: it’s just that people don’t like to think that their language, and therefore their idea of who they are, can be as fragile as rice paper. He gave up promoting Europanto a few years ago and turned his attention to writing novels.

In 2000 Marani wrote New Finnish Grammar, in Italian, since translated into English (at the this point it may be helpful to start your own linguistic org chart) about a man who’s forgotten everything, including the language he speaks. He is found unconscious on a dock in Trieste, in Italy, during the Second World War, and taken to a German hospital ship where the medical staff are flummoxed: he can’t speak, he can’t remember how he got there, he can’t understand a word he hears. A clue emerges. He’s wearing a Finnish sailor’s coat. A name is stitched on the collar: Sampo Karjalainen. A doctor on the ship, named Fiari, himself a Finnish ex-pat, takes Sampo on as a project: it is his intention to teach the man his native language and return him to Finland, where he can reconnect with his roots and reconstruct his memory.

The problem, and it’s no spoiler to reveal it since we learn of it in the first few pages, is that the man found in Trieste is not Sampo Karjalainen at all, nor is he a Finn. He’s an Italian, the victim of some random crime in which his clothes are swapped. But no one figures this out until much much later, so to Finland he goes, to find himself. “Since language is our mother,” the doctor tells him (once Sampo has acquired enough Finn to understand what he’s saying), “try and find yourself a woman. It is from a woman that we come into this world, from a mother that we learn to speak. Fall in love, give of yourself. Switch off your brain and follow your heart. You must fall in love with a voice, and with every word you hear it utter.” Sampo meets a nurse and nearly falls in love except for one peculiar hurdle: the words she speaks make sense, technically, but it’s as if his heart can’t manage a translation.

“I had a distinct suspicion that I was running headlong down the wrong road,” he tells us (in a diary written after the fact.) “In the innermost recesses of my unconscious I was plagued by the feeling that, within my brain, another brain was beating, buried alive.” Sampo Karjalainen is figuring out that he’s two different men: the one before the incident in Trieste, and the one invented by Dr. Fiari through the makeshift scaffolding of a new language.

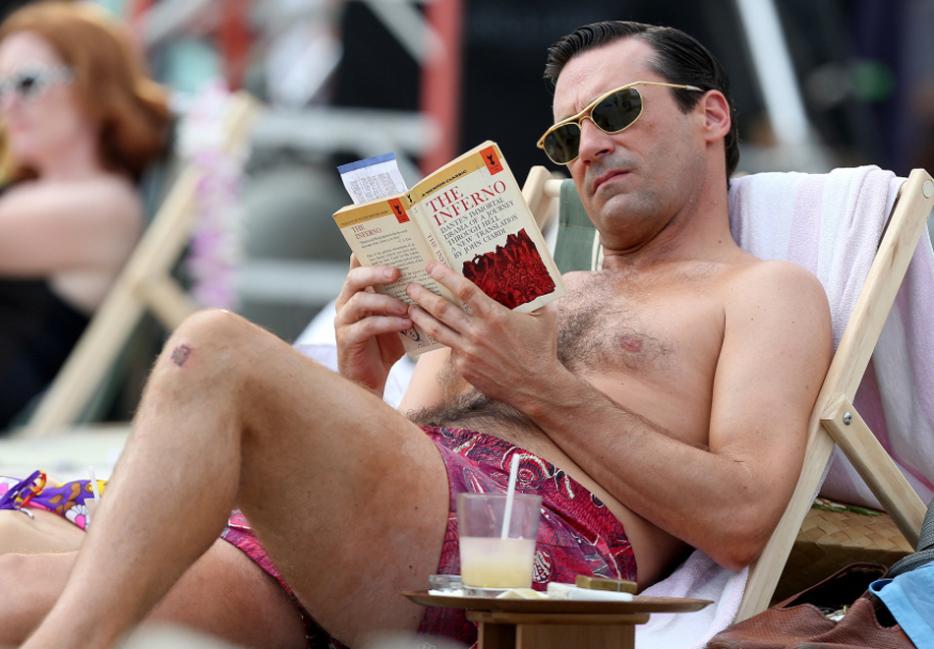

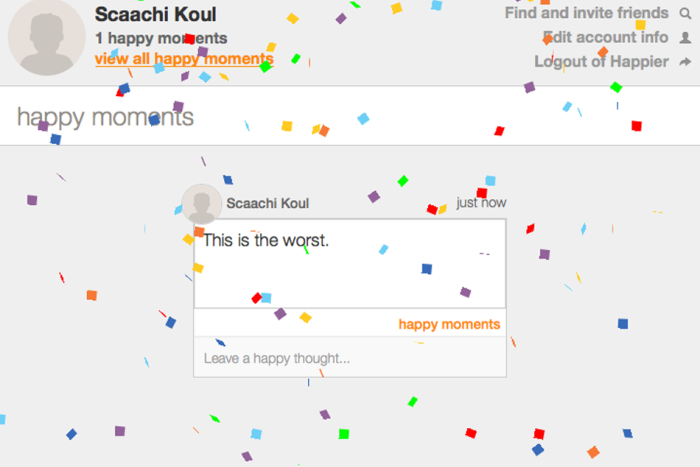

There’s no duplicity here: he’s not Don Draper out to erase an unpalatable past in order to succeed in business, marriage, and American life (and even Don Draper can’t escape the beating of that buried brain). He just wants the truth. But which one? The real truth of his past, or the truth of the life he’s been gifted, through a new language, a new home and, even in the midst of war, the promise of love and a future? Marani’s job as a novelist is to push Sampo (or whoever he is) into making a choice, only to remind the reader how impossible this task would be: we are all a Europantic mish-mash of memories, dialects, false fronts, double-dealing, lies, and confessions. Who we are at work, at home, on Twitter, in our dreams, on the therapist’s couch and at the bar are all very different people. To choose one as the truth of who we are is folly.

In the short parable “Borges and I,” Jorge Luis Borges plays with the idea of identity by imagining there are at least two of him: the Borges who writes, and the Borges who is written about. “My taste runs to hourglasses, maps, eighteenth-century typefaces, etymologies, the taste of coffee, and the prose of Robert Louis Stevenson,” he writes. “Borges shares those preferences, but in a vain sort of way that turns them into the accoutrements of an actor.” The reader might think of a picture of himself as a child, with whom he no longer has much if anything in common, except certain preferences and tastes: they are two separate people, the child and adult. “So my life is a point-counterpoint, a kind of fugue, and a falling away—and everything winds up being lost to me, and everything falls into oblivion, or into the hands of the other man. I am not sure which of us it is that’s writing this page.”

This is Sampo Karjalainen’s dilemma: not who am I, but which one of at least two possibilities am I and how do I bring them together? Marani and Borges both count on some recognition that this, in small measure or large, is also the reader’s life. Each of us is a streetcarii full of fellow travelers who don’t always get along or hold the same values, but somehow we teach them to speak, and agree on, the same pidgin language.

The Lost Library: forgotten and overlooked books, films and cultural relics from Tom Jokinen’s overstuffed Ikea bookshelves.