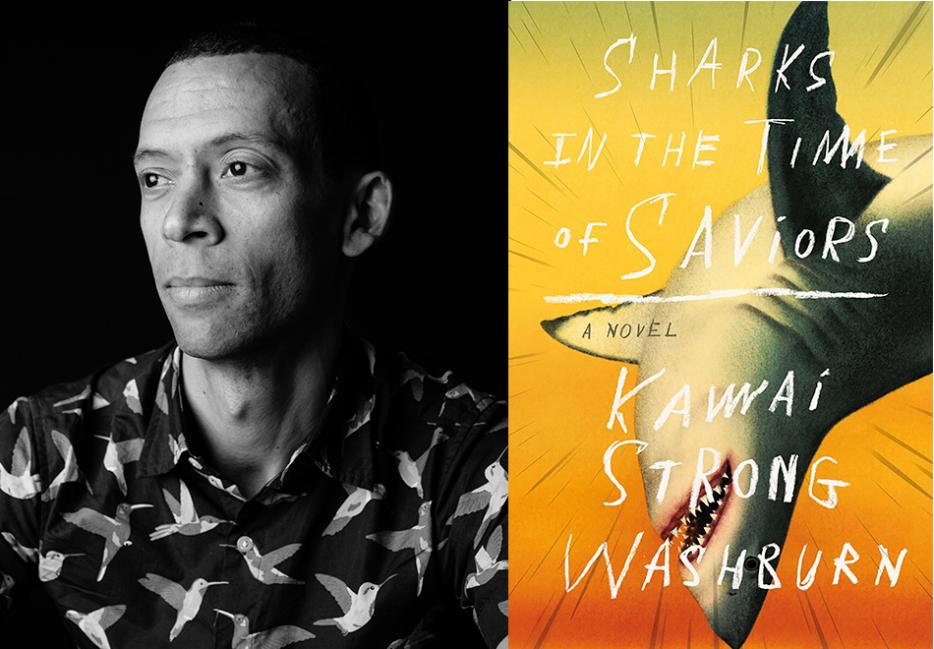

Sharks in the Time of Saviors (McClelland & Stewart), the debut novel by Kawai Strong Washburn, was the first book I’ve read. At least, that’s what it felt like. After two months in lockdown, unable to focus on little beyond refreshing the news, I began his book—first out of obligation (I had to read it for work, after all), which quickly turned into deep engrossment. Sharks is a surreal family drama that functions as its own best argument for the necessity of art. At the centre are the Floreses, a family of five that weave their own narratives within the larger mythologies of their native Hawai'i.

The novel opens in 1995 Honaka’a when Nainoa, the youngest Flores son, falls off the side of a cruise ship, only to be rescued and returned to his mother by a passing school of sharks. This moment throws the family into a media spotlight, rescuing them temporarily from their financial troubles, and marking Nainoa as special, touched by the gods. He carries this burden of specialness with him as he enters adulthood. Washburn alternates narrators between chapters, letting Nainoa’s story unfold alongside his siblings: the brilliant Kaui, who despite her exceptional test scores still feels like she’s lacking as she follows in her brother’s shadow, and Dean, a talented basketball player who hopes his own burgeoning college athletic career will be the thing that ultimately pulls his family up through class stratification. The siblings leave Hawai’i to make their way on the mainland, trying to become the people they feel they’re supposed to be while never truly able to leave their homeland behind.

Washburn was born and raised on the Hamakua coast of the Big Island of Hawai'i. We had plans to speak in person, before his tour, like almost all events, had to be cancelled. Instead, I reached him by phone earlier this spring in Minneapolis where he lives with his family.

Anna Fitzpatrick: It's a weird time to be launching a book, especially one that deals with illness and community and social inequality so head-on. What has that been like?

Kawai Strong Washburn: I think for me more than anything it keeps what really matters in perspective. On one hand I appreciate people who have still been engaging with art and have seen that as a way to have some relief and release and to enjoy the sort of things that remind us of what makes life great. Art can be this lovely experience. Even though we're in the middle of an incredibly challenging time, that doesn't mean that art is completely irrelevant. It's nice to have people reading the book and enjoying art for art's sake.

On the other hand, it's nice to be reminded that there are things, which I try to keep in perspective anyway, that the world has a lot of incredibly important challenges in front of it, and those things can render what feels like a normal daily life obsolete in a moment. It's tough to have a book come out at a time when people are scared and anxious and threatened in terms of their health and everyone's locked down, so talking about a book feels kind of strange and beside the point, but for me it's like, that's okay. The world has bigger problems right now. So, to the extent that this book coming out is overshadowed or bypassed because of this pandemic or what it's doing to this world, not only is it beyond my control but I totally understand why that would be the case. I keep both those things in mind at the same time.

The people I've been talking to have either been doubling down and reading as an escape, or they just cannot focus at all on anything. What has your relationship to art been like?

I think the thing that has been really stretched for my wife and I is that we have two children that are really young. Our older daughter is six and our younger daughter is two. We're both fortunate enough that we still have our jobs and we can work remotely, so as a result we're both still working mostly full-time, but we're also having to take care of our two children at home and trying to keep our schooling going for our six-year-old and trying to find ways to engage and nourish our two-year-old. Trying to balance all those roles leaves very little personal time to do things like read. I still find time and space to do that, even if it's as simple as a poem a day or things like that. I'm trying to get some nice time to enjoy poetry, or when I do have a spare little bit of time in the evening, I really enjoy it for that brief period of time. I don't think it's affected my ability to focus on reading, I just have less time to do it than I'd like.

You would have been travelling right now if this wasn't going on, right?

I think I would actually be in Sydney right now. I was going to be part of the Sydney Writers’ Festival. It's hard to remember. I've sort of jettisoned that whole alternative future. It's been ejected from my mind. I would have been in either Australia or Hawai'i right now for about the next week or so.

As someone who writes about books, I always have that instinct to put them in a category, even with the knowledge that genre and labels can only go so far. Your book has been dubbed magical realism. How do you feel about that?

I love books that are labelled as magical realism, and I think in general I'm cautious about labels that are applied to books. I take those as a general, as someone that tends to categorize a book that may or may not be easily categorized. I don't really mind the book being put into any category of this or that, unless it would be in some way insulting, and I don't think that's the case with magical realism. The novel does what magical realist books often do, which is it takes events that could be otherwise considered fantastical or "magical" and tries to have those things be rendered in a world that feels like an otherwise "real" world. The world itself seems like it applies the normal rules of physics, and it's a place that we all recognize as being the current times, and, yes, there are these magical or supernatural or unexplainable events that are occurring in that space. I think that at some level the book is trying to do that. I'm trying to write the portions that have to do with supernatural or magical elements [in a way that] that leaves a little bit of interpretation there for the reader, I'm hoping. You can see these things happening, and the question becomes, is this a supernatural event, is it somebody having a hallucination, are they interpreting things in a very specific way? Since this is through a rotating first-person perspective, and each person has their own interpretation of events that are happening to them, it gives the reader some room to interpret those things however they wish. Including that, as well as using language that renders those moments not as fantastically as they might otherwise have been, hopefully preserves that fun play between something that is maybe real and not real.

During the passages that have such ambiguities, do you have your own master narrative in mind?

I certainly have my own interpretation of what I think of the story, but I think leaving that room... once a piece of art leaves your hands as an artist, then there's no way you can control the interpretation that other people will have. Art in general, it's a conversation that happens across space and time. Like any conversation, all the parties involved are participants and the extent to which they do or don't engage with each other, it colours the way in which they have that conversation.

Knowing that once the book goes out into the world, people are going to have their own interpretations of it that I may or may not agree with, that's just how art works. I wanted to write this book knowing that that would be the case, and I have my own interpretation of it, but I could write it in a way that doesn't force the reader to come to some specific conclusion because I want them to have that conclusion, then it makes the reading experience hopefully that much richer for readers that are engaged with it. So yeah, I have my interpretations of what's there, and I certainly have my belief of what the story describes, but other people might have different things. It's up to the reader. I don't know what they see at the end of the book, and what they think has happened or hasn't happened, but that's no more or less correct necessarily than my interpretation.

You're writing a book that fits into a larger tradition of storytelling and mythology. I was reading about Hawai'ian mythology and how it pertains to sharks—something I knew nothing about going into your book—and I was wondering how large these stories loomed in your mind, both growing up and while you were writing the novel.

Large in both cases. One of the things that I loved growing up in the islands, and one of the things that I think makes the culture of Hawai'i so rich and powerful, is the number of legends and myths that deify the natural world in a way that both upholds the interconnectedness of all things, of humans and the natural world, as well as rendering those things with the sort of awe and power they deserve. Growing up in the islands, yeah, there were legends all around and just interpretations of ongoing natural events through the lens of mythology and legend. When there's volcanic activity, people talking about that activity as a manifestation of Pele, who's the goddess of fire and volcano, that's the islands. Growing up there, that was the way I experienced the islands. Having that mythology as part of the daily life. And part of a larger confluence of different traditions, because the islands are full of immigrants from different countries and different ethnic backgrounds. The traditions and mythologies of those ethnic groups and those immigrants are mixed in with the myths and traditions of the islands, and that makes for an incredibly rich and powerful and just wonderful experience as a child. Just exchanging ghost stories with your friends, and getting exposure to all these different cultural traditions.

When I was writing, that was one of the centre-pieces of the work, trying to bring that feeling to life. To express that, but also to use it as a vehicle to talk about what I had experienced in the United States in terms of the larger cultural... you could call it a disconnect, or friction. It's also one that has to do with the value of the greater United States in terms of how the natural world is often perceived, and how you can have a capitalist American perspective on the natural world as an expendable resource. Growing up in a place like the islands, I never felt my relationship with the natural world was defined on those terms. It was defined very definitely. That's one of the themes of the novel. As an expression, of the facet of the disconnect between people from other traditions and the central American myths and traditions that exist. That was how I wanted to take the things I experienced as a child and express them in this book as part of those larger thematic elements.

That theme comes through with the three children characters in the novel, and their struggle to feel connected to their roles within the natural world and the mythologies they inherit, while also trying to forge these individual identities on the mainland. Speaking to that, what does it mean to be a saviour?

In my view, and I think it comes through in the book as well, that is an incomplete idea. It speaks to individualism often, and for most people the concept of a saviour is something that speaks to a certain amount of individualism and exceptional individualism, in that there is one person whose abilities and fortune and characteristics of that specific individual are so much greater than anyone else, or even the collective. That is going to be the person to make an important or significant change in the world. When you look at some of the most significant changes that have happened, even just within the United States let alone the world, it's really more often the result of communities and people reaching out to each other and forging strong bonds. Having built those communities and making the expression of those communities lead to change, that's really where you see a lot of the most significant change happening in the world. And yet after the fact, people will often prescribe the change as having occurred as the result of a single individual. There's always this narrative that emerges when there's a change happening in the world, to try and simplify it. When you can simplify it by attaching the larger narrative to one specific individual, that obscures the larger collective work happening in the background. The idea of a saviour in my mind is that sort of incomplete story, where you try and take what's typically something that's of a larger collective experience, and try to ascribe it to a specific individual.

This is such a different context, but I was thinking about it while reading your book. So many of these frontline workers, healthcare workers, service workers, there's this rhetoric that they're heroes. We're calling them saviours to absolve the collective responsibility of, no, we have to take care of our people. Not just call them heroes, but give them support and protection to do their jobs safely instead of being like, "Alright, bye, go save us."

Exactly. I think that's one of the biggest challenges, in my opinion, with an economic or socioeconomic system like capitalism: the way in which it obfuscates things. You eat food that you get from a grocery store or restaurant, and there's so much that's hidden in terms of all the different people that have contributed to that food arriving on your plate. It's the same thing with clothing, with all the goods and things that are part of the material comfort of a late modern capitalist society, so much of that is hidden. You don't see the socioeconomic or environmental cost. You just have this final product that all of the stuff along the way, people and animals and natural resources, have been exploited for that thing to arrive at your doorstep. All those things are hidden.

I think something like the COVID-19 Pandemic, it does what you're describing. It exposes the underlying interconnected nature of everybody's lives. The vast majority of people are living their lives in connection with other people whether they want to recognize that or not. Something like this exposes this very quickly, where there are things being provided to me at other people's risk and expense, and I cannot ignore that now. That comes back to the same idea of saviours, just the individualist narrative more generally, which is one of the things this book is looking at. The narrative of the family carries for a portion of the novel has a lot to do with trying to figure out whether this individual narrative, the story of our family, is it really all about just this one miraculous individual, or is it something larger than that?

It really interrogates how isolating it can feel to be seen as a saviour. It's most clear with Nainoa, but also with Dean in the last act, trying to provide for his family in his own isolated way.

Nainoa as a character was a struggle because I wanted the characters to all be complex, to have their faults and failures, and not to have any character be entirely good or entirely bad but to make characters that were complex. Have the same sort of internal contradictions that we all have. In the case of Nainoa, the thing that was a struggle was trying to find a way to have him have some level of privilege and arrogance. He receives this level of attention and prestige as a very young child. More often than not, at that age when you receive that level of attention and prestige, it's really hard not to come away with some level of arrogance, or feel like you're deserving of the things you're receiving in cases where you're not quite as great as everybody is saying you are. Trying to render him with some level of arrogance but also trying to recognize the burden that comes along with that, the same as it would be for any young person that's placed in a position of elevated attention and prestige, to balance those two things.

In earlier drafts, a few people had read it and were like, "I kind of don't like him." I think that was because I biased a little bit too much towards arrogance and privilege. I tried to find a way to balance that, bring out a little bit of a balance as well. Anybody who's in a situation where they're part of a family in which economic hardship is central, when you have a family that's struggling, and you have something that can potentially provide economically, that's an incredible burden to have. To be somebody that other people are depending on and have an expectation to deliver something better than what you have currently. That's a burden. I think anybody who comes from families where that's the case, where they're somebody that's achieved above and beyond the family's current station in life, and the expectation that will help carry the family farther, that's hard.

That burden of potential is something all the kids experience to an extent; being told you're destined for greatness, either academic or athletic or being a saviour with healing powers.

There's a narrative the children have of themselves. I think the novel also examines the idea of a self-narrative versus an external narrative, and how those two things can be conflicting as well, and how you can have an idea of who you are and the story you tell yourself about who you are, and it can be very different than the story that other people are telling. Other people can be trying to define you a certain way. There can be resentment, and conflict, and delusion in all of those things. The novel tries to look at the ways in which each of the children in particular, the siblings, are struggling to define themselves on their own terms, but those terms are also in reaction to that initial miraculous event that set things in motion. I think anybody who's been in a family, who's just part of a family dynamic, right, everybody has an idea of who they are and the story they tell themselves within the context of the family, and it's usually a different story than what all the families have about you or have about each other. That was one of the things that was part of the story as well.

I'm really interested in the way you used dialect, especially the Pidgin that Dean speaks. I think there are so many misconceptions about slang that doesn't follow dominant grammar rules, that there is no grammar to them, but you really captured the consistency of that language. Is that something you researched?

Certainly, growing up, that was the default language where I was from. I grew up in a rural part of Hawai'i, that's what everybody was speaking. Everyone was swinging some different level of Pidgin. You can have it dialed up or dialed down, you can have people operating at different levels. It can get thicker depending on who's talking to who and in what situation and things like that, which is lovely and wonderful. I love that about language, the way Pidgin is an adapted form of English that also incorporates slang and language from a variety of different countries, cultures, ethnicities, in the sense that you can have like, Japanese words or Filipino words or Portuguese words, that are part of Pidgin along with words from Olelo Hawai'i, the native language of Hawai'i. You can have all those things mixed together, along with all these interesting grammatical constructions.

I wanted to represent that in the novel, but also one of the things that might be controversial, that some people might think is a failure on my part or a blind spot is the fact that, the way that it's rendered on the page breaks with how you might traditionally render it. If you look at a lot of literature from the islands that is written with Pidgin, it will have very different spelling and punctuation than what I have with my rendering of it in this novel. That was intentional on my part, because as a reader, I read visually in a way that if there's too much punctuation and the words are spelled too phonically, it can really trip me up. If you take a bunch of words that I'm used to reading one way and the spelling is completely different, and there's punctuation, and the grammar has been constructed in a different way, it can be hard to settle into it and read through it. I think it's something about the way my eyes process the marks on the page. So, when I wrote this, I was writing this with myself as a reader primarily, because I didn't have a bunch of people I was working with on the book or that were reading along with me. When I wrote it, I was taking that into account. I wanted to take the language and render it as truthfully as possible in terms of the rhythm and the sound, while also not over punctuating or chopping up the spellings in a way that made it really hard for me, visually, to read it. I think there are probably some people who think that that is not an accurate depiction of language, which I can understand, but my work on that was very thoughtful and came from a place to incorporate my preferences as a reader along with the idea of the fluidity of the language. I also think you can have a variety of ways of rendering Pidgin on the page, and none of those is correct or incorrect. They're just different renderings. It's one of the things that makes it such a wonderful language.

I can understand a protectiveness people may have, especially in what gets depicted and what gets left out in dominant narratives about Hawai'i. To me it speaks to the need for having more stories, more narratives, more voices coming out.

I think it also behooves the readers who are interacting with the art to recognize that it's impossible to pin the universal on any specific story. You can't take the representation of a place or a people as something that can be universally depicted. It's impossible. I think the thing that happens, with underrepresented stories or places, people are like, "Oh, this must be speaking to the entire truth of this place, or this community, or this people." It's no more the case for something from Hawai'i than it is the case for something from Australia or Nigeria or like, Montana. There are just a plethora of stories and experiences that people from those places have had, with a diversity of experiences and opinions as a result. The life that somebody has growing up in Honokaʻa is going to be different than the life somebody has growing up in Kalihi or Nānākuli or Honolulu or Wailuku. These are all different cities and towns in Hawai'i, by the way. The idea that this story which is set in Honokaʻa and other parts of the islands is somehow going to be universally representative of Hawai'i, it's impossible. As people recognize more and more stories need to be told from different places and perspectives that are underrepresented, we also need to realize those stories themselves can never be the perfect representation. They are just a singular, subjective representation.