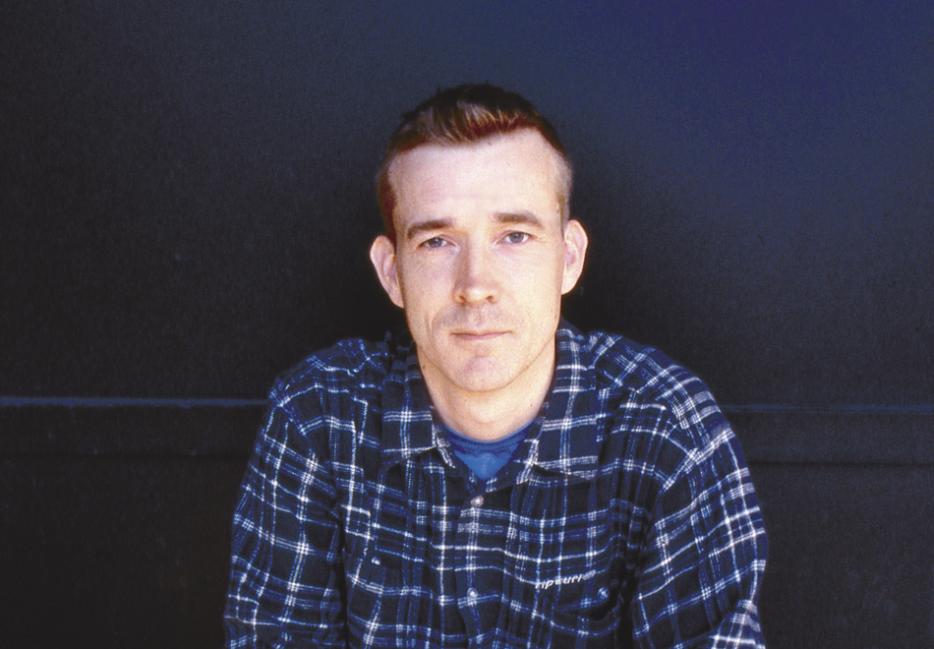

Somewhere, right now, a feverish dissertation is being written about intertextuality in David Mitchell’s fiction. His newest novel won’t disappoint the scholars: characters move between the six sections of The Bone Clocks in Mitchell-esque ways, and another couple of favourites are reincarnated from previous novels. But some of the more alluring Easter Eggs in The Bone Clocks are extratextual—the honesty, if you will, that makes the lie convincing—especially given that the time frame of the novel largely mirrors that of Mitchell’s own life. During a recent visit to Toronto in August, we got the chance to ask the author about some of them.

You’ve mentioned that after several trips to Canada on book tours, you wanted to bring it into your novel as a setting, which you’ve done in The Bone Clocks. You’ve also said that whenever you’re travelling you write things down as “textual photographs.” Is there anything that leaps to mind for Toronto?

Just walks and sort of urban hikes around the city with one or two Canadian friends. I’ve only spent a few days of my life here, but things that stick out would be a walk through Chinatown a few years ago, the [Bata] Shoe Museum, and looking rather wistfully at the Toronto Islands out on the lake: wanting to go there, but like the shores of Utopia, you can only see them and can’t actually get there. I never have time and I haven’t made time—maybe next time. Problem is, with the Harbourfront Festival [in October], it’s quite a chilly time of year, and I don’t want to go jumping on boats into the lake.

Maybe next will be Montreal. Since I’ve set some off-stage scenes there it would be good to go visit, take some textual photographs of that city, and put them on-stage.

Speaking of Quebec, your French-language publisher there seems to have made a cameo in The Bone Clocks.

Yes, that’s right. Antoine Tanguay. It’s such a fantastic name. You can’t make names like that up: you can only find them; observe them. Write them down on the page of your notebook, which I call my name bank. And when the time is right, wheel them out and put them in. A little sort of stud of realism, because how can someone with a name like that be made up?

And does he know that he’s now the fictional voice of a late night radio presenter in Switzerland?

I think he might have been alerted to this possibility, yeah. It seemed like the right thing to do at the time, and it still feels like the right thing.

Another cameo is Toby Cox, the owner of Three Lives & Company bookstore in Greenwich Village.

He was very good to me as a totally unknown author of Ghostwritten and Number9Dream, and invited me to his bookstore to do readings. I’m very grateful. I don’t want to sound immodest, but it’s a bit small for the audience that would like to hear me speak these days, so instead of going there I thought I would locate one of the horologist’s safe houses above his store.11Horology: 1) the science of measuring time; 2) the art of making instruments to measure time; 3) something altogether more than both in The Bone Clocks. It’s only two or three stories high—the building it’s in—so I make an imaginary top story which is where those scenes are set. And Toby is seen leaving the building at night as well, so it’s just a way to say thank you for his support in the early days.

It’s as if what I’ve written actually becomes a memory that’s rattling around in my brain, and it bounces off me at a particular street corner or sitting in a particular bar.

In another of the New York safe houses, there’s a painting by A.Y. Jackson on the wall. His work is very famous in Canada but less so elsewhere. Was this a painter with whom you were familiar before writing this book?

I’m friends slightly with [Canadian writer] Wayson Choi, and when I was here last year he and his friend took me out to the Group of Seven Museum on the edge of Toronto.22The McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg: A.Y. Jackson is buried in the small cemetery on the McMichael grounds. There’s a river and a beautiful gallery with a restaurant: we just had a lovely day there, and the artwork is beautiful. I could have spent all day there—well, we did spend all day there. So, I like to pepper this somewhat fantastical tale, especially that section (“The Horologist’s Labyrinth”) with morsels of reality. Perhaps to make the fantastical elements easier to swallow and digest.

When you return somewhere where you’ve set a book, does it change your experience to go back there—now that you’ve written about the place in absentia?

I suppose it does, though only in the same way as when you go back to a place that you already have memories of: you sort of bump into those memories on certain street corners or in certain absent-minded moments. It’s as if what I’ve written actually becomes a memory that’s rattling around in my brain, and it bounces off me at a particular street corner or sitting in a particular bar. But I guess we all have this experience with our memories if you’ve been living somewhere for a long time. That’s where I met I met that person; that’s where I had that meal; that’s where I had that argument; that’s where I was dumped; that’s the bar where I was dumped that time, etc. So there’s not much of a distinction in my mind between a scene I’ve written and a scene I’ve lived through—which makes sense, I suppose, because often scenes I write have been pieced together or melded together with scenes I’ve lived through.

The time period covered in The Bone Clocks coincides with that of your own life—at least up until the story shifts into the future. Holly Sykes, the character that ties the novel together, was born in 1969, like you. When using pop culture references (such as the bands Holly listens to), did you tend to reference your own favourites, or did you try to create a more objective representation?

Two parts to the answer, I suppose. Yes, Holly was born in the same year as me: you do that just to give yourself a rest from research. I had enough to research in the book without needing to research ’90s music—which I don’t know much about compared to my knowledge of music of the ’80s, when I was listening so avidly (and indeed was in the country as opposed to being in Japan). As to things I chose for Holly to like? Yeah, you want to like your main character. She makes mistakes: she isn’t always as critical as she should be and doesn’t always view things as objectively as she should. But on the whole I did want her to have good taste—what I’d call good taste—and to be a musical critic of some distinction. She thinks she is.

There’s an album called Fear of Music by Talking Heads, for example, that still sounds great now—probably sounds better now than it did then, I think. So I gave her that to be the sort of musical totem of her year, rather than something more ephemeral and trashy. Arguably it would have been better to have given her something ephemeral to show that she is sort of a creature of her time, just as we are creatures of ours. But the price to pay for that is that the reader will have no associations whatsoever with something ephemeral because it no longer exists and you probably can’t even get hold of it anymore.

There are a few albums referenced that may not be “canonized.” One example is George Michael’s Listen Without Prejudice Volume 1, which is not an album that people talk about an awful lot but was very popular at the time.

Well, you remember it, so it hasn’t fallen by the wayside completely. It’s not necessarily the centre of my musical taste, but they’re strong songs, they’re well-written, and he’s a gifted vocalist—even if you don’t like his music, and that’s fine. So I suppose what I’m saying is that I dispute your implicit claim that Listen Without Prejudice falls into the ephemeral and trashy category—sir!

[Tugging collar] Anticipating some of your coming interviews here: one intriguing character is the fictional author Crispin Hershey. His reputation in the novel exists alongside McEwan, Rushdie and Ishiguro—and many will think he shares some “outspoken” similarities with Martin Amis.

Not going there, sorry, and I will say that no—he isn’t Martin Amis. He’s a composite of all sorts, including aspects of myself. If people want to find evidence that he’s this figure or that figure or that figure, then they can and will—and I can’t have the last work on what they find. But I would like the last word on my sources, and my last word is that Crispin Hershey is a composite novelist made up chiefly of the worst aspects of myself, but exaggerated and caricatured. So there’s much more of me in him than anyone else.

Was it fun being able to speak through him?

Massive fun! I loved it! I loved writing Crispin Hershey—he was hugely enjoyable to write. All the things I want to say or have wanted to say but couldn’t and daren’t, and are too timid too or just too polite to. I didn’t have to worry about that with Hershey: I could just let him say them for me, and not have to take the consequences. …I hope I don’t have to take the consequences.

All the things I want to say or have wanted to say but couldn’t and daren’t, and are too timid too or just too polite to. I didn’t have to worry about that with Hershey: I could just let him say them for me, and not have to take the consequences.

But then Crispin also has quite an arc within that section: the way the reader will likely feel about him towards the end is very different than at the beginning.

Well if he’s only a caricature, that’s fine for a short story, but it’s not for a novella. He does have to move and evolve and go on a journey, and his is from misanthropy and hateability to something more complex and subtle, and redeemed at the end. Holly is something of a redeemer—not so much in the first section but in later sections in which she appears—she seems to be able to flag up the better men within the men she meets. And that applies to Crispin, certainly, and he’s a better person because of her.

Though these various sections—or novellas—work together in a coherent whole, did any particular storyline come to mind first as you began writing The Bone Clocks?

I wanted to write about Iraq. I wanted to bring Marinus back: even when I was writing Thousand Autumns, I sort of knew what he was—but I didn’t want that to be explicit because then Thousand Autumns would be more of a fantasy-historical novel than the historical novel I wanted it to be and felt it to be. So the Marinus component was there from an early stage. The final section, set in the 2040s, is sort of an expanded version of a story that I first read here in Toronto when I was on the road for Thousand Autumns at the Harbourfront Festival, in fact—so that was there right at the beginning as well. Then it’s a combination of having destinations that you know the narrative will be going through and ones that you find on the road along the way. When you get to a certain point, it gives you a view of a good place for the narrative to veer off towards.

In the Iraq section, it’s striking how the near-past can be just as strange as the near-futures for which you’re known. Both resemble our time, but are off-kilter somehow. The “present” of the Iraq section wasn’t that long ago, but there’s this sense of—wow, that really happened.

Yeah, Ed [the section’s protagonist] is in Brighton for a family wedding, but his mind is still in Iraq. Isn’t it fascinating how cultures change, and attitudes shift, and narratives about military intervention or social attitudes—the narrative towards LGBT, for example—have shifted so, so much since the 1980s? And in what I’m afraid to call the more civilized parts of the world, at least, attitudes to autism. They shift all the time, these currents and eddies, and from day to day you don’t see that much change, but it only takes a few years and you see “Wow, did we really do that? Did we really think that? Did we really take that for granted?” Endlessly rich stuff.

Continuing with autism in particular: your wife translated Naoki Higashida’s The Reason I Jump into English, and you wrote the introduction for that edition. How have attitudes and perceptions about autism changed for the better since Naoki’s original publication?

I can’t speak too much about Japan, but certainly in the UK and Ireland, which is sort of my home zone—you can now find dentists and hairdressers or GPs who “get” autism. Even the ladies who work in our local supermarket know our son and know what autism is about much, much more than they would have ten years ago. And it’s partially due to books like Naoki’s that contribute to the shift and help people to realize that autism isn’t about Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man, and it’s not about The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime, either—which are both fine pieces of work, but we need more than that to get our heads around autism. And to dissipate our ignorance, which makes it even harder to live within an autistically wired head than it otherwise would be: our ignorance aggravates the problem.