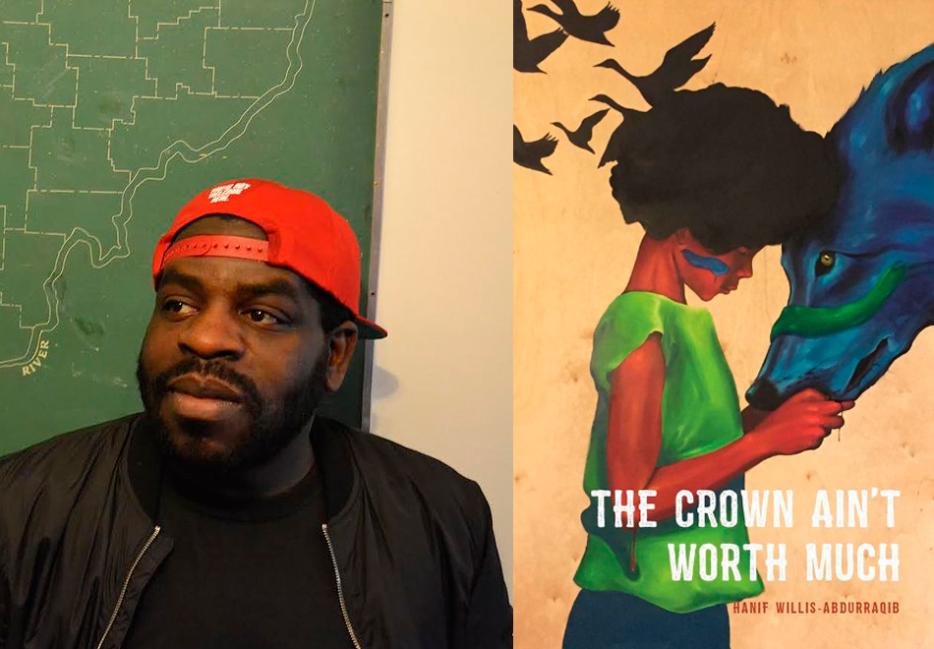

Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib is a punk rock bard from Columbus, Ohio (the east side, he specifies), who writes full-lung prose poems, reduxes of the classical ode, and updates and riffs on Frank O’Hara and Virginia Woolf. The Crown Ain’t Worth Much is his confident, vulnerable, slim but feisty debut. A columnist for MTV News, his interest in pop culture knits the collection together, with epigraphs as wide-ranging as Josephine Baker, Whitney Houston, Pete Wentz, and a CNN transcript of an interview between Nancy Grace and the parents of Michael Brown. I thought the collection’s title was a nod to the James Baldwin’s line: “your crown has been bought and paid for. All you must do is put it on,” but I stood corrected.

I spoke with Willis-Abdurraqib before the 2016 presidential election. In the dank fog of an America awaiting its next president-elect and parting with its first African American one, Willis-Abdurraqib’s collection has taken on a different insistence, and our conversation now feels tinged with something of the prophetic. In the hollow hours following the election results, he wrote “The Day After The Election I Did Not Go Outside.” The poem is peppered with ampersands—little swirling punctuation marks insisting on kinship, on affinity, on introspection when the world feels full of thoughtlessness. As an antidote to the murky times ahead, the poems of The Crown Ain’t Worth Much can be held in the palm of your hand like a string of prayer beads, taut in protest but with an unrelenting tenderness. Reading Willis-Abdurraqib is a balm, and, if ever the act of reading was in the service of self-care, I believe it is here and it is now.

Julia Cooper: You write for MTV as a columnist. Do you find it hard to jump between registers? Poets have traditionally been working men and women, because poetry doesn’t necessarily pay the bills, but do you find it hard to switch between the two forms?

Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib: Not really, I think a part of that is that MTV is so great at letting me write the way that I write, so they’re not trying to make me into a different writer than I am. In my prose and in my long form work I use poetic elements just because that’s the way I write, and they don’t try to strip that down.

Some of the poems in this collection feel like they had been brewing in your mind for a while. Was that the case? What’s your process like?

A lot of my writing process takes place in my head before it ever gets on paper. I think that I am someone who attempts to be thoughtful, but a lot of my thoughtfulness is driven by anxiety about my ideas and my ability to execute those ideas. If it feels like some of the poems had been brewing for a while, that’s the case entirely. I wait to commit things to paper. I know a lot of poets and writers are into running into the writing and then sorting it out later when everything is on the page, and I think that’s really admirable, but I don’t have the emotional capability or the confidence to do that outright. I need to take fully formed concepts, narratives, and ideas to the page, and that takes a lot of internal brewing.

Is the title a reference to Baldwin?

No, the title is a reference to The Wire, which is not Baldwin, but could be. I like The Wire a lot, and I was struggling for a book title really early on. The working title for the first draft of it was called The Greatest Generation, because I did not know there was a book already, like a huge book, like Tom Brokaw wrote it or something. I love the band The Wonder Years and they have an album called The Greatest Generation, and I thought this book spoke to that album a lot. And I was passing my book around and people would come back to me and say, “You can’t call your book this because there’s a really famous book called this,” and it came out in 2012 or something. And I was like, Well, shit.

So in The Wire one of the characters says: “The crown ain’t worth much if the nigga wearing it always getting his shit took.” I thought about it, and thought about what themes the book had rattling around it, like themes about displacement and gentrification, and the claiming of space— people having things taken from them that they held close.

I’m wondering, who else should I be reading? Who are some other young or lesser-known poets who you think deserve some due?

Nate Marshall is a poet from Chicago who I don’t think I could have finished this book without. I think his work is stunning and important and talks about place and home in a way that’s really great. Ariana Brown is a poet from Boston who is gifted. And I think Morgan Parker is really important; she’s right at the edge in pop culture and race and what it means to be a black woman in America in a way that’s stunning and brilliant.

I read that you look for poetry that deals in “the art of witnessing.” Do you think witnessing is always painful?

No, I don’t think so. I think that a big thing I’m trying to do now, especially with The Crown Ain’t Worth Much, is dealing with something that is really rooted in joy. I think the things that are most accessible to us are pain and grief, or fear. Like we can watch—we’re in a time where we can watch someone be murdered on a social media feed. While that is witnessing, witnessing is also sitting on a rooftop after a really good, long hard day and watching the sun go down. Or witnessing someone you love excel at something. I want to invest in that a little more, because I think once I detach myself from the pain of what I have witnessed, I need to find something to replenish myself. And I think finding joy to both witness and write about is really important.

I like this idea of investing in joy. I like that image. I was reading that you don’t have any formal training in poetry, which surprised me, but led me to wonder, is your love of music and therefore rhythm and cadence, is that what drew you to write poetry instead of prose?

I think so, yeah. The thing is—whenever I talk about how a lot of my peers have MFAs and really intense formal training, that is—I always wrote. I think often times, the narrative around the book is, “Oh, he didn’t go to school for poetry, so he just like stumbled into this, that’s wild.” But I wrote, I was writing music journalism, and I wrote in a very intense way that drew me close to language and the way words moved. Though poetry wasn’t natural, it was a reachable, touchable thing for me that I knew I could access and play out into something greater.

I was wondering if you found it hard to write publicly about some of your most intimate losses. Making yourself vulnerable—were you were worried about that? Was it cathartic?

It was hard, but I think not nearly as hard as grief without an outlet, grief with no map out of it. For me, although the poets I love write about sadness, their own sadness, very bluntly, they find a way to reckon with it and come out on the other side a lot cleaner, and happier, and freer. I think grief is work, in the same way that I think speaking about joy and trying to find joy is work. Grief sits on our bodies and works on us. And we don’t have to seek it out, it’s just there. So for me, the work of whittling it down is worthwhile. The work of writing about it, chipping away at it, and putting it out into the world where people can read it, and it can hopefully help people chip away at their own—I think that’s vital and important.

It was replenishing to read someone else’s grief so bluntly on the page.

I don’t want to talk about death all the time, I don’t want to revel in death, but at the same time, I’ve witnessed and suffered through a lot of deaths at a young age. What that did for me was make it real. It made death something that I understand as an inevitability, and it makes this brief, bright collection of hours that I have while living something that I am so thrilled about. Which doesn’t mean that I’m never unhappy because I’m so happy to be alive, but I have an understanding of death that won’t allow me to waste my time. I have an understanding of death that won’t allow me to be complacent and not give all of myself to the people I love and care about while we’re all still present. And I think that’s a real gift, and I think part of my writing about that in the book is not necessarily to bum people out, though I’m sure it happens occasionally, but to kind of say: I lived through this, and through that living I found an incredible clarity. I found this joy about understanding that I have limited time here, and I’m lucky that I have people who would miss me if I were not here anymore. I think the book is partly about that, about how I am trying to be better at loving and living and fighting for the things I believe in while I’m still present.