If you’ve never heard of Gary Hart, it’s because he was not the 40th president of the United States. Of the scandal that kept Hart from office so many decades ago, Matt Bai sums up his central conviction in All the Truth Is Out: The Week Politics Went Tabloid: “that what happened or didn’t happen with Donna Rice or any other woman was nobody’s goddamn business but his and his wife’s, and about as relevant to his qualifications for higher office as a birthmark or a missing tooth.”

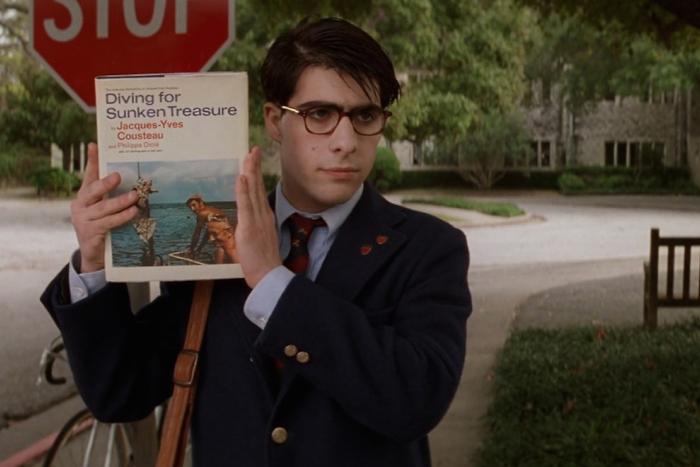

In 1987, as he campaigned for the Democratic nomination in the upcoming election, Hart was photographed with a woman who was not his wife next to a speedboat called Monkey Business. It was both the end of his political career and the beginning of a new era of political journalism in the United States. Before Hart, the private lives of people running for office were not seen as part of their candidacy; after Hart, private transgressions were seen as breaches of the public’s trust.

“Trust” is a key word in politics, a sort of magical metric that has little to do with a candidate’s policy positions and everything to do with what kind of person he or she seems to be. Obama seems nice, and much of our perception of his niceness comes from the strength of his marriage. The cognitive dissonance between the man who orders drone strikes on civilian targets and the man who makes a point of eating dinner with his family is too much for most voters to handle, and because dinnertime is something we understand, it tends to draw our focus.

The American perception that a person’s private life is the key to his or her value system means that infidelity is punished and marital bliss rewarded; it also has the consequence of excluding from higher office candidates who are seen to be transgressing social norms in surprisingly standard ways. Two categories in particular seem to be unacceptable to American voters: atheists and singles.

The US has had one bachelor president—James Buchanan, Jr., president from 1857 to 1861. Many speculated that he might have been gay, and maybe he was. What’s surprising is that some contemporary political commentators believe that the US has now come to view being single as a suspicious activity in its own right. In 2013, an article by Keli Goff in The Root was headed, “Could a Bachelor Win the Presidency?” Goff quotes political consultant Michael Goldman saying, “One day we will have an openly gay president. A gay president in a committed relationship will still be more comfortable for many people than someone who stays single.”

He explained, “It's always more difficult [for single candidates] because we tend to think that presidents who have families are more like us and share the same concerns about educating our kids, and so we feel more comfortable.” It’s an odd time for singles to be a distrusted social category. In 1960, 72 percent of Americans over 18 were married. But in 2011, the Pew Research Center found that this number is now barely half. A previous Pew study, conducted in 2010, showed four in ten Americans saying marriage was obsolete. More and more, single people are just as representative of the North American experience as married people.

The American perception that a person’s private life is the key to his or her value system means that infidelity is punished and marital bliss rewarded; it also has the consequence of excluding from higher office candidates who are seen to be transgressing social norms in surprisingly standard ways.

Similarly, it seems as though American voters living in a pluralistic society would be able to envision a president who does not conform to their religious beliefs. But polling consistently suggests that Americans see atheism as a reason not to vote for a candidate. A recent study by Central Michigan University psychologists Andrew Franks and Kyle Scherr compared attitudes towards black, gay, and atheist candidates, and found that Christian respondents were more likely to vote for a gay candidate than an atheist. Atheists were found to elicit a surprising range and strength of negative feeling: respondents felt distrust, disgust, and outright fear.

Personality is easier to understand than policy. It’s not surprising that voters often use qualities they have experience with—marital fidelity, religious conviction, devotion to one’s children—to predict how politicians will perform in situations they don’t. Whether we should or should not be conducting aerial bombing of Iraq is a multi-factor question, with both morally and logistically complex components.

But private life is complex too. Being married, as Hart can attest, is not necessarily a more stable situation than being single, and what Jesus would or wouldn’t do about most things is not at all self-evident. How a person behaves and how a government behaves may be analogous only in that neither is as easy to judge as we like to think.

Every week, Linda Besner reads a new book and writes on a tangentially related topic.