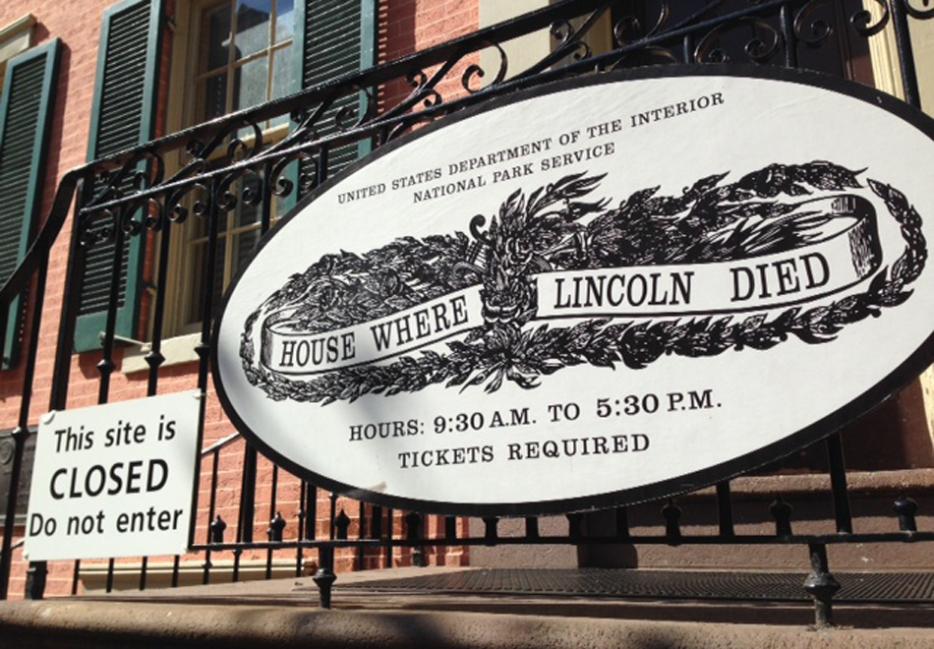

The government of the United States shut down this week, for the 18th time since 1976, sending 800,000 federal workers home without pay, shuttering national parks, and causing politicians to essentially announce to their citizens and the world that they can no longer run the country, which is pretty much the entirety of their job description.

If this week hasn’t made you proud to be a Canadian, it should. We often feel self-conscious about our government system when we compare it to the noble, Enlightenment-era checks and balances to the south, but it’s for some of those very reasons that such a complete shutdown couldn’t happen here.

The founding fathers made a fundamental mistake. They assumed, in their construction of their vaunted system of checks and balances, the existence of women and men of goodwill. I’m not sure if this was ever a reasonable assumption, but at the moment, in Western politics, it is not. And so we have, in the US, two unmovable forces butting heads and bringing the country to a halt over the desire of one party to discredit the other.

We don’t have checks and balances in Canada, and a complete shutdown over a budget dispute is not possible. Even when the government does dissolve, though, government workers still get paid, and the National Gallery remains open.

But something similar did happen in 1975 in Australia. You can read the details here, but the nub of it is this: When partisan bickering got in the way of a smoothly running government, Australia had a guy—a guy for whom there is not even a vague analog in the US—to step in above the partisan fray and fix things. We have one here, too, though he’s often considered the least significant guy in Ottawa, an embarrassment from a bygone era, a symbol of our fealty to our one-time colonial masters.

But the Governor General can get things done, and the fact that he hasn’t since 1926 is no reason to think he can’t. In fact, the GG’s long dormancy is a symptom of the very quality that makes the position so useful. The GG is like a great watchmaker. Our system’s all wound up and runs pretty well all by itself, and can continue to do so for decades, possibly even centuries. During that time, GGs come and go, drawing little curtains aside and nibbling bits of seal—people should be forgiven for thinking the guy’s caught in aspic.

The same goes for the Australian version. But then, in 1975, things went completely off the rails and the country entered the same red zone in which the US has now found itself twice in the last two decades. So GG John Kerr fired the prime minister and told the leader of the opposition to form a new government, which got the money flowing. Kerr then dissolved parliament, called an election that brought in the new guy with a majority, and then stepped back into the shadows.

Kerr died in 1991, but Sir Michael Hardie Boys, New Zealand’s GG from 1996 to 2001 and an outspoken analyst of the role of the vice regent in Commonwealth governments—he thinks Byng made the wrong choice with King, for instance—was kind enough to answer the phone when I called.

“I’ve always believed that the Governor General was right,” he says, speaking of Kerr, “because as I understand it, the prime minister was trying to run the country on a bank overdraft. … That’s contrary to the way things have to be and should be done.”

Contrary to the way things have to be and should be done. You may be able to think of a better précis of the US situation right now, but I can’t. And Sir Michael is convinced that the mere existence of a Governor General and his three reserve powers—to summon, prorogue, and dissolve parliament—brings with it a guarantee of orderly good government that is not possible in the US.

“I like to think of it as being like the razor strop my father used to keep in the cupboard,” he says. “He didn’t ever have to use it, but the fact that it was there was quite useful.”

It may sound paternalistic—it may in fact be the very definition of paternalism—but fathers do, from time to time, come in handy, and an unelected official with no partisan or even popular allegiance, who only uses his superpowers when all seems either lost or tipping over into nonsense, can sometimes be just the thing.

Professor David Schneiderman, a constitutional expert at the University of Toronto, thinks there’s actually much more to recommend the Canadian system than the Governor General, a position he thinks is essentially as decorative as it appears. He’s working on a book comparing Canada and the US on just these sorts of criteria, and calls our parliamentary system “more fluid, more flexible and more muscular” than the bicameral, triple-branch confection Adams, Franklin, Jefferson et al. came up with. He thinks, for instance, that parliament, even without the discredited senate, can take care of business, especially in a minority government—but in majority situations, too, with much greater amplitude than the US version. He also happens to think then-Governor General Michaëlle Jean did the right thing in 2008, when she granted a conditional prorogation of Parliament in the face of a potential Opposition coalition. In fact, the only weakness in our system as he sees it is the executive power of the prime minister, who can, if he wants to, do some pretty radical things (like declare war without consulting anybody).

But I was hooked on my watchmaker idea, so I started lobbing counterfactual scenarios at him. Schneiderman made it clear he’s a republican—he thinks the both the Governor General and the queen should be removed from the Canadian equation. But, given that they they’re still around for the time being, I asked, What if an especially choleric prime minister decided to wage war on Myanmar? “Well, let’s say Iran,” says Schneiderman, reeling me in. Though he has the ability to do it without conferring with anyone—”a hangover of the divine right of kings,” Schneiderman says—if the PM was completely off base, we could rely not only on the Opposition, but on a backbench revolt to put things right.

OK, I said, but what if, instead of just a whackjob PM, we had a whackjob majority government? It’s not beyond the pale—we had the Bloc Quebecois as the Official Opposition, you’ll recall, and the NDP under Layton came out of nowhere last time. What if a majority government decided to take back Alaska?

“Short of a constitutional problem,” he says, “or stepping on the toes of the provinces—and invading Alaska wouldn’t be that—and short of a Charter problem, which is hard to conceive in the circumstances; essentially, short of the intervention of the House of Commons, the executive branch has the authority to do that sort of thing. We have no real check, because we don’t have a divided government.”

So what then?

“Taking a leaf out of the colonial playbook, the Governor General could dissolve parliament and call an election.”

Unless the military itself revolted, it would in fact be the only play.

It’s an unlikely scenario. Nearly impossible, in fact. Sort of like Australia in 1975. But we’ve got that strop in the cupboard, just in case. Makes you wonder, if they had one in the US, whether the entire national government workforce would have been thrown out of work 18 times since 1976. As Sir Michael says, in tones of vice regal bemusement, “The situation suggests that someone like that’s needed, doesn’t it?”