There must be a ghostland somewhere where dead characters and stories live. Scenes, paragraphs, sentences, too, float like bodiless heads in the lower echelon of this land. Even words—bigger words that died for smaller words. The worst thing for a writer is to be precious about her writing. A writer has to be disciplined, try not confuse cleverness with quality. You have to kill and you have to kill swiftly—preferably without too much sentiment. That’s in theory. In practice, the reactions to those deaths vary and the ways of dealing with them vary too. Some deaths are permanent: a 150-page novel murdered, never to be seen again. Some metamorphose into new forms of life: a deleted scene in a book into a scene in a movie. Some deaths are resurrected, mutated—two characters becoming one. Here ten writers talk about dead characters, dead scenes and dead books and their ways of dealing with those deaths.

Andrew Pyper

There was a character in my novel The Guardians, named Scott, who was there for the first draft but got the axe and wasn’t there for the second. Both my editors, the Canadian and the British, suggested one of my (then five) main characters had to go, as it was too confusing to keep track of them. It was really hard, actually, because at that point I knew these guys, I’d written a whole novel with all of them there. But now I had to let one of them go. It was like Sophie’s Choice or something.

In the end I decided on Scott. He, along with the other four guys, had been inside the town’s “haunted house” in their teens when a terrible decision had been made on their part, and now they all harboured awful memories of what they’d seen, what they’d done, what they’d gotten away with. Of all the characters, Scott alone seemed to show no outward ill effects of this experience: moved to the city, a successful lawyer, wife and kids. He was normal where the other ones—all lonely, all a bit screwed up—weren’t. He was also the one who I at first saw as being the guy who falls under the spell of the house later in the book and does a terrible thing. I thought that would be surprising, because he seemed the most together. But then I saw how it would be even more surprising if someone else did the terrible thing because, in a way, don’t we always suspect the “normal guy” of not being normal?

So me and the rest of the characters got together and threw him overboard while he was sleeping.

Susan Glickman

The YA novel I’m working on now was abandoned twice before: the first time because my daughter became close friends with a girl whose older sister was severely handicapped just like the sister of the protagonist of my manuscript, and the second time because my revision of the story anticipated the plot of a hugely popular movie so much that people would have assumed that I copied it! Eventually I became close enough to my daughter’s friend, and her family, to tell them about my predicament, and they encouraged me to go ahead and write it. So I am.

Russell Smith

When I submitted my novel Girl Crazy to my editor at HarperCollins she said she wanted some scenes added to show how the sexy girl in the story appealed intellectually to the protagonist. So I wrote a new scene that had the couple going to a conceptual art gallery. I rather liked it. My editor read it and said, basically, meh, it was a nice idea but it isn’t working, forget it. It didn’t make it into the book. A couple of years later I was asked to write a screenplay adaptation of the novel and the producers asked a similar question – can we see that the girl is smart somehow? So I wrote a faithful adaptation of that cool art gallery scene. They didn’t like it either, and it is now missing from the film. So twice now I have written that failed scene. But I loved its atmosphere and meaning. I’m hoping to write it again somewhere else.

Susan Swan

In 2001, I had a female character named Win who was escorting her niece Luce through the Mediterranean in my novel What Casanova Told Me (published 2004). I was very attached to my description of her towhead—”as blond as hewn pine.” But that was the only interesting thing about her.

I can still remember the day I got the telephone call about Win not working. I put the phone down and staggered over to a chair. I felt like I was going to faint. I was breathing fast and thought I might throw up. But I knew my editor was right. Win was a bust from start to finish. And my editor helped me to see what I was already struggling with in the story although my loyalty to what I’d written kept me from admitting it. Once I had time to absorb the news on that terrible light-headed afternoon, I never looked back.

I tend to look at my characters as my children. But if I get too maternal it spoils my portrait of who they are. Some version of the mother/artist dichotomy. A writer can’t protect her characters; she needs to reveal them.

Catherine Bush

I lose point of view characters. For a long time, my forthcoming novel Accusation was told from the point of view of two characters, and the second character is still in the novel, but not as a point-of-view character. I often seem to start with POV characters that I don’t use, can’t use as POV characters. I’m interested in the side view, the oblique angle, but sometimes the side view is a stepping aside from the story’s heart, or is exploratory but not ultimately necessary. I just did a panel for the Guelph MFA program, four writers on structuring the novel and there were lost characters and jettisoned parts of novels everywhere. Why does it take so long to see what’s necessary? I think we have to be kind to ourselves re this process, the time it takes to live and re-see what the novel needs in order to find its life in turn.

Natalee Caple

I had a novel that was half written and researched—about 100-some-odd pages. I had gotten grants for it too. It was based on a case in New Mexico where a group of wealthy white kids kidnapped a busload of poor kids and buried the kids in a mine owned by the father of one of the rich kids. The case was the first major study done on post-traumatic stress in a whole community. I was really interested in the waves of guilt left over. In the real incident none of the kids died but the class issues were deep and the effect was profound.

It was substantially different from the Sweet Hereafter (the movie, the book) but the bus was such a big symbol and the idea of a whole community traumatized as the centre—it was too close. I felt my heart twist in my chest when I saw the trailer for the film. I tried reworking the project and then scrapped it. Ever since I have been haunted by the fear that another book will come out while I am still working on mine. I lived in so much fear of that while working on my new novel about Calamity Jane it was ridiculous. Joseph Boyden wrote a short story about a lost son of Calamity Jane that was published in the Walrus and I almost lost my mind! I contacted him to ask if it was part of a novel and he reassured me it was a one-ff but I imagine I sounded psychotic and possessive.

Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer

In my novel Perfecting, the character named Curtis was named Lucky in early drafts but then my dear friend had a baby and named him Lucky. What are the chances of that? Also, I’ve thrown out tons of scenes. I don’t feel bad about them. They are just the snapshots that don’t make it to the album. Writing is curatorial, in this way.

Angie Abdou

I recently cut a character from my work in progress because I realized she was announcing the book’s message. She was lecturing the reader—this is bad, this is good, this is what you’re supposed to think. I might have needed her in order to keep me on track while I was writing, but once the book is done, if I’ve done my work right, she belongs on the cutting room floor. A well-established writer friend told me that the one thing that gets easier about writing is the cutting. I figure if I act like it’s easy, eventually it will feel easy. So: snip, snip ... and she’s gone.

Nazneen Sheikh

When I wrote my cuisine memoir Tea and Pomegranates, I deliberately and suppose vengefully omitted a family member. In the midst of the galaxy of star-spangled cuisine stars of my family I removed the presence of an aunt who had been a childhood buddy. She was intellectually gifted and a great lover of books and poetry. When I was asked for a family album of pics for my memoir she refused outright. I was stunned this was my book-loving aunt and had contributed in her own way to my becoming an author. I deliberately left her out of a family group shot and wrote about all her siblings except her. I further compounded the crime by mailing the published copies to all her sibs except her. I knew the word would get out and I wanted to hurt her. This is a ghastly tale and in many ways I am ashamed of it. Did it matter to the book? Absolutely not, it garnered a medal from Cuisine Canada and was a runner up for IACP and had world rights sold to Germany. The Globe review was a dream as were others. I could not share all this with her.

When I write my books I fall in love with my characters and keeping this in mind I cannot kill what I love. I would not debase this gift which I have been given by resorting to vengeance... however having just written these lines I do acknowledge the fall from grace on this occasion.

Interestingly enough on my current writing trip I have met her on numerous occasions. We have never discussed this but somehow slipped into the ease of an old familial relationship.

Rebecca Rosenblum

I never consider a story or character failed—I consider it “in progress.” There are no stories I have given up on, just ones I haven’t worked on since 2007. Maybe it’s being a short story writer, it doesn’t take all that long to revise something once I know what I’m doing, so I always think I’m just months away from being able to rescue a story that’s a mess. Who knows, maybe this time I am? The story I’m thinking of, which is called Seven Lessons on Pedagogy, is one of my harlot stories—everyone’s had a go (at editing it). Back in the day (grad school), I received so many suggestions and so much different feedback that I no longer knew what the story was really about, so I put it aside. A few years later, it occurred to me that I knew, again, what the story meant and how it should go. But I didn’t go back and rewrite. Who knows why—busyness, laziness, lack of confidence. I’m pretty sure I will, someday and at that point, it’ll finally be what it never was, which is a good story. That’s my plan, anyway.

--

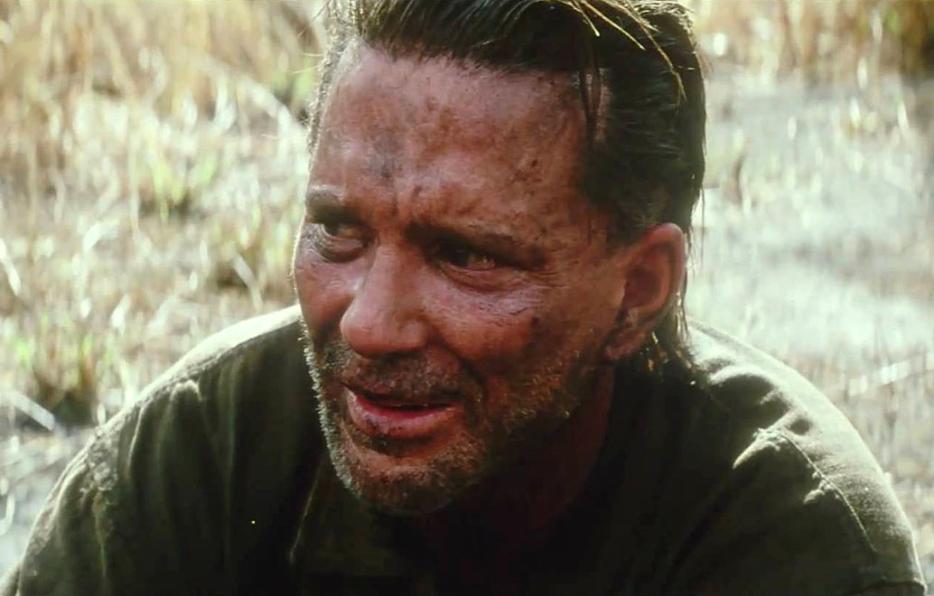

Image: Mickey Rourke, whose part in Terence Malick's Thin Red Line was cut in the final version. Which happens a lot to actors in Malick films.