My grandparents immigrated to Brazil from Montreal in the 1950s, and got involved in some weird business ventures (pineapple plantations; exporting a Brazilian soft drink called Guaraná) lucrative enough to allow them to employ household help. In her letters, my grandmother spills a lot of ink complaining about the help, all of whom, she says, are named Maria: “And all these Marias come in various shades ranging from coal black to just a touch of cream in the coffee, thanks.” My grandmother was writing these letters in the ‘50s and ‘60s, when white people said bullshit like that all the time. We like to think that nowadays, our ideas about race have evolved, and to some degree they have. But the significance of “various shades” in racial identification hasn’t gone away.

A forthcoming study in the journal Social Science Research by sociologists Stanley R. Bailey (University of California), Mara Loveman (University of Wisconsin), and Jeronimo O. Muniz (University of Minas Gerais in Brazil) examines how different census-taking methods change the picture of Brazil’s racial makeup. While most people think of race, the researchers note, as a static fact about a person—“a stable and unitary individual trait”—this isn’t how race actually behaves in society. Instead, “[r]acial identifications hinge on a constellation of factors, including self-perception, ascription by others, interactional cues, institutional contexts, and prevailing cultural understandings of consequential markers of human difference (Cornell and Hartmann, 1998; Jenkins, 1994; Harris and Sim, 2002; Roth, 2005; Brunsma, 2005; Daynes and Lee, 2008).” The researchers go on to say: “Since race is socially constructed, there is no a priori reason to assume that any given measure of race is more or less valid than others.”

To show how different views of race yield different answers about Brazil’s demographics, the researchers took data from the Brazilian Social Survey (PESB) from 2002; they used a sample of 2330 people in 102 municipalities (because their study was concerned with white, brown, and black categories, they took out respondents who classified themselves as Asian or indigenous). The researchers then made a series of pie charts to show how racial breakdown in Brazil changed when six different ways of gathering or categorizing data were used:

1) Census: the traditional method in the Brazilian census has been to ask people to self-classify as black, brown, or white.

2) Ascribed census: with this method, it’s the interviewer who classifies the respondent as black, brown, or white.

3) Post-hoc binary: the respondent has already answered the census question asking them to describe themselves according to one of the three racial categories. Now, people analyzing the data eliminate the “brown” category and define everyone who answered “brown” as “black.”

4) Descent rule: this is about what race your parents are. Respondents are told to call themselves “white” if both parents are white, but “black” if at least one parent is black or brown.

5) Forced racial binary: respondents have already answered a question about whether they consider themselves white, brown, or black; now they are asked to choose between calling themselves “black” or calling themselves “white.”

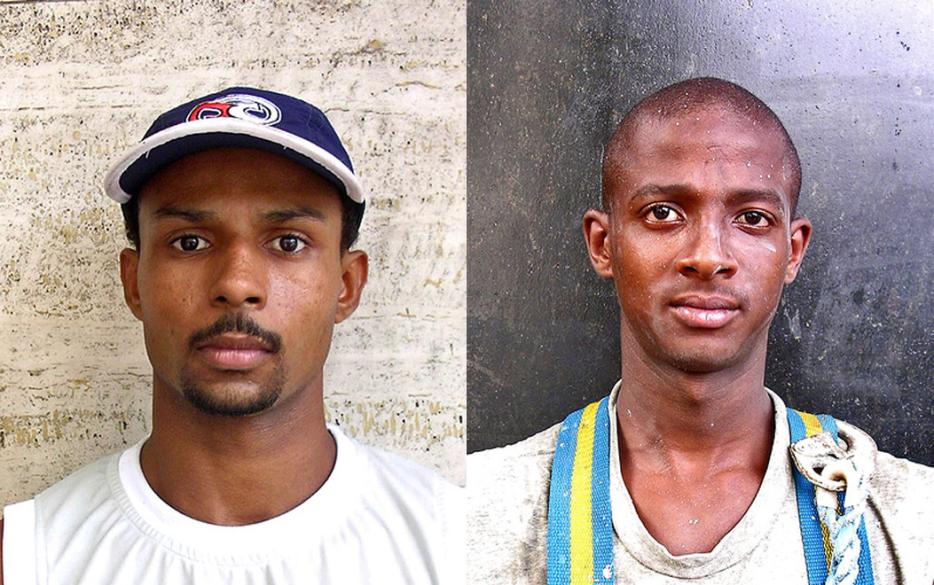

6) Photo comparison: this is an interesting one. Respondents are shown pictures of eight people with different skin tones, and asked a) to say which ones they would call “white” and which ones “black”; and b) which of the people pictured has a skin tone that most resembles the respondent’s own.

As you can imagine, these different ways of asking about race produced wildly different pictures of what Brazil looks like. Here are a few highlights: when race is judged by the “forced racial binary” (respondents have to decide whether to call themselves white or black), Brazil seemed to have a 70 percent white population. When researchers applied the “descent rule,” similar to the US slavery-era law where “one drop of blood” was enough to classify someone as “Negro,” Brazil’s population was about 40 percent white. Then there’s how respondents perceived their race versus how someone looking at them perceived it: the overlap between self-reported and ascribed race came in at about 75 percent. So a quarter of the time, someone looking at you has a different perception of your race than you do (this was especially the case when interviewers decided someone wasn’t white).

The researchers also cross-referenced the racial data with some economic data about income. They found that the wage gap between white and non-white respondents got worse as respondents advanced up the income scale—essentially, in the top 10-20 percent of the income structure, people who aren’t seen as white get paid significantly less than people who are. And the darker your skin tone is, the more pronounced this effect. The researchers note that this mirrors findings from US surveys.

The upshot of all this, the researchers say, is that, for one thing, we should ask a lot of questions and a lot of different kinds of questions when we’re trying to figure out what race means in a society. Since race is kind of a made-up thing, but with extremely real and serious consequences, getting a better handle on who’s making up what categories in which situations may help us figure out how to effect change. For example: “If a racial gap in educational achievement outcomes is larger when race is defined by survey interviewers than it is when race is self-defined, this could steer analytical attention toward theories focused on the role of ascription and discrimination in educational outcomes, as opposed to theories focused on self-esteem or identity.”

It’s ironic, really, that my grandmother was so cavalier in her racial prejudices towards the other women working in her house. My grandparents were Jewish, and when they were growing up, “Hebrew” was still a racial category on the Canadian census, and “looking Jewish” enough to bar you from some employment. She and the Marias become more or less alike, depending on how you ask the questions.