By the time I arrived at Toronto’s International Antiquarian Book Fair I’d missed all the smut. It was noon on the fair’s last day, Sunday, and I’d given myself an hour to awkwardly schlep around on my lonesome. The trade show, held at the Metro Toronto Convention Centre, is put on annually by the Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of Canada, an organization that accredits dealers in papers of antiquity and strives to protect the ravenous for rare books public from shucksterism. There were a few marvels, and many old—and in a few cases borderline ancient—artifacts exhibited on ad hoc shelves and behind glass. The smut, which I was too late to witness, came printed and bound, of course—not as live performance. More anon.

There was, however a first edition of Mrs. Dalloway, alongside a few other Hogarth wonders. And a striking cloth bound first edition of John Maynard Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. I can’t stress enough just how exciting it was to see this 1936 volume, with its cumbersome title, though I will confess that I couldn’t muster anything more than even slightly passing interest until I saw its asking price: $10,800. Or, more truthfully, $10,815, if you count the cost of admission to the show. I realized that I was looking at art, or some other very fine thing. Certainly something out of my conceptual and financial reach.

When I told Jason Dickson, a director of the ABCA, that it was my first time visiting the fair, he asked me what my impressions were and if I was enjoying myself. I was honest, and said “not really.” He laughed, good-naturedly. “Just like the rest of the books industry,” he said, “we’re in the middle of a generational shift.”

The Internet has vastly altered the way that all booksellers do business, and while the market for rare and specialist books is growing, retail and roadshows may not be the best bet for the future of the trade. I mentioned Jason Rovito, of Paper Books, and his experimental digital journal made from fragmentary photographs of his catalog. “Jason’s a very forward thinking bookseller, and I’m always trying to recruit him to the ABAC,” Dickson said, adding that he’d like to see these sorts of materials outside of strictly retail environments. “I want to go to places closer to the kinds of places I personally frequent. Like, say, art galleries.” He mentioned Stephen Fowler, of Toronto’s beloved The Monkey’s Paw, as another forward-thinking antiquarian. It was Fowler’s first time exhibiting at the fair, and Dickson suggested we might like to compare notes.

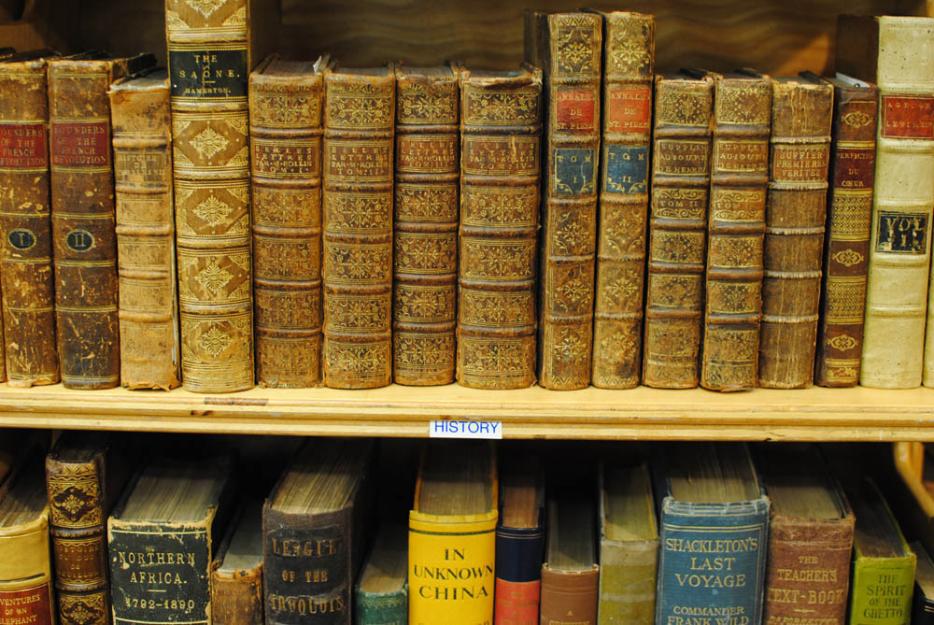

Fowler had a series of beautiful books and pamphlets on display. He was sad to say he had just sold out of his vintage gay smut. “See that woman over there?” He indicated a grey haired woman in an austere black turtleneck leaning over a glass case containing a Spanish monk’s ornate manuscript from the 15th century. “She’s a library director and she just bought up all my smut. Sex sells!”

When I asked him if it was worth it to come to the fair, Fowler said he hadn’t yet decided. His shop does a modestly brisk business, and as was proving the case at the fair, the choicer, more titillating items practically sell themselves. He had rather hoped to place some of his more expensive items into a collection. “I think mostly about selling to people, to customers who come into the store,” he told me, “so it’s been nice to be here and meet with people representing institutions, looking to acquire for their collections. Law libraries, for example, already have all the important first editions. So it’s good that I have all these hand pamphlets for them to look at. They’re buying up that kind of ephemera.”

He told me that the $1,500 tabling fee seemed excessively punishing, and that unless he unloaded his big ticket items it might not have been worth it in the end. I told him that he had paid 100 times what I had to be there, and he laughed. He mentioned some vague plans for the ABAC, having just been appointed to the board that morning. But then he surprised me, “A bookseller might just tell you anything,” he said, “out of loneliness.”