Gather a group of bookish folk around a table one evening and, almost without fail, the idea that “screens are inherently distracting” will soon spill out. In my experience, it’s usually the second glass of wine that does it—unless of course these folk are from publishing or academia, in which case, after a failed attempt to not think about work, they’ll start the discussion after drink number four.

Even in that tipsy state though, the feeling that tech is bad for attention is not only spurred by our anecdotal experience of iPhones and the like, but also a lingering wonder at how our brains react to the nature of different forms. Digital tech seems impermanent and fickle: dependent upon electricity and seemingly not “there” in the way print is. We assume that the ability to flick away from reading a book to playing a game on the same device makes the medium less engaging than ink and paper.

Yet, though there are provocative questions to be posed about “the inherent nature of the screen,” there’s another that needs to be asked, too: what might a digital form built from the ground up to encourage attention look like? One such answer might be Tapestry, a new app that allows you to build something called “tap essays”: short pieces of writing that are broken up into individual screens, and that require you to tap the screen of your phone or tablet to read the next word, sentence or page.

The idea stemmed from the work of “media inventor” and author Robin Sloan, whose “Fish“ was not only the first tap essay, but itself a meditation on focus and permanence in digital media. Sloan contributes one of Tapestry’s first entries, “Italics,” in which he, having recently seen some of the very first bound books printed by Aldus Manutius, ponders what it might be like to create something as lasting as italic type itself.

What’s interesting about Tapestry, beyond the pieces it hosts, is what you might call its “grammar of attention.” An author can choose how to present her work in a manner specific to the nature of screens, by highlighting certain phrases in unique ways, whether deliberately revealing one word per tap, forcing the reader to slow down, or suddenly changing the background colour to reframe what is being read. Jonathan Minard repurposes Adrienne Rich’s poem “After Sappho,” which meditates upon the sublime, almost inarticulable nature of desire. Minard changes the size of text to differently inflect a phrase, occasionally makes the screen go black, or places a word against an image of the Milky Way, intimating the vast blankness of the galaxies the poem uses to conjure the suprahuman infinite.

Because our attention is finite, there’s something very intriguing about a digital form that, in its structure, acts like poetry. It asks you to pay attention to each word, and also to the way each word is presented. The cadence and rhythm of sentences has always been a meeting point between reader and writer, but here it acquires another, altogether more tactile dimension, each crucial point punctuated by the tapping of your own finger.

It’s true that of the few first tap essays, not all are profound. But even Patrick Moberg’s “Lessons from a Dog,” which trots out some well-worn life lessons from our canine friends, still works well within the format, and what might be trite elsewhere has a certain charm when paced in this way.

Betworks, the company behind Tapestry (and sites like Digg) hopes that, if Tapestry takes off, it could become a platform for popular tap essays. I’m not sure that’s what will happen; it seems that the app is more a thought experiment put into practice. That’s not to say it’s not a fascinating one—simply that it speaks to what is currently a niche market of people seeking new forms of writing and expression using digital technology.

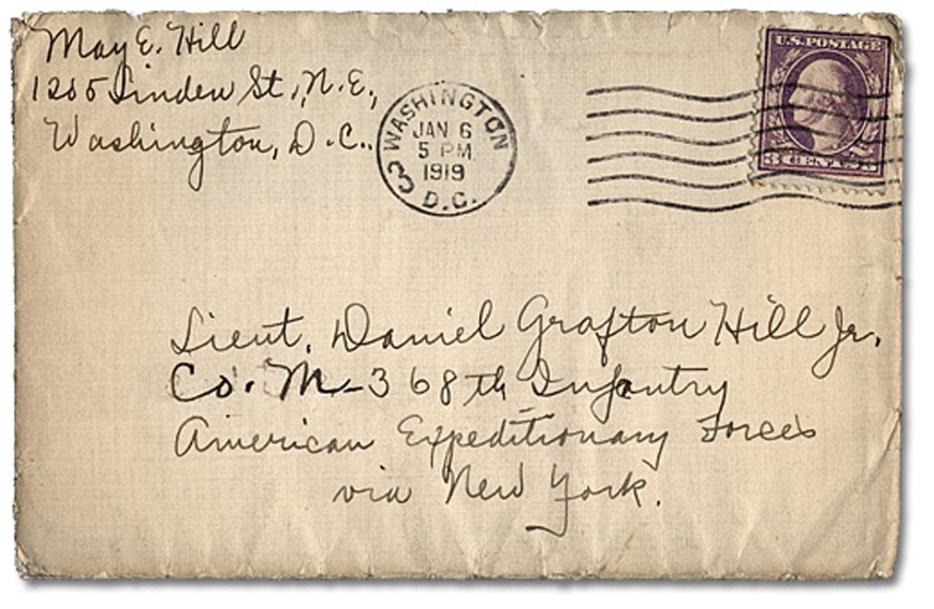

What did strike me while perusing these writings was that the careful affection of the tap essay may be better suited to another form entirely: the letter. When we write to those we love, we are most desperate for the reader to slow down and pay attention, and to understand what we said in the way that we meant it. It’s a comforting thought, too: that when we design digital tools to focus on meaning rather than “content,” they become more than another wave in the technological flood, and instead help us reclaim what in writing is most human.

--

Photo by 1000awesomethings