"I just hate terrorist attacks,” the thin nurse says to the older one. “Want some gum?”

The older nurse takes a piece and nods. “What can you do?” she says. “I also hate emergencies.”

“It’s not the emergencies,” the thin one insists. “I have no problem with accidents and things. It’s the terrorist attacks, I’m telling you. They put a damper on everything.”

Sitting on the bench outside the maternity ward, I think to myself, She’s got a point. I got here just an hour ago, all excited, with my wife and a neat-freak taxi driver who, when my wife’s water broke, was afraid it would ruin his upholstery. And now I’m sitting in the hallway, feeling glum, waiting for the staff to come back from the ER. Everyone but the two nurses has gone to help treat the people injured in the attack. My wife’s contractions have slowed down, too. Probably even the baby feels this whole getting-born thing isn’t that urgent anymore. As I’m on my way to the cafeteria, a few of the injured roll past on squeaking gurneys. In the taxi on the way to the hospital, my wife was screaming like a madwoman, but all these people are quiet.

“Are you Etgar Keret?” a guy wearing a checked shirt asks me. “The writer?” I nod reluctantly. “Well, what do you know?” he says, pulling a tiny tape recorder out of his bag. “Where were you when it happened?” he asks. When I hesitate for a second, he says in a show of empathy: “Take your time. Don’t feel pressured. You’ve been through a trauma.”

“I wasn’t in the attack,” I explain. “I just happen to be here today. My wife’s giving birth.”

“Oh,” he says, not trying to hide his disappointment, and presses the stop button on his tape recorder.“Mazal tov.” Now he sits down next to me and lights himself a cigarette.

“Maybe you should try talking to someone else,” I suggest as an attempt to get the Lucky Strike smoke out of my face. “A minute ago, I saw them take two people into neurology.”

“Russians,” he says with a sigh, “don’t know a word of Hebrew. Besides, they don’t let you into neurology anyway. This is my seventh attack in this hospital, and I know all their shtick by now.” We sit there a minute without talking. He’s about ten years younger than I am but starting to go bald. When he catches me looking at him, he smiles and says, “Too bad you weren’t there. A reaction from a writer would’ve been good for my article. Someone original, someone with a little vision. After every attack, I always get the same reactions: ‘Suddenly I heard a boom,’ ‘I don’t know what happened,’ ‘Everything was covered in blood.’ How much of that can you take?”

“It’s not their fault,” I say. “It’s just that the attacks are always the same. What kind of original thing can you say about an explosion and senseless death?”

“Beats me,” he says with a shrug. “You’re the writer.”

Some people in white jackets are starting to come back from the ER on their way to the maternity ward. “You’re from Tel Aviv,” the reporter says to me, “so why’d you come all the way to this dump to give birth?”

“We wanted a natural birth. Their department here—”

“Natural?” he interrupts, sniggering. “What’s natural about a midget with a cable hanging from his belly button popping out of your wife’s vagina?” I don’t even try to respond. “I told my wife,” he continues, “‘If you ever give birth, only by Caesarean section, like in America. I don’t want some baby stretching you out of shape for me.’ Nowadays, it’s only in primitive countries like this that women give birth like animals. Yallah, I’m going to work.” Starting to get up, he tries one more time. “Maybe you have something to say about the attack anyway?” he asks. “Did it change anything for you? Like what you’re going to name the baby or something, I don’t know.” I smile apologetically. “Never mind,” he says with a wink. “I hope it goes easy, man.”

Six hours later, a midget with a cable hanging from his belly button comes popping out of my wife’s vagina and immediately starts to cry. I try to calm him down, to convince him that there’s nothing to worry about. That by the time he grows up, everything here in the Middle East will be settled: peace will come, there won’t be any more terrorist attacks, and even if once in a blue moon there is one, there will always be someone original, someone with a little vision, around to describe it perfectly. He quiets down and then considers his next move. He’s supposed to be naive—seeing as how he’s a newborn—but even he doesn’t buy it, and after a second’s hesitation and a small hiccup, he goes back to crying.

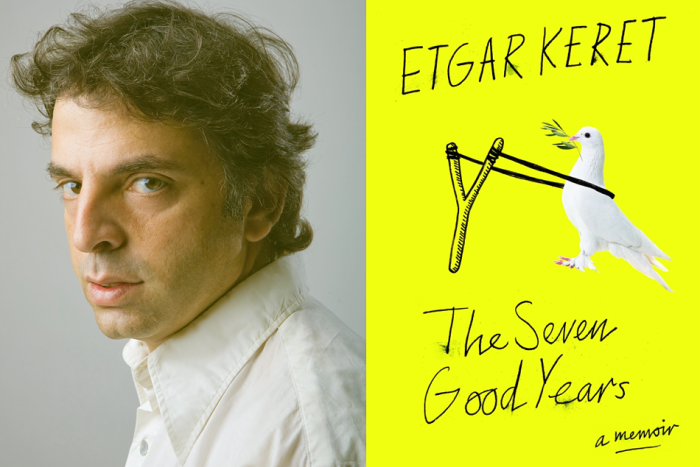

Read Etgar Keret's The Seven Good Years.