My grandmother dated a lot. This wasn’t out of some essential wantonness or a particular desire to play the field: it was a matter of circumstance. If you were the only available woman where you lived, you’d get asked out a lot, too.

In 1921, Toronto had 1,947 Chinese men and just 88 women. That ratio became even more skewed after the Exclusion Act, a piece of legislation inspired by fear of the “Yellow Peril” that banned all Chinese immigrants from the country. By the time my grandmother snuck through in 1937, using her cultural visa as an opera singer to escape her home country after Japan sacked Nanjing, she was one of a just handful of Chinese women of marrying age in the city. My grandfather—a nice guy with strong English skills and good prospects—got lucky.

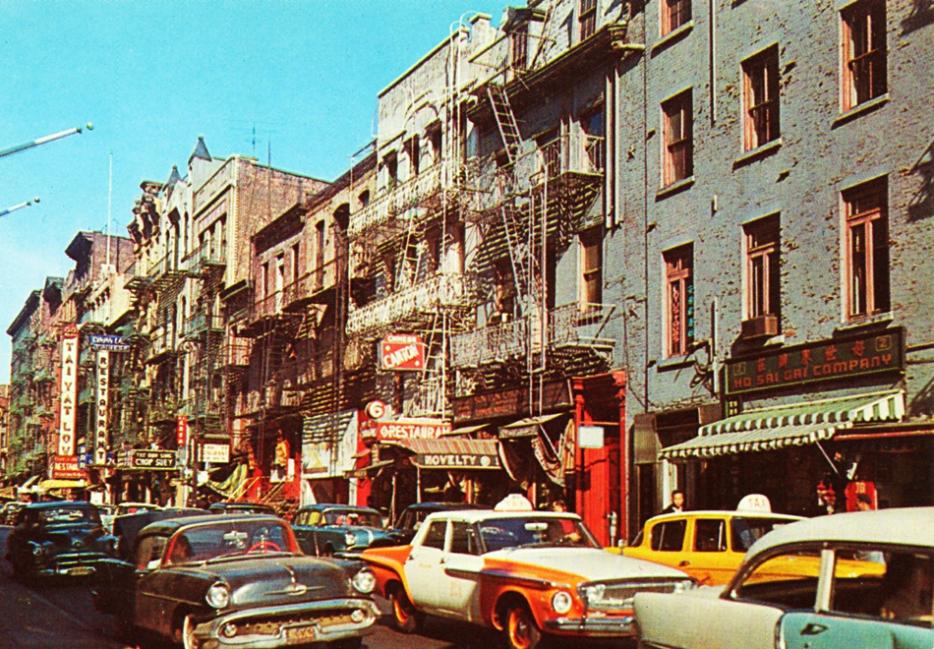

For most other men, mid-century Chinatowns across the continent were lonely places. Many male workers who had come to the west with the hopes of eventually bringing their families overseas were stranded. Across North America, the sight of a Chinese woman was cause for wonder. The skewed sex ratio created “bachelor societies”—neighbourhoods of grown men living together, sleeping in bunk beds, playing mahjong, and sharing the companionship and responsibilities that are usually dispersed across a family unit.

The Chinatown bachelor societies were inadvertent social experiments—strange, often unhappy places—but they were limited to a small portion of the population. In the years to come, however, we’re set to see a similar experiment—except on a much larger, more dangerous scale.

Many people have written about the effects of the one-child policy on Chinese demographics. For a variety of reasons—filial piety, tradition, the fact that sons are expected to support their parents, simple misogyny—Chinese society holds a strong preference for sons. When technology making sex-selective abortions became more readily available, many couples with just one chance at parenthood did everything in their power to make sure that kid was a son.

China’s unbalanced sex ratio has existed for years. Now, though, as that generation’s first group of men reach marrying age, we’re about to see the results. A recent study by Catherine Tucker and Jennifer Van Hook in Population and Development Review attempts to assess the seriousness of the problem. Gender imbalance at birth, after all, isn’t identical to imbalance at marriage. Men tend to have a higher mortality rate, and there’s usually an age gap between husbands and wives.

Examining the figures, however, Tucker and Van Hook come up with some scary predictions.

By 2030, they estimate, a full 25 percent of the male population will be single—a bachelor society of 30 million men. And even if sex-selective abortions stop tomorrow and the male-female ratios level out, it will take until 2050 for the percentage of single men to drop below 10 percent. What that kind of world looks like is hard to imagine. The authors muse about an increase in commercial sex, a rise in HIV/AIDS, widespread poverty, higher levels of criminality and violence. Certainly the loneliness and depression that marked the lives of many of the men living in North America’s bachelor societies will be reproduced on a vast, national scale.

But while the demographic future of the country is grim, there are some faint signs that things are improving. In a study published in The China Journal this month, Sung Won Kim and Vanessa L. Fong look at the way gender attitudes have changed in China. Fong and Kim analyzed surveys of people brought up under the one-child policy in Dalian, a large coastal city in northeastern China. Respondents were interviewed twice, once in 1999 and then again between 2011 and 2013, and asked whether they thought it was better to have a daughter than a son.

In 1999, when the interviewees were teenagers, 27 percent of males expressed a preference for a son. By 2012, however, their answers had changed, with 14 percent of males hoping for a daughter, 11 percent hoping for a son, and the vast majority indifferent.

The change indicates the degree to which gender equality has increased since the one-child policy was instituted in 1979. Girls have found educational opportunities that previously would have been denied to them, and urban families have come to value daughters, relying on their ability to provide support in China’s new economy. More than that, the authors argue that same one-child policy that created the glut of single men may have also made daughters more desirable. Without the ability to divert resources to sons—putting a son through school while a daughter labours—families have invested all of their resources in their single child, male or female. “Out of necessity many parents of daughters came to embrace the idea that daughters were just as good as sons,” the authors write.

Though just one small study, Kim and Fong’s work helps show the wrongheadedness of thinking about “traditional” beliefs as immutable cultural truths. A preference for sons can be a long-standing, deeply ingrained practice, but traditions change with circumstance. A society with equal opportunities for men or women is a society in which son-preference quickly diminishes. This good news comes too late for the current generation of single men, but it’s a hopeful sign that the coming bachelor societies will be much like the last: haphazard communities that grew out of a misguided government policy, then disappeared forever.