Last summer, as NSA surveillance revelations reverberated across North America and around the world, another U.S. government data-gathering initiative was making headlines throughout Europe. After five years of steadily escalating legal action, the United States’ Internal Revenue Service and Department of Justice launched a two-pronged attack to decisively put an end to the centuries-old tradition of Swiss banking secrecy, collecting thousands of client names and engaging in aggressive one-on-one negotiations with firms they suspected of holding untaxed U.S. assets. And while the actions have extended to other alleged tax havens, such as the Caribbean, Singapore, India, and beyond, the famous Swiss banking system has been the highest-profile target.

Two major international Canadian banks may be affected in the sweep: Royal Bank of Canada, which, as the sixth-largest wealth manager in the world, has a Swiss wealth management branch based in Geneva whose website has publicly announced that it is considering participating in the Department of Justice’s “non-prosecution program”; and the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, which the Department of Justice served with a “John Doe” summons last April, seeking U.S. client information from its Caribbean subsidiary.

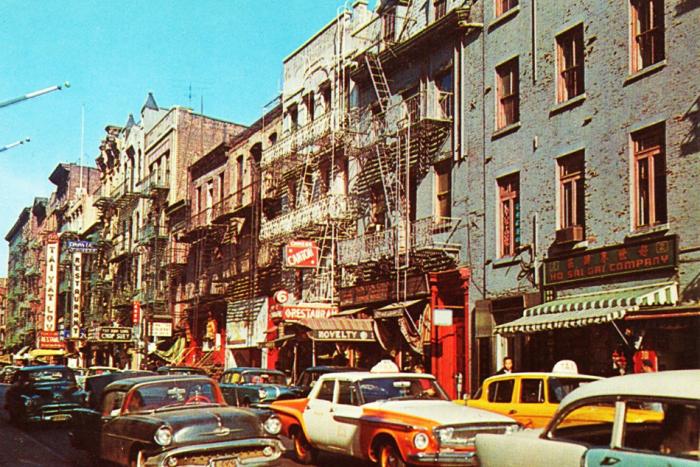

Switzerland’s status as a haven for foreign money dates to at least the eighteenth century, when European aristocrats, fearing the upheaval of a war-torn, revolution-prone continent, sought safe harbor for their wealth in the famously neutral and stable Alpine nation. The secrecy policy was codified in the 1934 Federal Act on Banks and Savings Banks, which until recently made it a crime to disclose account holders’ names. The policy has made Switzerland a magnet for international wealth; according to the Swiss Bankers’ Association, there is approximately US$2.2-trillion worth of foreign assets under management by Swiss banks.

Less well-known, however, is that today, many “Swiss banks” are not even Swiss: foreign banks are free to avail themselves of the country’s banking secrecy laws, and most major global financial institutions have wealth management branches in Switzerland. The same could be said for other jurisdictions around the world with strong bank secrecy laws—not just the aforementioned Singapore and parts of the Caribbean, but U.S. states like Delaware, too. While some argue bank secrecy policies allow wealthy individuals and firms to protect their wealth against the threat of political or economic instability, others say it’s just a trick to let them shelter it from taxation. Either way, the wealth management industry relies heavily on these locations.

This ever-widening net has swept up several other banks, including the Swiss subsidiary of banking giant HSBC, which gave U.S. authorities the names of 1,500 of its own employees. “Now these 1,500 people have to wonder whether they can travel to the U.S. or elsewhere because they’re afraid they will be arrested if they’ve been put on the INTERPOL list,” says Hornung. This fear is well-founded: on October 19, former UBS executive Raoul Weil was arrested in Italy on charges brought by the United States back in 2008.

At least, it did. The non-prosecution program, which the Department of Justice announced in partnership with the Swiss government on August 29 of last year, ”encourages” Swiss banks with U.S. clients to cooperate fully with American legal authorities in order to avoid criminal charges. Those who do will agree to pay substantial financial penalties of up to hundreds of millions of dollars, disclose all cross-border activities and accounts in which U.S. taxpayers have a direct or indirect interest, provide information on other banks that transferred or accepted funds from secret accounts, and close the accounts of non-compliant U.S. taxpayers. This action came after Swiss legislators rejected a series of attempts to establish a formal treaty or legislative solution through the nation’s parliament and executive branch. Now, Swiss banks are being pressured by their own government to negotiate directly with the United States without intermediaries.

“It’s against any international agreements, it’s against the basic international concept of equality between sovereign states,” says Douglas Hornung, a Geneva-based financial lawyer. “The U.S. has a huge ability to impose their own rules and their own laws, and that’s what they’ve proceeded to do against Switzerland and Swiss banks.”

The Justice Department instituted the non-prosecution program to allow banks to escape indictment for facilitating tax evasion by voluntarily placing themselves in one of four categories by the end of 2013. There is now a long list of banks that have elected to participate in the program, though not all participants have announced it publicly. The program’s first category is for banks that were in discussions with the Department of Justice before August’s announcement, many of which are already disclosing information to reach individual settlements; the second is for those ready to admit to violating U.S. laws and start making a deal; the third is for institutions whose U.S. clients’ assets are all already declared with the IRS; and the fourth is for those whose operations are solely local.

For banks caught in the first two categories, the penalties may be severe: “There will be payments, in large sums, from the banks to the Justice Department, in return that they will get non-target or non-prosecution agreements,” says Martin Naville, CEO of the Swiss-American Chamber of Commerce. “For the Swiss financial markets, it’s the beginning of a big cleanup. The business with any kind of undeclared money is over.”

The United States’ ability to impose its laws abroad derives from its central role in international finance. The Department of Justice can exert huge amounts of pressure on a targeted financial institution just by threatening to open a grand jury criminal investigation. If that happened, “the first measure the U.S. could take would be preventing them from having any business or any operations in U.S. dollars,” says Hornung. “Since the U.S. dollar is one of the most common currencies used by the banks, it would be very difficult for these banks to survive.”

Naville agrees: “It’s such an enormous market, you have to be in it … so we have to accept their rules.” Thanks to this power, the Department of Justice has been able to impose the terms of its non-prosecution program on all banks suspected of having untaxed U.S. assets.

The penalties are vastly preferable to the consequences of non-compliance, says Rob McKenzie, a tax lawyer and partner at Chicago-based law firm Arnstein & Lehr. Take the case of Wegelin & Co., Switzerland’s oldest bank, which announced early last year that it would have to close following a guilty plea to the Department of Justice. Wegelin refused to negotiate with the IRS at first, arguing that the service didn’t have jurisdiction due to the fact that the bank had no U.S. branches. The IRS responded by indicting Wegelin and confiscating all the money in a separate bank it worked through in the United States, after which Wegelin pleaded guilty to helping Americans hide their money.

This ongoing campaign is the culmination of years of steady work by the Justice Department, which has used its leverage to compel the largest banks in Switzerland—UBS, Credit Suisse, Julius Baer—to hand over tens of thousands of client and employee names. According to Hornung, the current crackdown originated in 2008, when Bradley Birkenfeld, a private banker at UBS, discovered that the IRS was about to indict him for assisting a wealthy California-based real estate developer named Igor Olenikoff evade taxes.

“So he decided to cooperate,” explains Hornung. “And that’s how the IRS and the Department of Justice built up a very specific file against UBS. And in February 2009, they gave an ultimatum to UBS, saying either you give us the names and details of your clients or we indict you.” UBS subsequently paid a $780-million fine and handed over 4,450 U.S. client names. The bank was also forced to disclose the names of any banks to which their U.S. clients had moved their money when they left UBS after the case had become public.

This ever-widening net has swept up several other banks, including the Swiss subsidiary of banking giant HSBC, which gave U.S. authorities the names of 1,500 of its own employees. “Now these 1,500 people have to wonder whether they can travel to the U.S. or elsewhere because they’re afraid they will be arrested if they’ve been put on the INTERPOL list,” says Hornung. This fear is well-founded: on October 19, former UBS executive Raoul Weil was arrested in Italy on charges brought by the United States back in 2008.

The IRS has also assembled a database of over 40,000 Americans who have voluntarily come forward and disclosed through the IRS’s Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program, which began in 2009 and has steadily increased the punitiveness of its fines through subsequent renewals in 2011 and 2012. “Every one of my clients who comes in has to tell them the name of the bank, where they have their money, how much money is there, the names of the bankers who assisted them, the names of any other financial advisors that assisted,” says McKenzie.

Once the Department of Justice announced its intention to serve Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce a “John Doe” summons seeking the identities of “U.S. taxpayers who may hold off-shore accounts” at CIBC’s First Caribbean Bank, McKenzie speculated the action could lead to a grand jury investigation—otherwise, he says, why issue the summons? If he’s correct, he says, the bank “will have to enter into an accommodation with the IRS similar to the UBS agreement or face the result of Wegelin.”

“We have 300 banks in Switzerland, among them of course many foreign banks, like the Canadian banks,” says Hornung. “And these banks’ business model was to sell the bank secrecy laws. It’s very difficult for them to change their business model. Why would a Canadian open a bank account in Switzerland if there are no more bank secrecy laws?”

For its part, Royal Bank of Canada’s Geneva branch is publicly displaying its efforts to ensure compliance with U.S. tax law. On the front page of Royal Bank of Canada’s Geneva branch website is a section called “USA-Switzerland Non-Prosecution Program.” It presents two documents requesting American clients to register their accounts with the IRS, and announcing a waiver of any bank secrecy expectations. According to McKenzie, “the banks that are not under the threat of a grand jury have not posted [their involvement] that aggressively. They’ve been sending letters to their customers saying ‘it’s in your best interest because of FATCA to come into the IRS program and disclose,’ and they then give details on the IRS disclosure program.” In McKenzie’s view, “RBC is considering making a deal with Justice before it becomes subject to a grand jury investigation.” If that were the case, he says, RBC would be among the banks required to disclose their clients within one year and pay a per capita penalty for each client that hadn’t entered the IRS’s Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program during that period.

When reached for comment by email, Royal Bank of Canada responded with a link to a description of the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act from the Canadian Bankers’ Association website, and did not respond to follow-up questions. When contacted by phone, a representative, Laurence De La Garde, provided her email and asked that questions be sent there. When asked if the bank intended to participate in the Non-Prosecution Program, though, she declined to comment.

So, what impact will this new global tax compliance regime have on the Swiss and other foreign subsidiaries of Canadian banks? It depends on how one views the wealth management industry itself. Martin Naville was positive about the future, insisting that foreign wealth management businesses based in Switzerland have “nothing to do with not paying taxes. It’s just for when you want to have part of your money managed in another place—a place that has a lot of experience with international investments and international currencies and languages. And so I think those branches have a very good strategic business role for [Canadian] banks.” Regarding U.S. tax compliance, Naville says, “any subsidiary needs to clean up their legacy, and then they could have a very good role in Switzerland. It is the place where wealth management will continue to be done, institutional and private. If you want to be an international bank, this is a good place to have a subsidiary.”

Some, however, think it’s unavoidable that the crackdown will cause many of these branches to shut down. “We have 300 banks in Switzerland, among them of course many foreign banks, like the Canadian banks,” says Hornung. “And these banks’ business model was to sell the bank secrecy laws. It’s very difficult for them to change their business model. Why would a Canadian open a bank account in Switzerland if there are no more bank secrecy laws?”

Others still think that Swiss-based banks will simply seek clients elsewhere.“Wealth management is very important for Switzerland, especially the management of non-declared money, of tax fraud money,” says Sébastien Guex, professor at the University of Lausanne and an expert on the history of Swiss banking. “That has been the very basis of the Swiss financial sector for a century.” Guex believes the banks will get rid of all American clients who engage in tax fraud, but asks, “Will they get rid of clients from other countries—in particular, the Brazilians, Chinese, Indonesians, Africans? That’s another question.”

Naville agrees that Swiss-based wealth management will pivot towards emerging markets, though he differs in his reasons why. “There are many rich people around the world and there are many countries that are not completely safe,” he says. “In countries that are less politically secure, people will want to have their liquid money in another country than their fixed assets. You cannot move your factory, but you can move your money.” Whichever interpretation is correct, if one is entirely accurate at all, Royal Bank of Canada (Suisse) does seem to be looking farther afield: its annual report notes that in 2012, it acquired “Latin American, Caribbean and African assets” from Royal Bank of Scotland’s Coutts Bank in Switzerland.

The efforts of CIBC and RBC to comply with U.S. tax law serve as a reminder that Canada’s largest banks aren’t just retailers that provide mortgages and business loans: they’re massive multinationals whose operations span the globe. Their efforts to negotiate with the vast data-gathering operations of the U.S. Justice Department on behalf of their branches in Switzerland and the Caribbean underscore not just how far-reaching their businesses have become, but how equally far-reaching the U.S. government’s ambitions have become as well. The global financial services industry is shifting as new regulations like Basel III, Dodd-Frank, and FATCA seek to bring it under control in areas ranging from capital requirements to trading rules to tax compliance, creating massive risks and rewards for clients and businesses as they struggle to adapt to the new terrain. For Douglas Hornung, however, the Justice Department’s Swiss bank crackdown can be summarized much more simply: “It has nothing to do with morality or legality,” he says. “It is merely one huge financial center destroying another.”