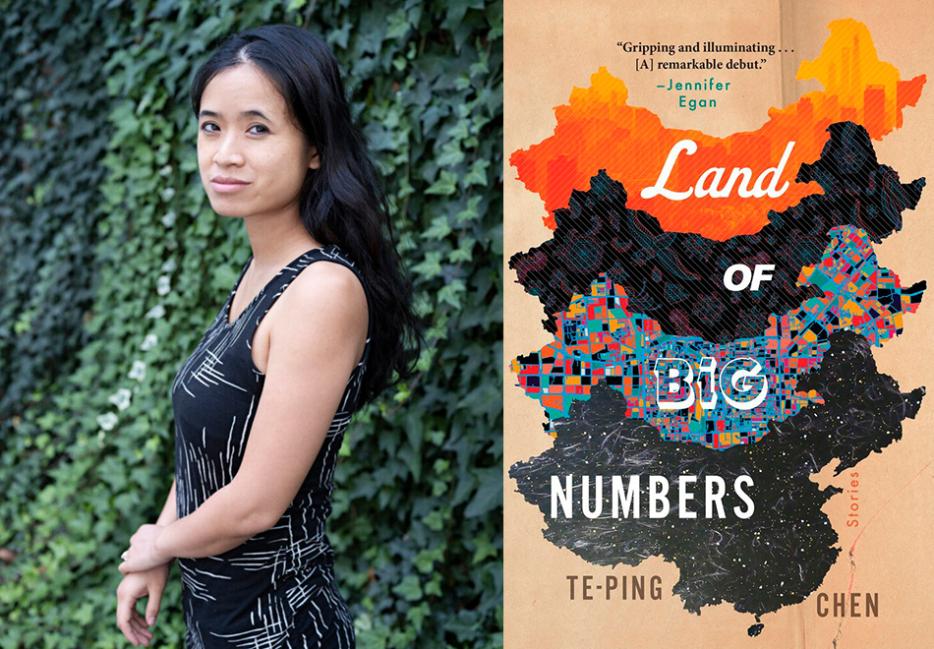

In her deft debut short story collection Land of Big Numbers (Mariner), Te-Ping Chen conveys a variety of tensions: between an individual and her community, a community and the state, an individual and the state; between siblings with different pathways in life, children and their parents, the fantasy of social and economic mobility and its harsher reality.

Chen, who spent years living in Beijing, China, most recently as a journalist for the Wall Street Journal, captures these tensions through the particulars of character and setting in stories that mostly take place in mainland China, with a few set in the United States. Many of the stories are realistic (in one, a woman mourns the death of her husband by trying to get to know his family, where he came from; in another, a pair of twins find their lives diverging as they use online communities in vastly different ways), with a few taking a more surreal or fabulist turn (another story is about a new fruit whose flavor calls forth evocative memories and experiences, tailored to each individual who consumes it), but each is fully imagined, its images precise: a woman is described as having “very ordinary hands, […] a little plump, like sugar cookies”; a young man imagines himself learning a new language, “opening up his mouth like a baby bird learning how to sing.”

Writers smarter than I have written and spoken about the fallacy of stories being universal, and Chen’s certainly are not: they speak to particular places and cultures, class relations, and generational divides. Yet at the same time, they illuminate and trouble the relationship between state violence, community responsibility, and individual morality in ways that are relevant to people in so many nations. To some extent, people everywhere are always relating to the state or nation they live in. In reading these stories, however, I was reminded how many Western nations, and the US in particular, use the narrative of pure individualism as a way to obscure or leave unacknowledged the ties between the individual and the state. Chen’s stories often allude to state violence that is, in some way, always taking place out of the corner of a story’s eye. This doesn’t negate all the specific, individual, day-to-day realms in which the individual characters exist—it’s part of them. In “Hotline Girl,” for instance, there is a sudden, surprising reference to an unmarked government van carrying arrested protesters; in “New Fruit,” a farm is rumored to have been taken over by the government; and in “Field Notes on a Marriage,” a lone, haunting house in the middle of a landfill conveys a quiet, stubborn resistance.

Over email, I spoke to Te-Ping Chen about language, storytelling, community, place, and the nuggets of truth behind some of the more fantastical elements of her pieces.

Ilana Masad: I’m always fascinated by stories that manage to convey in English a life that takes place in another language, in this case Mandarin. I imagine that even if you didn’t grow up speaking Mandarin you would have had to speak it at least proficiently if not fully fluently for your work as a correspondent for the Wall Street Journal. What is it like, writing in English about lives that are lived in another language?

Te-Ping Chen: Growing up, we spoke English at home. I did attend bilingual Mandarin-English school when I was young, and then attended Saturday school for years, which I loathed, and eventually gave up on. But I started studying the language in college again, and then really learned it properly after living in the country, first in 2006 for a semester as an undergraduate, and then in successive stints, including as a journalist with the Wall Street Journal.

By the time I wrote the book, I’d spent years already working in the language and translating interviews and such for the newspaper, and so it was a fairly comfortable muscle. I did end up keeping certain Chinese words in the text here and there, in places where it felt like the sound of the word was important—that it would lose something if it were completely lost—or in places where it felt too artificial or stilted to translate. There were also lines here or there where I’d tried to translate dialogue or a term but it didn’t sound as natural in English, and needed finessing, and editors were helpful in pointing those places out.

Some of the stories in Land of Big Numbers include details that to some readers might blur the boundary between realism and fabulism. For instance, I learned from your publicity material that funeral strippers were one of those stranger-than-fiction details you just had to include, but couldn’t find any info on the government Fitbit-like lanyards in “Hotline Girl.” How did you balance what seemed surreal to you about China with the fabulist or magical-realist elements in these stories? Did your editors ask you to clarify things for a non-Chinese audience?

It’s curious—as you note, some of the details that are taken from real life are the ones that sound the most made up! But yes, funeral strippers are a real phenomenon, as are noodle-slicing robots. The premise of that story [in which both these elements appear], “Flying Machine,” and its central character—a farmer who tries building his own airplane—also takes its inspiration from actual headlines. Over the years that I was living in China, I kept reading so many iterations of that story popping up in local media, about these incredible farmer inventors in the countryside—usually short, unsatisfying dispatches. I was always so curious about what lay behind those stories, so wound up trying to write one.

“Hotline Girl,” [on the other hand, is] a dystopian story of an alternate China, but one that does contain elements that would be deeply familiar to many residents, including themes like surveillance. The "government fitbit" lanyards are made up, though I did have something specific from my own life in mind when writing that detail, namely these badges we had to wear when attending the convening of the National People’s Congress and CPPCC in Beijing, the government’s main political gathering, which occurs every spring. When you walked through security gates, sensors would automatically scan the badge around your neck, and a large nearby screen would flash your name and photo and identify who you were, whether you were a government official or a local or foreign reporter or what have you, and those images were all color-coded by your status, and I was picturing those when writing.

In the end, I didn’t encounter many moments where editors asked me to make things more explicable to a non-Chinese audience. The only one I can think of is a small word choice at the end of “Hotline Girl,” when the reader catches a glimpse of protesters who’ve been rounded up in an unmarked government van. Originally I’d described those protesters more obliquely, because it felt so obvious to me, who they were and how they were being dealt with—in the years I was in Beijing, it was a common enough phenomenon.

To be honest, I didn’t think much about audience or what they did or didn’t know, because I was really writing these stories for myself—and I was so consumed with those questions in my day job as a journalist, it was liberating to get to write without some of those questions percolating in my head.

One of the themes that ties these stories together is the balance of individual and community life. How consciously did you bring in the way that individuals interact with community and vice versa, and how did you balance them?

As humans, we’re always watching other people and aware of others watching us. Our attempts to try and make identity for ourselves are so inextricably bound up in community, and so it didn’t really feel possible to divorce the two. And in many stories in Land of Big Numbers, that’s where the tension arises. Community can be a source of comfort, and we see that in stories like “Gubeikou Spirit,” in which a group of subway commuters get trapped underground for months and end up forming this resilient sort of society among themselves. But that sense of solidarity can also be oppressive, enmeshing and entrapping people and—as we see in that same story—making it harder for the group to escape.

Additionally, these stories all include—either subtly or overtly—the ways that individuals and communities are in a constant conversation with the state. Why did it feel important or true to you to write about state violence in some way? And were you at all thinking about parallels elsewhere as you were writing?

In China, you always have an awareness of the state, even if it’s not in the foreground. You know it’s there, invisibly setting the terms of what’s permissible and what is not—in overt ways, like propaganda banners, but in many more subtle ways too. For those who get in its way, the consequences can be state force and state brutality, but for most people, that isn’t the lived experience, and any such implied threat hovers very much at the edge of the picture. I was trying to capture some of that feeling in these stories, when the day-to-day life can feel so bright, jazzy, and empowered in all kinds of consumerist ways, but with that sense of menace also in the background, and the knowledge that if you step out of line, all this could be snatched away from you and your loved ones. I wanted that discordance to be present, but at the margins—something that if anything, most characters view matter-of-factly and take very much for granted.

I wasn’t thinking explicitly of the U.S. during most of the writing process, but many readers have said they do see resonances, and of course, China is far from the only place marked by that kind of state violence, which at once is so far-reaching in its effects and yet also can be difficult for most people to see.

From a craft perspective, how did you balance the state’s presence in the margins with the weight of what each story was about?

It really depended on the material. In “Lulu,” for example, the title character is grappling very directly with the state, but in others, as in “Flying Machine,” it’s more of a footnote in the character’s broader personal journey.

As a journalist who spent many years consuming Chinese state media, I also had fun gently satirizing such outlets, including in stories like “Gubeikou Spirit,” in which you see state broadcasters working so hard to celebrate these trapped commuters and create this ersatz sense of heroism, which ultimately transforms the group’s understanding of themselves. Power isn’t necessarily a blunt-force instrument, and I was trying to evoke that in these stories, too.

“On the Street Where You Live” is such a wonderfully uncomfortable story. Narrated from an American jail or prison, it also deals in a particular aspect of consumerism—the narrator designed a hit ride for theme parks. It struck me that this story gets at very parallel aspects of what you mentioned above—consumerism and violence existing side by side. There are other themes to the story as well of course (unrequited love, masculinity and its potential for violence), but I wondered if this story was a kind of inversion of the dynamic in other stories, in that here it’s an individual enacting violence rather than the state?

Oh, that’s so interesting! It wasn’t a deliberate one, but I love this observation, and there absolutely is a mingling of both consumerism and violence in this story. When I was writing the main character, I was thinking most specifically of his identity as someone who’s cosmopolitan and rootless, who tries to decode the world around him in such flawed, distorted ways. And how he—like all of us!—so desperately craves connection and is seeking it through these consumerist forms, but not finding it. In some ways I see it as a story about idealism and its dangers, too, and how the ways we put things on pedestals can ultimately betray us.

Class divides play a big role in many of the stories, as do generational divides. In “Land of Big Numbers,” the title story, both of these come to bear, as the main character, Zhu Feng, is of the generation born a few years after the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, while his parents lived through them when they were probably around his age or a little older. In addition to this knowledge gap, there is also a class gap between Zhu Feng and his childhood best friend whose father became rich. Zhu Feng looks down on “the shabbiness of his parents’ lives, their shuffling steps, the curtailed hopes that seemed to express nothing more than a desire to chide bao, chuan de nuan—to be full in the belly, to be warmly clothed,” which made me think about how much that is, really, to be full in the belly and warmly clothed, and whether that too was a generational factor for this young man who also might not have had the specter of famine in his direct past.

Yes! On the one level, they’re such simple desires. And yet also hard-fought and hard-won for his parents’ generation, not something to be taken for granted.

A friend of mine used to say that traveling in China was the closest you could get in some ways to time travel. You’d start in a city like Beijing or Shanghai—cities that in many ways feel like they’re constantly teetering on the precipice of the future—but could get on a train and in a matter of hours end up in a third-tier city that looked like it was stuck in the 1980s, or travel farther still and arrive in a village that looked like it hadn’t changed for half a century. So much of the experience of living in China was that sense of having so many experiences and histories and aspirations all pressed up in close proximity to each other, and sometimes—as in the case of the title story—in just one family.

There are knowledge gaps, too, but I think of those in many ways as gaps in experience. For example, the father in that story is very much aware of the power of the stock market and the new wealth around him that his son covets, but he tends to perceive the risks more than his son, in part because of the gaps in their experience.

Finally, I wanted to ask about the final story in the collection, “Gubeikou Spirit,” which you mentioned above. It’s a story that feels hugely allegorical and speaks to systems of imprisonment (both literal and metaphorical), to the strength of community on the one hand and to loss of individuality among groupthink on the other, to the desire to do good and help others but also stay safe and comfortable. These are themes that run through many of the stories, really. What about this tension—especially between a person’s need to do good or make change on the one hand, and their instinct and desire to stay safe—speaks to you? Is there a personal struggle for you between these things?

It’s something I’ve wrestled with myself, as I think so many of us do; this question of where your allegiances should lie, to family or to society, risk or security, and as we see in “Lulu,” what does it mean to be a good person, and what’s enough and what is ever enough. As humans, we’re really good at tricking ourselves into thinking we’re doing the right thing, to absolve ourselves of any wrongdoings, either personal or those that surround us. And as in “Gubeikou Spirit,” it’s easy to become comfortable, and to tell yourself a story, and become convinced of the righteousness and inevitability of your position. Living in China, it’s very hard to avoid being confronted by these questions, but they’re ones I’ve thought about for a long time, and think many of us struggle with, no matter your position or country.