The good news is that, in space at least, the Russians and Americans are getting along pretty well. As astronaut Mike Coats tells the Houston Chronicle, “Astronaut to cosmonaut, scientist to scientist, engineer to engineer, we’ve had a wonderful working relationship with the Russians.” It’s the concerns of us mere mortals on the ground, in places such as Ukraine, that are mucking things up.

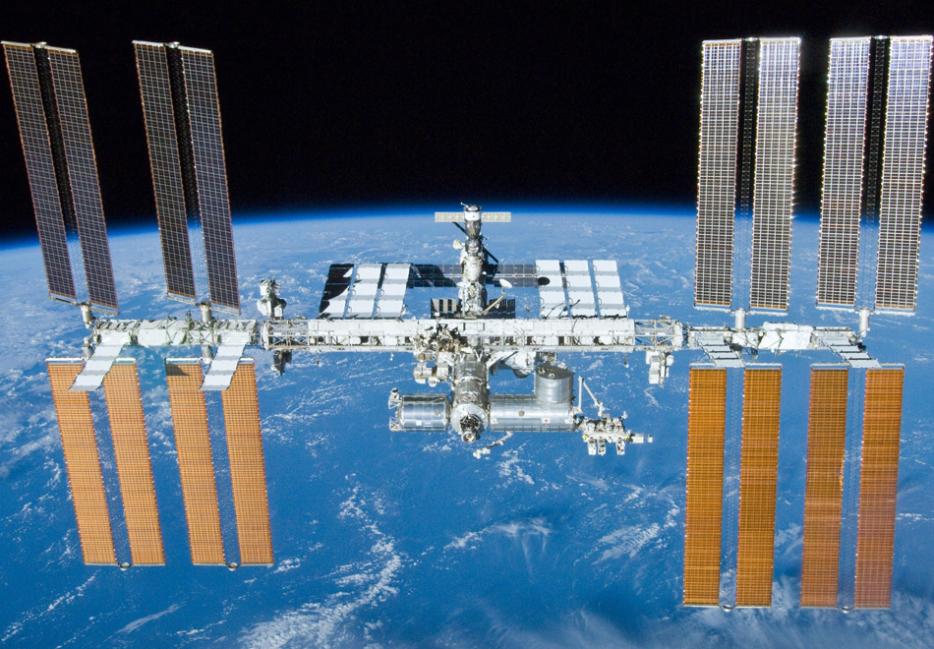

The state of US-Russian relations matters, because the Russians provide the only bus up to the International Space Station: that massive, $150 billion lab built largely with American cash and more than a little Russian competence that’s finally starting to pay off after decades of work—and up to which the Russians are threatening to stop ferrying Americans after 2020.

That may not even end up being the biggest problem, though: Russia is also objecting to US requests to keep the ISS running at all after 2020. (NASA, for its part, has proposed to keep it running until 2024.)

Naturally, it’s possible that relationships will change and Moscow and Washington will get along better by 2020 than they do today. But the only reason this matters at all, in practice, is because the United States doesn’t have its own way to get into space.

With the decision to scuttle the Space Shuttle program, the Bush Administration backed a new rocket to put US astronauts into orbit, but never pushed for the necessary funding. Obama won in 2008, changed course on the rocket technology, and is pushing private companies such as SpaceX to develop commercial flights to the ISS, on contract to NASA. SpaceX is currently planning a crewed mission for 2017, giving the Americans plenty of time, in theory, to get a non-Russian ride.

There are, however, other jobs only the Russians do at the moment—such as periodically boosting the ISS’ orbit so it doesn’t fall earthward like as if it were homesick—so either mending fences or building American alternatives is suddenly very much on the to-do list.

The US is also, nominally, building its own heavy-lift rocket that should, eventually, put them on the path to a crewed Mars mission. Assuming the Space Launch System program doesn’t itself become a victim of politics, that is.

It’s all a bit of a mess; what’s missing is some kind of animating consensus. In NASA’s heyday, things got messy too (and some astronauts died), but nothing was allowed to distract from the goal of putting men on the moon and returning them safely to Earth. The agency—the country—that met Kennedy’s goal in less than a decade now thinks the height of ambition is aiming for Mars sometime in the 2030s.

Not only does the US not have anything like that consensus today, it’s not even clear what could possibly replace it as an impetus to taking manned space exploration seriously. Science? A) We don’t really care about science, and B) our robotic probes are getting better a lot faster than people are. Crewed missions can do a lot of important science, too, but they’re absurdly expensive relative to machines.

So, less noble motives? Will Americans really care if Russia, or China, wants to put boots on Martian ground before the US? To what end?

The other possibility is that we skip the whole Apollo-style NASA space program. If the point is to put people in space for people’s sake, maybe Elon Musk and the nutters at Mars One have it right, and we should instead see who’s willing to just go live there permanently. It might even be relatively economical, considering that much of the expense in these missions is the cost of bringing people back home. And there’s something oddly fitting in 2014 about the idea of the next chapter in space exploration being a reality TV plot.

And hey, if it works, they’ll have done something that not even the most powerful governments in the world have managed to do in 50 years: make space travel pay for itself.