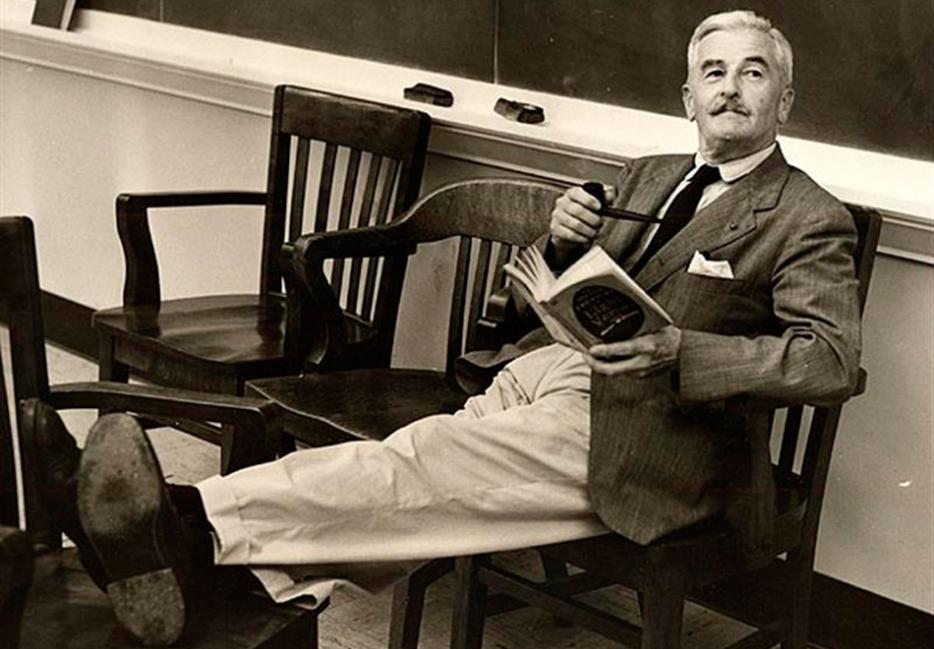

A US court recently decided that William Faulkner’s estate was not owed anything by Woody Allen, who paraphrased a line from one of Faulkner’s novels in his 2011 film, Midnight in Paris. Stap my vitals. I shudder to think of the future of a race where the seeds of such avarice have been sown.

Faulkner’s line, from his book Requiem for a Nun, is “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Woody Allen wrote, “The past is not dead. Actually, it’s not even past.” Pretty close. He did, however, follow it up with this one: “You know who said that? Faulkner, and he was right. I met him too. I ran into him at a dinner party.” That, I believe, would be attribution.

Judge Michael P. Mills of the United States District Court, Northern District of Mississippi, seemed to agree, treating the issue with all the seriousness it deserved. In the opening lines of his decision, Mills replied, “The court has viewed Woody Allen’s movie, Midnight in Paris, read the book, Requiem for a Nun, and is thankful that the parties did not ask the court to compare The Sound and the Fury with Sharknado.”

You might think the absurdity of this case is patent, but it’s par for the course in the Havershamian realm of literary estates, often populated by accidentally well-connected people with little to show for the time they’ve spent on the planet except their “moral rights” over the words of their elders and betters.

It’s more than enough to make me think the whole concept of literary estates should be scrapped.

Consider the case of James Joyce’s estate, which, represented by his only surviving descendant, Stephen Joyce, was even more ridiculous than Faulkner’s. In 2004, the centenary of Bloomsday, celebrated annually all over the world on June 16 as the day on which Ulysses was set, the living Joyce threatened to sue the Irish government if there were any readings from his grandfather’s books. Cowed—Joyce’s lawsuits were often successful—they cancelled their events. According to an infuriating story in the New Yorker from 2006, he even once told a performance artist named Adam Harvey, who had memorized a section of Finnegan’s Wake in the hopes of reciting it, that he had probably “already infringed” on his copyright.

The gibbous shitbox lives—or lived, at least, at the time of the New Yorker piece—in what’s described as the Martha’s Vineyard of France, his entire life financed by the work of a man who died before his grandson’s ninth birthday. “I am a Joyce,” the New Yorker quotes him as regularly declaring, “not a Joycean, and there is more than a nuance to that fact.” He’s a tiny, tiny thing, ever flying in the spring, round and round a ringaring. Long ago his grandfather was a king, and now he does this kind of thing, on the wing, on the wing! Bing! (As Joyce, the worthwhile one, might have described his odious offspring.)

On December 31, 2011, a tweet with a link to an Irish Times article on the subject was sent out that read, quite charmingly, “Fuck you Stephen Joyce. EU copyright on James Joyce’s works ends at midnight.” There’s some dispute about the copyright of Ulysses in the US—it may be in the public domain, or it may be copyrighted until January 1, 2030 and/or January 1, 1957. But in Canada, I’m happy to say, it’s all free, and we can speak here of ringarings and bends of bays without fear.

I dwell on Joyce and his grandchild because it’s as good an example as there exists of the senselessness of this approach to literary copyright. While a writer is alive, I full-throatedly support her right to collect all monies possible related to the work she’s done. This money can be used to pay for educations, houses, put into annuities and otherwise invested to help to benefit whatever survivors the writer might leave behind. But then there’s this: If people like Stephen Joyce—who apparently insists on being called Stephen James Joyce—were alive when his grandfather was working up the creative sweat his descendant is now soaking in, Ulysses (and probably Finnegan’s Wake, but who really knows?) could never have been written.

There has never been so great a pastiche of others’ efforts worked into so magisterial a work of synthesis as Ulysses. Some of it is taken from work that, at the time, was well out of even present-day definitions of copyright’s grasp, like The Odyssey or Tom Jones. But he openly acknowledged using the words or style of more contemporary writers, like Walter Pater and Cardinal Newman, both of whom died in the 1890s, just a couple of decades earlier. There has, in fact, been so much scholarly work done on Ulysses that, for instance, one can say with authority that chapter 14 alone boasts 1,000 literary references, quotations, style riffs, and other borrowings and stealings.

But what Joyce did prodigiously, other writers—all other writers—do as a matter of course. Literature is born of other literature. Books beget books. Shakespeare himself only rarely came up with original story ideas.

There is no literary reason to maintain copyright after the creator’s death. Paintings are objects and they have owners, and the owners of these objects have rights. But books are mass-produced; there is no object in question for the descendant to own. There is a case to be made that a writer owns her words in some respect, but for literature to be literature, it must cascade, well up, overflow—there must be confluences and admixtures. Giving husbands and wives and children and nephews the right to dam any of that up does no one any good other than the folks raking in the cash and puffing themselves up with Cartmanesque authority.

But literary executions like this can be damaging and wrong even when they’re not being handled by fools. Valerie Eliot, T.S.’s widow who just died this year, was by most accounts an intelligent and conscientious executor. But because her husband had told her he didn’t want any biographies written about him after he died, she did everything in her power—and as keeper of his letters and personal papers, her power was considerable—to prevent biographies from being written and, when they were, prevent their writers from having access to things that might let them write a truer portrait. Valerie loved Tom, so of course she’d want to respect his wishes. But no biographies of one of the giants of 20th-century literature? Nonsense. Writers often make poor custodians of their own work; literary executors tend to just extend the damage.

Faulkner once wrote, “This ain’t Jackson’s leg nor Stuart’s nor Rafe’s nor Lee’s. It’s mine. I done started it; I reckon I can finish cutting it off any way I want to.” He may have had a point, as far as legs are concerned. But there’s no room for “mine” in the works that make us who we are, as people and a culture.