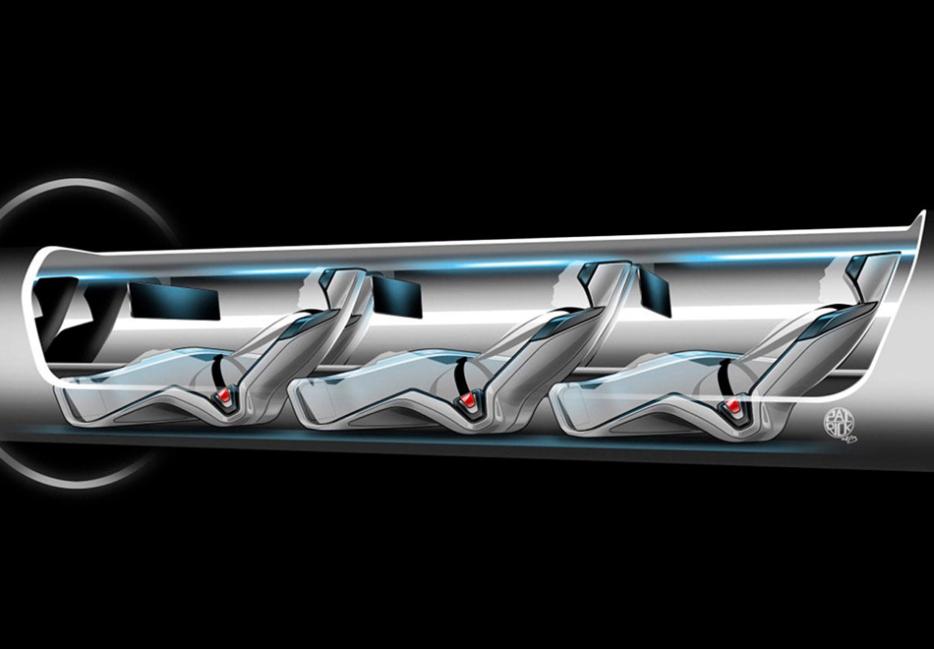

Three intriguing transportation technologies have floated past in the fog of headlines this month. First, South Korea unveiled an electric bus that is powered by a magnetic coil buried in the road. Second, nominal plans for a Jetsons-looking pod transit system for Tel Aviv apparently got closer to reality. And of course, on Monday, Elon Musk unveiled his notion of the Hyperloop.

I’ve listed these ideas both in ascending order of awesomeness and descending order of likelihood that you’ll ever actually ride one. That is, in 2050, I suspect a great many of us could be riding on electrically charged buses in areas where people are too precious to allow overhead wires (the trolleybus is a thing, look it up), but I suspect almost nobody will be riding elevated podcars on overhead rails or, alas, lining up to be shot at intercontinental speeds through an almost-airless, windowless coffin tube.

Which is a shame, because the science fiction fan in me really, really wants to fall in love with the Hyperloop, and the Canadian in me wants to believe in a technology that can finally put a stake through the heart of our oldest enemy, distance. Alas, people much smarter than I are skeptical about the proposal and annoyed by the fact that they’ll spend the next few years having to explain at dinner parties why, no, Elon Musk didn’t make trains obsolete.

The short version is that what Musk is proposing is actually fantastically difficult and almost certainly costlier than he projects, would carry fewer people than most successful high-speed trains do, and assumes in all this he can avoid the kind of politics that have gummed up the legitimately disappointing California HSR project. It would be one thing if, like his electric car and rocket company, Musk was committing his own money. Thus far, he notably is not, on a plan that is by his own admission not ready for prime time.

The more basic fault with the Hyperloop is the effort to literally reinvent the wheel: Understandable when it comes to frustrated billionaires wondering why they can’t be in Los Angeles right now, but not a substitute for good transportation engineering. The disappointing-to-fanboys reality is that, in 2050, we are almost certainly going to recognize all of the major transportation technologies.

That’s not to say that transportation technology won’t change in the future, possibly more than we think. The effort from major automakers to build self-driving cars has an obvious application in transit where the most expensive part of a bus is the driver. Admittedly, “superbus” doesn’t have quite the same ring as “Hyperloop.” But unlike the Hyperloop, self-driving road vehicles will, if they work at all, plug into the existing transportation network without having to rebuild the entire thing from the ground up.

And forget pod transit along the lines of what’s being proposed in Tel Aviv: It may not be sexy, but a self-driving car will do the same job. The problem we need to solve with our roads isn’t that we desperately need some new form of technology, it’s that the ones we’ve been using have been so wildly successful that there are too many people on them. The most obvious answer—charging more for use of the roads—offends our sense of the car-ordered universe, but we’ll have to get over that someday.

I’d be lying if I said part of me didn’t want to see Musk or other futurist sirens prove me wrong. That part of me—the one that wishes I’d grown up with the open technological horizons of the “Our Friend the Atom” era—would be cheered by the thought of a new way for humanity to master the physical world. But the future has changed, and it’s not all bad. There are even flying cars, if you know where to look.