In his essay “Theses on Monsters,” the cryptozoologically inclined novelist China Miéville wrote: “Epochs throw up the monsters they need. History can be written of monsters, and in them. We experience the conjunctions of certain werewolves and crisis-gnawed feudalism, of Cthulhu and rupturing modernity, of Frankenstein’s and Moreau’s made things and a variably troubled Enlightenment, of vampires and tediously everything…” And yet, too slippery or slimy to signify consistently, “a thing so evasive of categories provokes—and surrenders to—ravenous desire for specificity, for an itemization of its impossible body, for a genealogy, for an illustration.” Gotta catch ‘em all. If the creatures populating Paul Pope’s new book Battling Boy document anything, it’s the history of comics itself, a pulp corpus made up of razored scales and sooty tendrils.

Pope, who resembles those rock stars of indeterminate age (he’s 43), developed his long, lush brushstrokes during a mid-’90s apprenticeship at the manga publisher Kodansha. Most of what he drew in Japan remains unpublished, but it’s hard to imagine the kinetic vim of his subsequent work without that immersion. Pope’s panels have the composition of blurred afterimages. Few other cartoonists make physics in motion look so graceful: wispy contrails, burst plasma, lightning springing from the aether. You can find more concrete subjects recurring between books such as Heavy Liquid and 100%—fantastical paranoia in the strung-out style of Philip K. Dick, stylish kids tangling around each other—but I always recognize Pope’s comics from those ribbons of energy first. His drafting pace isn’t as rapid. When I profiled the artist in 2007, around the time he published Batman: Year 100, he mentioned something called Battling Boy, “a story of a young god or a young superhero, who’s on sabbatical from Mount Olympus, and his job is to clean up this giant city, which is overrun with monsters…”

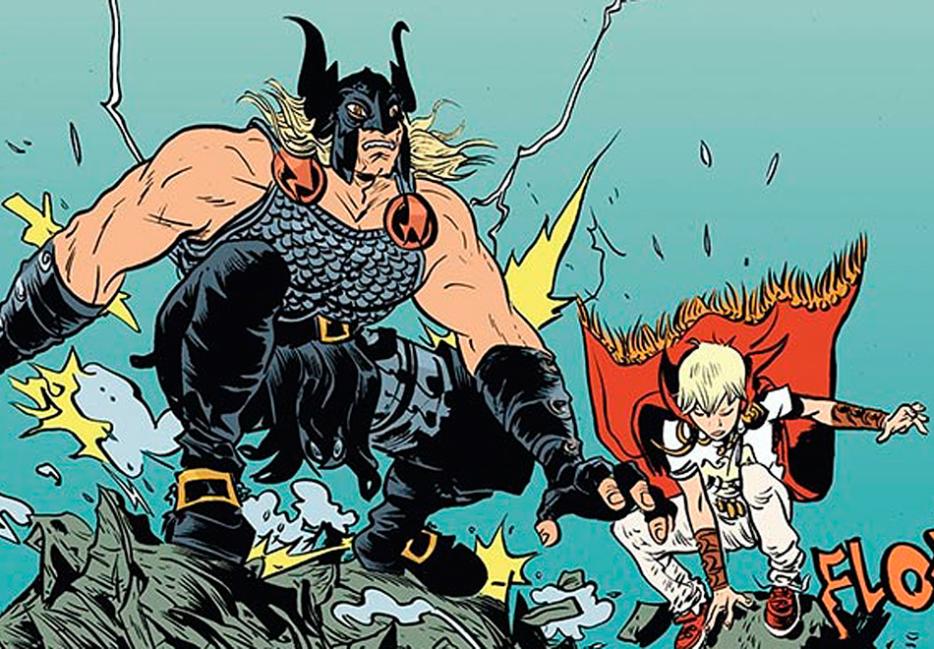

Batman: Year 100 imagines the title character as a theatrical Expressionist vampire, undermining the surveillance state in a dystopia of the imminent future. Pope often adopts conventional adventure narratives while toying with their details. Battling Boy’s Haggard West, a science hero and blustering vigilante who tries to protect Arcopolis from its monsters, gets himself vaporized after 20 pages. (It’s strangely reminiscent of Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen story Heart of Ice, where the historical-fictional boy adventurer Tom Swift appears as a confidently bigoted coward. 2013: the year comics subverted semi-obscure pulp characters.) Even the little godling’s arrival in besieged Arcopolis from a higher plane isn’t as purely altruistic as it might appear; his Thor-looking father, who says things like “What news!? I’m famished and I could drink a river for this thirst!,” frames the mission as a ludicrous initiation ritual, in the manner of young British aristocrats and fox hunts. Tapping the kid’s enchanted gauntlets, he advises: if some hideous creature is about to devour you, call me.

About those monsters: they span the bestiary, from humanoid to animalistic, nightmarish or kinda-cute. In keeping with the “as above, so below” structure, which Pope emphasizes using the comics equivalent of match cuts, they have their own realm too, subterranean catacombs where your bartender garnishes a paint-thinner cocktail with uranium gumballs. There’s spidery, plump-fanged merchants, a truculent anthropomorphic hyena in the funny-animals tradition, and the imposingly broad Dinosaurus, whose horns stretch beyond the horizon line. At this point in the series, the primary antagonists seem to be a pack of rag-wrapped, child-kidnapping ghouls, but the first volume’s star is a massive pest called the Humbaba, found snacking on entire cars. (Battling Boy manages to kick its teeth out from the inside, a move I don’t think I’ve seen before.) With its floppy bat ears and narrowed crescent eyes, the Humbaba reminded me of Maurice Sendak’s Wild Things, given over to id and appetites entirely.

Other conjunctions emerge. The action sequences’ spatial dimensions evoke the widescreen vistas of shonen manga, while the home of the gods, leaving a galaxy-sized wake as it blasts through space, is gleefully modeled after the most cosmic stories by Jack Kirby (Fourth World, The Eternals), a longtime Pope fixation. Battling Boy comes equipped with a zodiac’s worth of animal T-shirts, each bestowing its own powers and weaknesses, which almost seems like an excuse to draw painterly Bill Watterson portraits of the orangutan and the pterodactyl and the wolf. (Some of them don’t correspond to abilities so much as states of mind; the fox counsels its wearer to trick Dad into bailing him out, and then the elephant states, in not quite so few words, read your damn textbook.) But there are limits to taxonomy. One of Miéville’s monstrous theses argues: “Any bugbear that can be completely parsed was never a monster, but some rubber-mask-wearing Scooby-Doo villain, a semiotic banality in fatuous disguise. It is a solution without a problem.” The moments of verisimilitude in Battling Boy—the hero’s adolescent monosyllables, or the incredulous annoyance Haggard West’s daughter displays while rescuing him—are just ballast for the sublime. Cartooning history pervades this book like the archetypes of a collective unconscious, never wholly knowable, faces in the night.