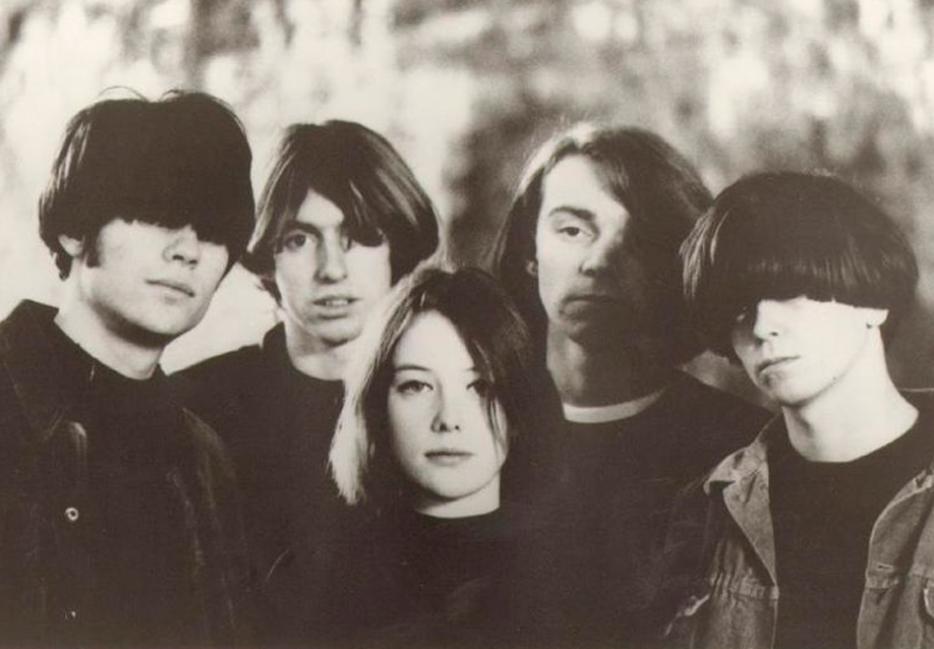

Slowdive, a band I’m sure is very good but that I care not a whit about because I am one of those lost and lonely few in 2014 who gives zero damns about shoegaze, is reuniting. You won’t see too much complaining about this online, because a) music writers love shoegaze like it was the dove of Christ newly sprung from their chests, and b) Slowdive might come to your town! And that’s fine: kneejerk dismissal is always a drag, especially when applied in the wholly arbitrary fashion typical of critical groupthink. This quiet acceptance is rare, though. Whether it’s The Eagles or The Police or Blink-182 or even a band that was good at some point, the overarching belief remains: reunions are the product of a morally corrupt nostalgia machine that crushes and gnashes our innocence like the cud of a dystopian mechanized bull. Or something like that.

But what are the specific arguments against bands reuniting, really? The most immediate one is that, except in very rare instances (see: The Pixes … at first, anyway), the band reuniting will not be, objectively speaking, as good as they were during the original run. It’s rock and roll, theoretically a young person’s game, and the reunited band will be much closer to the ends of their lives than when they started. Plus, unless they’re writing new material that somehow encompasses the wisdom that comes with the nagging terror of looming death, they’ll be performing the same callow bullshit they started with, pantomiming youth while looking like soil erosion. This phenomenon is—and I say this in the interest of maintaining the all-important sense of objectivity necessary for discussing arrested developed halfwits hopping around on stage wearing hip-slung basses—pretty bad.

So: seeing the reunited band will not be as good as seeing them in their prime. Compounding that sad fact, let’s take a look at you (read: me), shall we? You (I), my friend, look like shit, and the feelings you get while listening to Nevermind now can’t even begin to approximate the feelings you had listening to, really, anything when you were still young, dumb, and full of high hopes. Even if the reunited band is, by some small miracle, as energized as they were when they were still putting out non-limited run tapes, you (I) will hardly be able to emotionally hold up your end of the bargain.

(And if you are still young, what the hell are you doing here? Don’t you have bands your own age to play with? Theory: young people ought to only follow bands made up of members roughly five years older than they are. Not only do you not want to live inside an entire other generation’s decaying dream—you’ll get your chance, kid—but, who knows, you may get the opportunity to fuck someone in a band you love, and wouldn’t it better if it weren’t completely awful and accompanied by noises that a reasonable person shouldn’t expect to hear from their body until well into their thirties? Seriously, boys and girls who bang band members, stay off the revival circuit. The keyboard player, despite his or her protestations, is definitely still married.)

Another scenario that sets off the “don’t do it” alarm bells: if one or more of the original members is dead, successful outside the band, or refuses to take part due to either artistic or integrity issues. Crass, Alice In Chains, The Replacements, Bad Company (who, when I saw them, was just the drummer and his daughter), The Temptations Mach 57—none of these is really, judging by the lineup card, a reunion. One could argue, then, that as they’re not technically reunions, they can’t be judged as such, either. Sound like hedging? Sure does. Let’s put this in the “pretty solid” column.

Possibly the most common argument against a band reuniting is that it’s a cash-grab, and musicians getting back together solely for the filthy lucre can seem despicable on the face of it. But, as someone who was in a band that, I can assure you, would reunite for store credit and half a tuna melt, I am sympathetic to both this reasoning and the denunciation of such. The idea of band members reuniting with people they loathe to perform songs that are emotionally foreign lands to them now—even, in the case of track-suits-and-short-hair-era Sisters of Mercy, playing for an audience they openly hold in contempt—just to put a payment down on those Kate and Allie Real Dolls they had their eye on or make a dent in their overdue child-support is pretty dispiriting. I’m a broken record about art being “just a job,” but art being a job doesn’t automatically rule out any of its higher spiritual aspirations. (I would also, for the record, go see the reunited Sisters of Mercy under any circumstances, and I would gladly hold Andrew Eldritch’s sword cane if he asked. That’s probably not a euphemism.)

Then there’s the “this band isn’t important enough to reunite” argument. See, there’s this thing at the intersection between the worst music nerds and the worst comic book nerds (and, nerds, I say this as a pretty bad representation of both) called “canon.” Canon is the art or narrative that “really matters,” as determined by people who wouldn’t know true meaningfulness if it were spelled out in the liner notes of Exile on Main Street (a not-particularly-interesting canon album, as determined by people who have either never tried heroin or won’t shut up about it). Within this rarefied stratosphere, some bands don’t matter. They didn’t sell enough copies, or they sold far too many; either way, they haven’t been immortalized in even a single oral history. Why the fuck are they getting back together? This gets applied to a lot of ‘90s hardcore/emo/screamo/wearing-shorts-on-stage acts—many of which are reuniting, and many of which were definitely not big the first time around. It’s entirely reasonable that genres of music by and for those who fancy themselves misanthropes would instill a distrust in anything that could be construed as a contrived rehash of a glory that never truly existed. But all the “-cores” are highly dependent on nostalgia from the get-go—nostalgia for youth, innocence, that golden age from a week ago when there was no backstabbing and the “scene” was fun and true. So hardcore reunions should be seen as the logical conclusion of a worldview rather than a betrayal. And even if it is a betrayal, what’s the problem? Hardcore kids love betrayal. So get back together and be blessed, Wide Awake. And fuck a canon. That shit’s for dads and priests.

With punk bands—whether they be (ugh) Sex Pistols, (ugh-er) Black Flag, or (ugh-est) Refused—it’s a bit more complicated. Taking The Who’s hogwash of wanting to die before getting old into the realm of the literal, so much of punk’s lyrical content is about dying young that it can be comical when sung by someone who categorically failed to accomplish what is, let’s be real, a pretty easy task. Also, let me clarify here: in any of these cases, don’t interpret my defense of any band getting back together as meaning that you have to take them seriously. Nobody has the god-given right to escape ridicule, musicians least of all. Existing in the airy-fairy realm of creativity sometimes means that you have to tolerate a world guffawing in your mascaraed face; all things considered, it’s actually a pretty decent trade-off. So if a punk band can handle that, wipe the spittle off, and play the one chord that propelled them to this point of wonder in the first place, mazel tov. After all, those lyrics about being dead will eventually be true, and in this game of inches, eventual truth is an acceptable centimeter.

Possibly the most offensive reason for being anti-reunion, though, is because of how it affects the listener’s precious memories—their youth. God, we love our youth so much we should marry it and have little youth babies made up entirely of every stupid thing we said between the ages of 13 and 27, a Cthulhic monstrosity we keep in the walls, constantly tapping out Dave Grohl’s most beloved drum fills. So you hate bands reuniting because of what it does to your memories, how it affects your tender if complicated feelings about the past? What about those of us less inclined to give a damn about our lives at 16—those of us who don’t much care about our past or your past except as pure history or an (in retrospect) indicator of the present? Are we supposed to just stand around holding our breath while you collect yourself? Your memories are just the synapses of your brain firing off trying to tell you that you married the wrong person. Too late, you time machine-less jerk. Start worshipping at the altar of adulthood and let the Boomtown Rats get back together.

(For purposes of rebuttal, my fiancée points out that if I hadn’t consumed four fluid ounces of Robitussin every day between the ages of 13 and 27, maybe I’d actually have some memories and, perhaps, even be inclined to romanticize them. Fair enough, pretty lady.)

Of course, all these condemnations spring from a belief that rock music itself loves to perpetuate: that’s there’s something unique about rock and roll that separates it from other artistic endeavors, that it’s the product of some fiery spark of creativity that is only for the post-pubescent and wild and free. After all, we don’t cry about actors or painters working well past their perceived primes, right? This is, of course, horseshit. Rock is country is jazz is hip-hop is house music, and to believe otherwise is to make a false idol of the pins on your jacket. And anyway, liberating yourself from that self-congratulatory mythology also allows you to both attend and play in an Archers of Loaf reunion without crying all over your too-tight argyle. I’m not necessarily advising either of those things, but it’s not really my place to judge. You’re talking to a guy who straight-up prefers a reunited Rorschach to the entire Deathwish Inc. catalogue. If Deadguy got back together, all my reviews of new bands would consist of, “Pretty good. I wonder if they’ll go see Deadguy with me next week.”

Which brings us to the greatest point in favor of bands getting back together, regardless of the emptiness of their reasons for doing so: simply put, what some men or women do with their collective labor is none of your goddamn business. They wrote, performed, and recorded the songs. They can break up, get back together, hand the songs over to the good people at Outback Steakhouse and, really, all other opinions, your and mine alike, are beyond immaterial. You can try to attach a moral component to it, but that’s like attaching a moral component to deejaying vinyl versus off a computer: it may impress your like-minded pals on the Internet, but it makes you a … well, I was going to go with “finger-wagging prick,” but as someone who leans towards trivial motherfuckerdom myself on occasion, that’s a bit ungenerous of me. And I try to be generous. So let’s just say that while you choose to shake your tiny fist at the past and its continuous rude infringement on your glorious present, I’ll still take your other hand in mine, because I know your heart is good. Besides, I got on the list for the Toy Dolls reunion, and you’re all my plus-one.